During the 18th Century, medical schools were flourishing throughout Europe, and in many centres, there was a drive to standardize the curriculum to more consistently train doctors, which would,

During the 18th Century, medical schools were flourishing throughout Europe, and in many centres, there was a drive to standardize the curriculum to more consistently train doctors, which would,

amongst other things, slowly lift the status of the profession and better prepare provincial doctors to treat their patients according to new, scientific knowledge. The various schisms between different types of medical practices during this period – such as barber-surgeons, herbalists, and others – will not be explored here; however, medical science began drifting away from a system based on humourism to one seeking to understand the human body (and nature in general) based on direct observation “of the facts.”

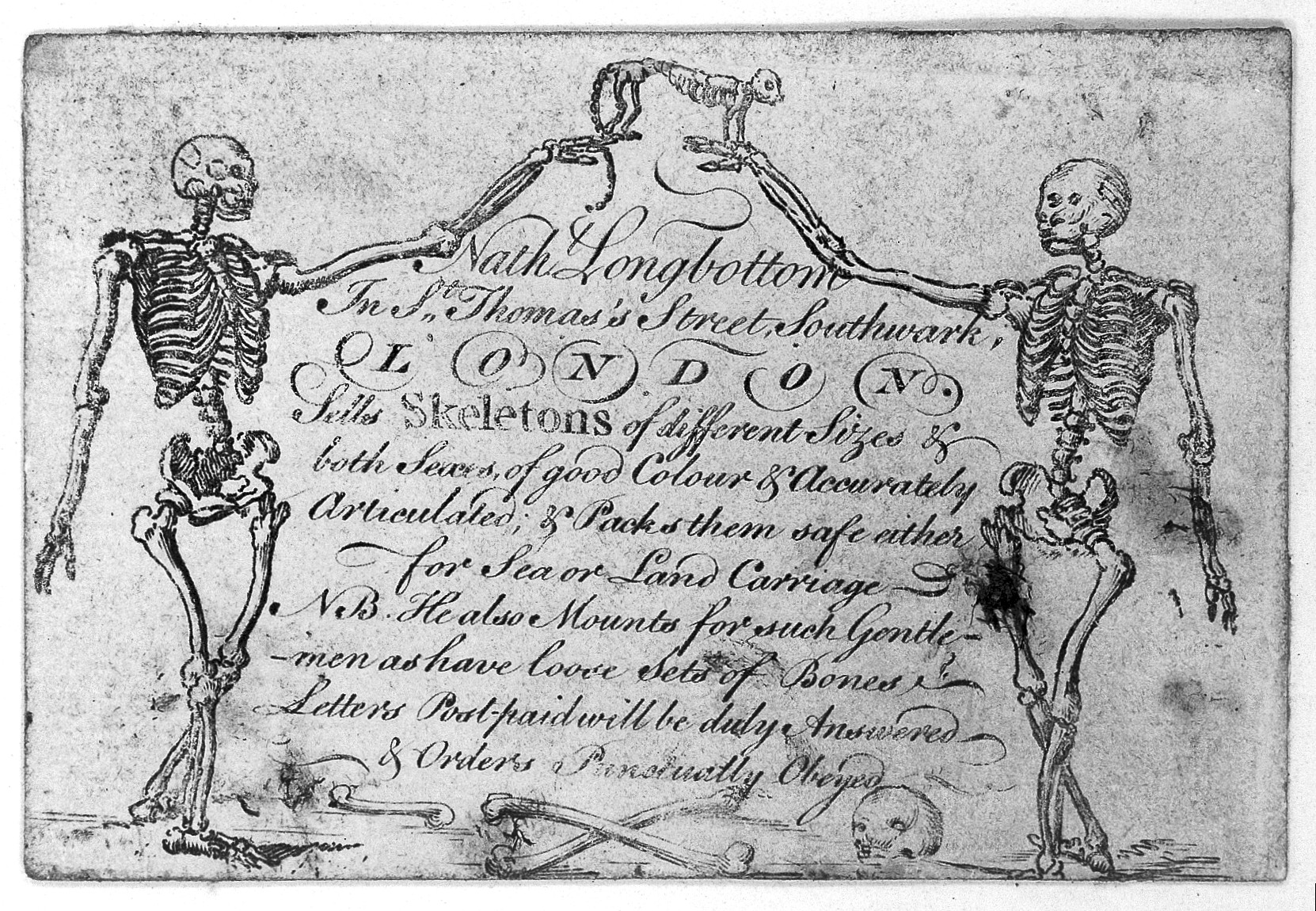

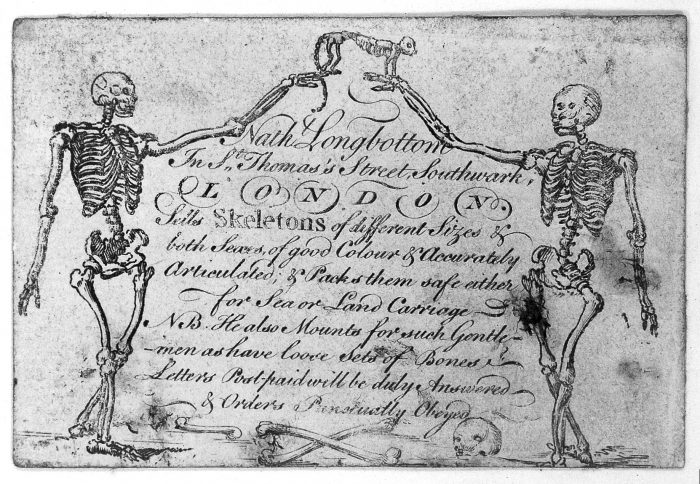

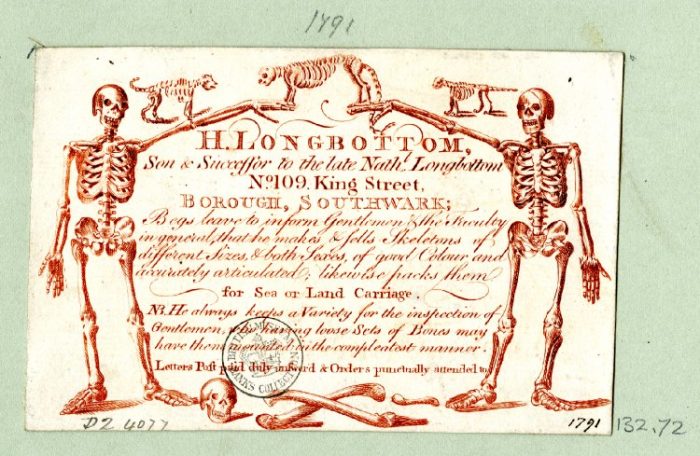

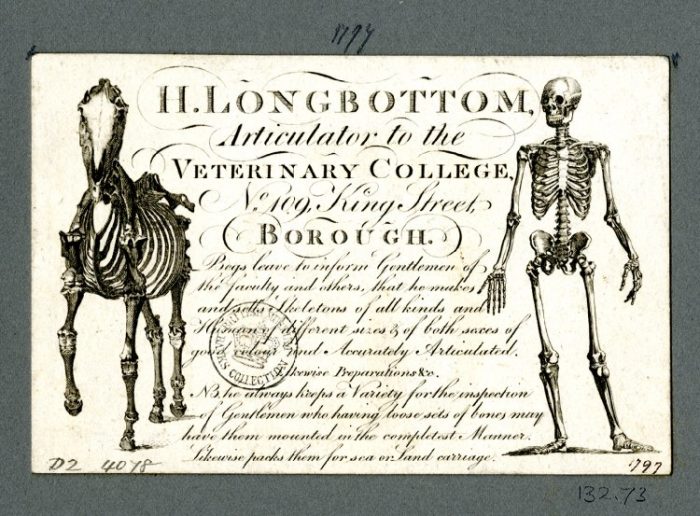

Naturally, this required more practical means to educate students, on a larger scale. Merely theoretical knowledge of the human body, for example, was inadequate, and greater demand was created not only for wet specimens and corpses for instructional purposes, but also skeletons. Merchants and other small-scale entrepreneurs saw increasing opportunity here, and began to trade in these specimens. One such example is the Longbottom family in London, whose trade cards are pictured below.

Though it isn’t clear where the Longbottoms received their wares, based on location, one could presume that St. Thomas’ or Guy’s Hospitals may have been some help. Additionally, articulation and mounting are offered as services on the trade cards, so the Longbottoms could have been some assistance to clients already in possession of human or animal remains, with the first and second cards also showcasing skeletons of a monkey and horse, respectively, in addition to their human counterparts.

Nathaniel Longbottom trade card courtesy of Wellcome Library, London

H. Longbottom trade card courtesy of the British Museum, London

H. Longbottom trade card courtesy of the British Museum, London