Excerpt from the final chapter of HEAVY: A Memoir of Wyoming, BMX, Drugs, and Heavy Fucking Music by JJ Anselmi

Excision

The surgeon draws an ellipse on my forearm with black marker, injecting anesthetic at several different points. When my skin is numb, she delicately traces the marker plan with her scalpel. Each cut loosens taut forearm flesh that, throughout the past nine years, has been stretching and regenerating to compensate for over twenty square inches of removed, tattooed skin.

Six inches down from the beginning point, she cuts out the remaining scar tissue, formed during the eight months since I’ve last gone through an excision. A burning sting pulses through my arm.

I see a reflection of gray muscle in the glass cover of the surgical lamp. Small whorls of skin dot a strip of gauze on the surgeon’s tray. Slowly, she works up my forearm, stretching skin and suturing.

While she threads, I remind myself that this scarification process has kept me sober, which, in turn, kept me from dropping out of school. During the next six months, my body will build a protective barrier around this wound, only to be excised after my skin has once again stretched enough for another procedure. Although the surgeon initially told me that I’d be done in two years, it’s been nine since I started, and at least two more years of excisions loom.

***

In September of 2006, a few months after my dad’s drug-addicted and motorcycle-riding friend, Joey Hay, committed suicide, and roughly a year and a half after I drove to Bondurant to kill myself, I stopped drinking and getting high. In addition to my own drug-fueled thoughts about wanting to die, Joey’s death made partying inseparable from suicide in my brain.

About nine months earlier, I’d moved out of Rock Springs and enrolled at Denver Community College, knowing that I had to get out of Wyoming. During the spring semester, I worked at a shitty pizza place, smoked and drank constantly, and half-assed my classes. When I was honest with myself, I knew that, if I was ever going to finish school, I had to get sober.

I tried to quit getting fucked up a few times throughout the summer, but the longest I made it was three weeks. Searching for the rigid stability I was able to find throughout high school and junior high, I’d tell myself that I was meant to be straight edge. I’d rant to my friends about how society revolves around getting fucked up, and how I wanted no part in this.

Then, a few days or a week later, I’d convince myself that I could control my pot smoking and drinking. Most of my favorite musicians smoked and drank constantly, and part of me still believed that I was destined to be a famous drummer. I remember waking up after fucking up my brief stints of sobriety, which happened several times, and feeling empty, erased. In the back of my mind, I knew that I needed something extreme to keep me sober, that I needed to destroy parts of myself in order to create a new sense of self.

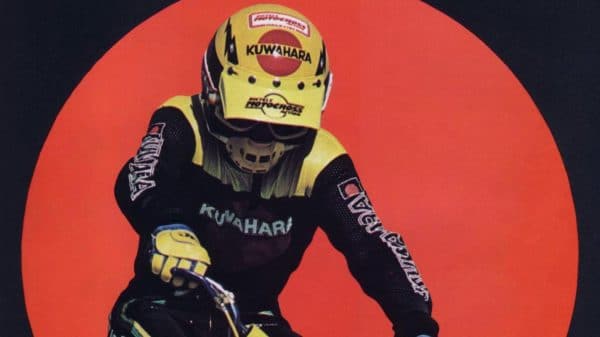

When I was eighteen, I got Tony Iommi’s signature guitar tattooed on the inside of my left wrist, along with the song title and lyric, “Killing Yourself To Live,” wrapping around my wrist. I got three more tattoos engraved into my skin within the next six months: Pantera’s emblem, CFH, on my right wrist; a large skull with sharp teeth and bats pushed through it that Metallica used on merch and posters during their Master Of Puppets tour, which covered my right forearm; and Black Sabbath’s effeminate, fallen angel on my right shoulder.

Two years later, I felt like I needed to erase my tattoos.

I started researching tattoo removal after a month of staying clean—my longest stretch at that point. I found out that laser removal leaves a faint shadow of the original. One technician told me that, in the best-case scenario, a laser could only remove 95% of a tattoo. Other people probably wouldn’t notice the shadows, but I wanted to completely disconnect from my past, not seeing the violence in this ideal. In my case, this violence became physical as well as mental.

I found a plastic surgeon who removed tattoos via excision—a process of cutting out pieces of tattooed flesh and suturing the skin back together. Each excision creates a new scar, which, until the tattoo is gone, the surgeon also cuts out during the procedures. When the process is done, I’ll be left with large, gnarly scars instead of tattoos. The surgeon warned me that, while going through this process, my tattoos would look worse than they originally did, with scars cutting through the black ink.

