It had been months in the making, but there I was. Reading my Japanese Independent Music book and picking up whatever scraps I could online of the supposed ‘hot spots’ for Japanese noise music could not have prepared me for what I was about to see. I had reached noise mecca, and in the midst of it all lay a circuit-bent black dial phone operated by one of the most exciting noise acts I’ve ever seen.

Japanese noise music’s boom period in the late 80s and early 90s has left a lot of ghosts behind. On my search for it, everyone I asked in the most ‘alternative’ music shops I could find remembered the period like one might remember a wino on their street corner. They recalled the vaguest of details. Odd nights at venues were hazily talked about and great pauses were taken when trying to remember what stores sold the music. The information I got didn’t tell me much other than the fact noise was not as easy to find as I had thought it would be.

My mistake was a common one made by Westerners thinking about or looking for Japan’s noise scene. I assumed this music, with its genre roots firmly in Japan, would be ubiquitous. But as peculiar, beautiful, strange and fascinating a place Japan can be to the unfamiliar eye, it is not so strange that Hijokaidan take the place of Queens of the Stone Age in the charts. Like anywhere else, noise lives in Japan’s underworld, down narrow alleys and in basement venues, held in the shadows by masked gatekeepers like Blackphone 666.

I found noise mecca thanks to an invite from Hiroshi Hasegawa (founding member of C.C.C.C. and now Astro) – and thanks to Hiroshi, and his wife Hiroko, meeting me at the train station and showing me the way – down some stairs in a tiny café called Flying Teapot located in Nerima, Tokyo. It was not the kind of place you would expect to find some of the most pioneering, and loudest, noise artists around. In fact, it was more like a place you would expect to hear an acoustic guitar or some spoken word. But where unconventionality reigns, venues can be surprising. It was the perfect place.

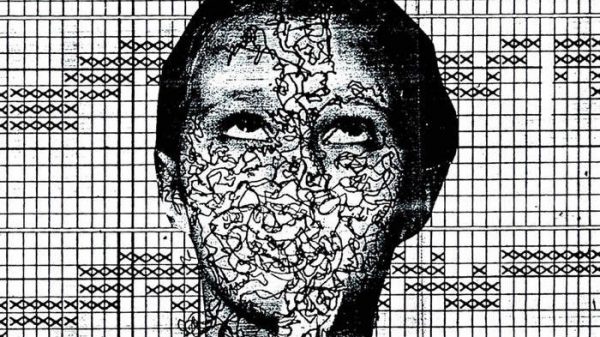

The gig which Hiroshi had casually invited me to was nothing less than the 2013 International Noise Conference, comprising of three American acts (one of which Miami’s own Laundry Room Squelchers) and six Japanese acts (including Hasegawa himself and the almost folkloric Toshiji Mikawa of Incapacitants and ex-Hijokaidan). At either side of the conference, like totemic pillars of Japanese noise, Hasegawa and Mikawa opened and closed the conference respectively. Genre-defining, exhilarating, virtuosic and ear-splitting, I was truly at noise’s centre.

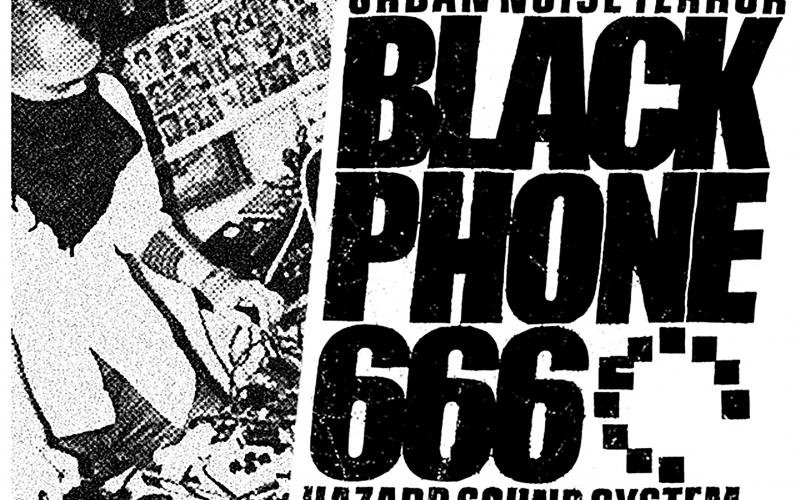

Performing in the middle of the conference, a young man from Japan sat at a table. In front of him a mixer with wires like octopus tentacles spilling out of it, and a black dial phone. Before his set, he tied a black scarf around his mouth. His set started slowly and quite boringly. The sounds dragged themselves along in a rather modest way. But then it quickly began to change. He started talking into the phone, which was mic’d. His voice emanated from it demonically as he slurred and growled deeply, adding texture and definition to it all. And then suddenly, unexpectedly, his sound exploded. Harsh feedback screeched from his mixer, echoing ghosts of our hosts’ band C.C.C.C.. He stood up and began screaming into the base of the dial phone which he had picked up from the table. The way he screamed reminded me of Prurient. This wasn’t beard-strokey noise, this was smash-into-whoever-is next-to-you, kick-and-punch-mid-air noise. This was the noise of Blackphone 666, a.k.a Kazuhiro Kajiwara.

It wasn’t long after my return home that I, surprisingly and eerily, got to see Blackphone 666 again at the Tusk Festival in Newcastle. On a festival that would see fellow Japanese noise crazies Endon close in spectacularly brutal fashion, Blackphone 666 pulled no punches in anticipation. His set was distinctly harsher than the one in Japan, without any of the meandering foreplay. He even flirted with some heavy industrial sounds and almost some dark dubstep bass textures. He left everyone speechless.

In an interview with Miami New Times, John Olson of American experimental outfit Wolf Eyes, said noise music is ‘completely, 100 percent’ over. Olson has a point. Out of the early-to-mid 2000 boom period of noise in the West, there was and still remains large pockets noise-makers obsessed with ‘transgressing the norms’ of musicality all the while failing to recognise that the transgression has since been normalised. But this is what is so exciting about Blackphone 666. Kajiwara is unashamedly a genre player. His noise reminds me of everything I love about noise music, echoing the likes of Prurient and C.C.C.C. while adding his own ingredients, and his black dial phone, to the mix. His noise reminds me that far from being dead, noise music is a genre to be cherished like any other genre, not only because there is still room for exciting things to happen, but for the reason that it has sounds, moves, gestures and ideas that some of us have grown to love, and the best artists are the ones who remind us just how much we love those things.