Besides writing on a couple of underground magazines, I am a high school teacher. More precisely, I teach Philosophy and History. And if making teenagers fall in love with the first is child’s play, the latter is always a really tough pill to sugar. Therefore, I borrowed from my middle school teacher one very effective strategy to catch my students’ attention when I see them heavy eyed: cheer up my audience with a filthy or truculent detail. Ok, that’s an old trick, but I swear it still works.

Of course, medical and military history are gold mines of repugnant anecdotes, and no wonder that sometimes these fields meet in striking, disturbing stories to put my students off their dinner. In this sense, one the most successful ones was the Waterloo teeth business. In case you never heard about it, it’s worth telling from the beginning, because Modern age dentistry is a quite interesting matter.

Ever wondered why George Washington never smiles in his portraits? The answer is simple: because his teeth weren’t definitely worth showing off, though he sported some very expensive prosthetics in his mouth. The same can be said of most of XVIII-XIX century people, especially of those who weren’t as wealthy as Mr. Washington and couldn’t afford proper remedies. Most of them shared nightmare smiles.

Sugar consumption was spreading amongst the population, at first between the wealthy classes of society and then, progressively, also in the lowest. Tobacco was already very common and appreciated (the great majority of Dutch adults used to smoke, sniff or chew tobacco already in XVII century). But we can’t say the same about dental hygiene, that moved its first steps to mass diffusion only in the second half of the XVIII century. By that time, people had at their disposal just toothpicks, cloths and their own fingers to clean their teeth and gums with.

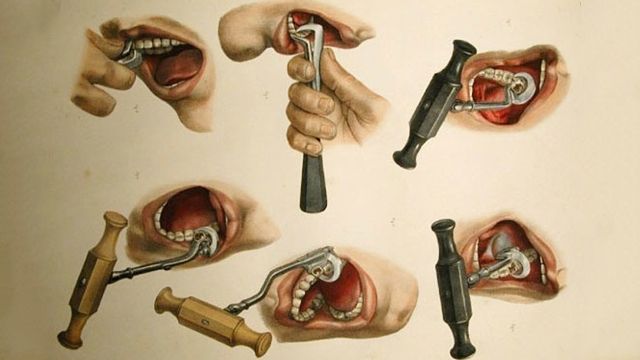

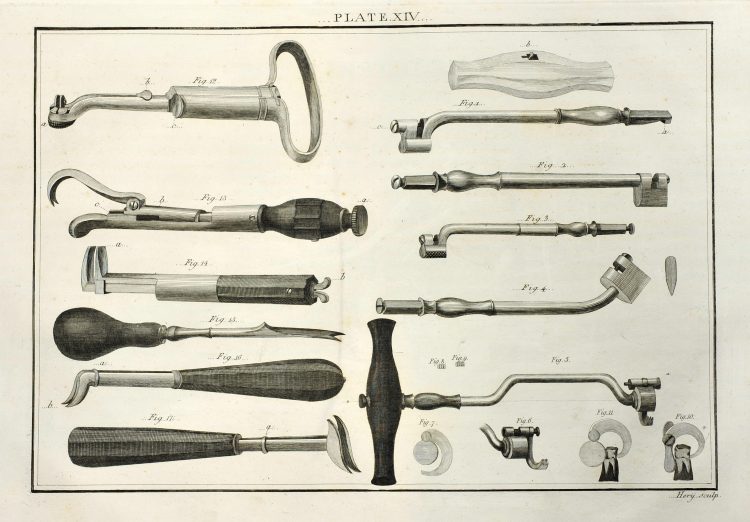

French surgeon Pierre Fauchard pioneered modern dental care in 1750’s- 60’s, inventing new tools for tooth pulling and, most important, indentifying sugar as the main responsible for tooth rot. Well, to tell it all Fauchard also recommended his patients to brush their teeth with urine. Which is even worse than the possible alternatives, such as crushed animal bones and gunpowder – also for the damages urine’s ammonia may cause to the mouth. Beyond these ingredients, other elements that could be found in toothpaste or toothpowder were dragon’s blood (which is actually a vegetal resin), chalk, soap, cinnamon and salt. And mouthwashes made with vinegar or animal blood didn’t seem to have a nicer taste.

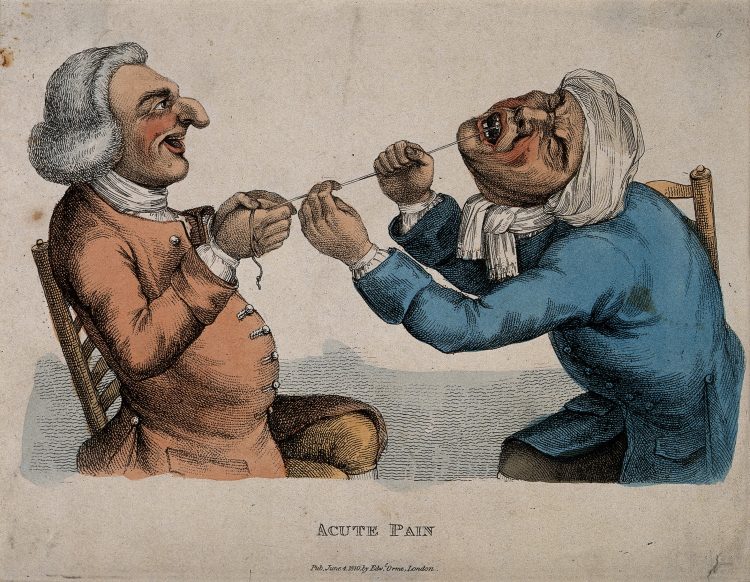

About twenty years after Fauchard’s studies, in 1780, William Addis made his fortune with the first mass-produced toothbrush, perfecting a tool he discovered…. while in jail. It makes no surprise that this little cattle bone brush filled with boar bristles was so successful: in an era when the only cure for toothache was having your hurting teeth pulled with no anesthetics by a barber, a blacksmith, a butcher or whoever (and paying a lot for it), spending few pence for an affordable prevention instrument should have been a quite good investment.

But what to do when you had no alternatives and your mouth already looked like a chessboard despite your young age? Well, dental beauty was as rudimentary as dental hygiene back then. Yet, dental implants were booming and false teeth were a great business.

Until the XVIII century, the methods of false teeth making were based on pre-Roman technologies: a gold bridge with a gold tooth at both extremities was filled with ivory or bone prosthetics, and then fixed in the patient’s mouth. However, while Etruscan artisans were very skilled and made great implants, the art of “making teeth” drastically regressed in the following centuries, and by the Modern age it reached a catastrophic level.

Dentures didn’t look real at all, were unsafe to eat with and – what’s worse – they literally rot in their owner’s mouth. In fact, the lack of enamel in bone or ivory caused a rapid decay of false teeth, and you can just imagine what it can taste and smell when you constantly have to chew some putrefying hippo bone.

Given these premises, it’s quite clear why the best false tooth was actually a real tooth. Human teeth looked better and lasted longer. Therefore, in XVIII and XIX century, the request for human teeth to use in dentistry was at its peak and it was a very, very profitable business. A row of real teeth could be sold for more than £30, which is unbelievable if we think that a servant may gain little more than £45 in one entire year of hard work.

The point now is: how to get human teeth? The answer involves body snatchers, extremely poor people and battlefields. That’s what we’ll be talking about in part II of this read.