Looking back, I don’t think anyone could have talked me out of getting my tattoos excised. I’ve always been a hardheaded motherfucker, and, when I decide to do something, there’s usually no turning back. But I did decide to keep the fallen angel on my right shoulder—both because I wanted and had to. I knew Black Sabbath’s music would always be part of who I am, and also that removing this tattoo, which covers several square inches of skin on my shoulder, wouldn’t be possible via excision. If the tattoo was smaller, and in a place on my body that would make it easier to remove, I think I still would have kept it, although I’m also not sure if this is true.

I started to picture myself with scars instead of tattoos, deciding that the scars would represent my return to straight edge.

I had to keep going after the first excision.

During that first procedure, the surgeon cut out “Killing Yourself To Live” from my left wrist, and the center portion of the CFH tattoo from my right. Just before she began, I felt the same uncertainty lodge in my throat that I’d felt before getting my first tattoo. But I told myself that, if I was going to stay sober, I had to go through with this. Reclining in the surgeon’s chair, I stared at the gray tissue beneath my skin before she sutured me back together.

As scar tissue formed on my wrists during the upcoming weeks—red wounds slowly transforming into white skin—I realized how grotesque my arms were going to look until I finished the excision process. After the next session, my tattoos became unintelligible. Scars cut through my ink, and you couldn’t tell what the tattoos were originally of unless you’d seen them before.

I immediately regretted my decision to have my tattoos removed, but, at the same time, I knew that, once the ink was gone, my scars would be beautiful in a weird and fucked up way.

Looking at the jagged scar on my forearm, as well as scars crawling up both of my wrists, I see my mental progression. If I’d never started this process, I’m not sure that I would’ve finished grad school, that I’d ever have become a teacher and writer.

At the same time, this scarification process has fucked me up in ways that I never expected. Getting tattoos of metal bands was a way to conform to a metal head stereotype, but my tattoos also gave me access to a sense of community that I haven’t been able to find again. And they didn’t prevent me from interacting with people. I’d never truly felt socially isolated until I began my scarification.

When I wear short sleeves, the first thing people usually notice about me is the massive scar on my right forearm, which often prompts questions about what happened. I’ve lied a few times, telling people that the scar is from a gnarly wreck on my road bike. I’ve told myself that these instances were the result of people’s rudeness—staring or asking in an insensitive way. But I also know this is only partly true.

Usually though, when someone asks about my scars, I tell them that I’m going through an intense and bizarre tattoo removal process, which leads to questions about why I’m doing this, and what the tattoos were originally. It’s hard to pick up casual conversation after you tell someone that you’re having pieces of yourself surgically removed. When my scars are exposed, I can only find intermittent comfort in social situations, which is worsened by the fact that I won’t allow myself to drink. Even with close friends, I neurotically fold my arms or position myself in ways so they won’t be able to see my scars.

At metal shows, I feel disconnected from other fans in ways I never foresaw. I used to see myself as inhabiting the center of the metal world. Now, I feel like I’m always on the periphery, even when playing shows.

A typical conversation at a metal show:

Me: “Have you heard that new Converge album, dude? It’s so badass.”

Metal dude: “Fuck yeah, man. I love that shit.” The guy has shoulder length hair and tattoos covering his arms. I started talking to him because he’s wearing a shirt of one of my favorite bands.

We feel at ease with each other, bonded by our enthusiasm. But then the guy notices my scars, and I can tell that he suddenly feels uncomfortable. As we keep talking, he glances at my arms. He’s curious but feels like he shouldn’t ask about my scars, not wanting to offend me. I can’t count how many times this scenario has played out.

Routinely getting asked about my scars, as well as the looks of confusion, fascination, and disgust that I get on a daily basis (if I saw someone with massive scars snaking through their tattoos, I’d stare, too) eventually made me feel physically repulsive. It took me four years after I started my scarification to finally get myself to kiss a girl I’d been dating, although I’d had a few opportunities—times when it was more awkward not to kiss a girl. But my self-imposed isolation led me to focus on school, which helped me realize that I’m a writer.

For two to three weeks after an excision, I can’t play the drums. Before I started this process, and ever since I began playing drums, I’d never gone more than a few days without practicing. During that first two-week period of not being able to play, I needed a creative outlet, and I gravitated toward writing, beginning a very early and shitty draft of Heavy. I fell in love with the space writing opened in my brain, which, I think, is the same space I’ve often found through BMX, vandalism, and acts of self-destruction. Throughout the years, writing and school have made me more self-conscious, but I’ve also learned that self-consciousness is a form of misery.

On one level, I’m ashamed of my scars, knowing that they’re products of the same extremist thinking I used to define myself in high school, which, in large part, led to my destructive use of drugs and booze in the first place. My scars are also a different kind of tattoo, symbols I’ll have on my body for the rest of my life.

At the same time, I can’t deny that the need to make my scarification mean something has kept me from getting high or drunk, which has made me more productive. I constantly scold myself for not doing enough, and I can only rarely shut off that critical voice. Without finding meaning in my scars, I’m not sure that I’d want to keep living, even though I also know this meaning is fundamentally fucked up.

Looking at my scars, I see how violent it was to believe that I could become a completely different person. At the same time, I know this scarification process has permanently changed who I am.

Newly sober and just beginning my tattoo removal, I started to view Metallica, Slayer, Pantera, and Sabbath through a more thoughtful lens, which eventually became part of me. Now, I see Black Sabbath as a husk of itself, each member knowing they can get away with half-assed musicianship while still playing packed stadiums. The band’s legacy is undeniable—they fucking invented metal. But, when they play now, the jazz flourish that made the early albums so heavy is gone, even though, if they really wanted to, I think they could be tight again. Throughout the years, I’ve watched countless underground bands that will never make a living on their music, but who refuse to settle for anything less than their best, and I now hold most musicians, including myself, to this standard.

I’ve also come to understand what should’ve been clear about Pantera a long time ago: they’re ignorant rednecks, sporting the Confederate flag on instruments and banners and also printing it on their merch. Throughout junior high and high school, I didn’t think about how fucked up this actually is. I bought into the idea that the band was just proud of their Southern roots, that flying the rebel flag isn’t a racist act. But, after living in a mostly-black neighborhood in Denver and taking a few eye-opening sociology classes about race, I learned that, in order to attempt to understand the current picture of racial inequality in America, you can’t disconnect our country’s history with racism from the present, which means that the Confederate flag will always represent slavery. Phil also used to give speeches at packed Pantera shows about blacks hating whites, as if reverse racism is actually oppressive.

Despite their punk and anarchist roots, James and Lars of Metallica have become greedy Republican assholes, and they haven’t released a decent record since the early ’90s. While their first four albums are classics, Metallica is also largely responsible for what I like to call douche metal—bands like Godsmack, Creed, and countless others that regurgitate the generic rock that Metallica popularized with The Black Album.

Throughout the years, I’ve also thought a lot about Metallica’s lawsuit against Napster. While I totally agree with the idea that artists should be able to earn a living with their craft, I think Metallica’s lawsuit stemmed from their own shortsightedness about what the internet is and the changes it would bring. Also, the members of Metallica were millionaires when they sued Napster. Downloading and streaming makes it harder for musicians to earn a living, but the internet has also placed new levels of power in musicians’ hands in terms of distribution, as well as information about recording.

In examining my idol worship throughout my late teens and early twenties, I’ve realized that Slayer’s uncomplicated disavowal of religion has become a form of religion for a lot of fans. Also, the hatred in Slayer’s music often seems scary to me now. I’m still an angry guy that dislikes most forms of organized religion, but I try to be smarter about it now. The last time I saw Slayer, I remember feeling uneasy as I listened to people in the crowd rabidly chanting, ‘Slayer! Slayer! Slayer!’ Just a few years earlier, I would’ve been chanting right along with these fans. I also refuse to brush aside the fact that Kerry King, the guitarist of Slayer, is infamously homophobic.

But these thoughts have never been able to overshadow the fact that, when I listen to Sabbath, Pantera, Metallica, or Slayer, I still feel compelled to head bang. Although criticism creeps in, listening to metal is still an electric experience for me. Jamming to any of these bands at home or in my car, I can stop thinking for a few moments and just rock the fuck out. I still love the raw energy in metal, and heavy music is easily the most fun to play. I get to completely let loose, beating the shit out of my drums. I’ve played in several heavy bands throughout the years, and I’m currently jamming in a sci-fi sludge band.

My Pantera tattoo has been replaced by a fat, two-inch-long scar. Only a sliver of Tony Iommi’s guitar remains on my left wrist. A jagged white scar slices through the splotch of black ink that was once the guitar body. A massive shard of pearly scar tissue is consuming the skull on my right forearm. The bats that went through the skull jut from my scar.

With a queasy sense of regret, I often wonder who I’d be if I’d never begun this excision process. At the same time, I think it was inevitable that I’d become this neurotic, isolated, self-loathing, awkward and bespectacled man with short blond hair, a red beard, and scars.

Pick up a physical or digital copy here.