Torment & Glory We Left a Note with an Apology is out now on Sargent House

I’m really enjoying We Left a Note With an Apology. It sounds quite unlike anything else you’ve done, yet still sounds like you. It’s my understanding that its origin was a dusty, poorly cared-for copy of Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska at a friend’s house way back in the mid-2000s, and the record player’s needle wouldn’t stay in the groove, instead affording unexpected distortion with acoustic guitar or a voice intermittently making its way through the noise. Did that set the tone for the whole project then and there, or was it something that grew with you over time? While some song ideas initially intended for Torment & Glory have gone to other bands and with respect to the fact that the first impulse for this project presented itself roughly a decade and a half ago, at what point did you feel like you’d amassed enough material to make a record? Were there any particular moments of note where you felt like you’d reached a major milestone?

Glad you’re digging the record. I appreciate the kind words.

That night with Nebraska was an inspiring moment because I was hearing an accident, but there was something really beguiling about it. I was already a fan of the album and I’d heard it countless times, but this time it was buried beneath all of this murk and distortion. It was like hearing Merzbow’s Pulse Demon with these little song fragments occasionally rising out of the white noise.

I’ve written songs on guitar for as long as I’ve been playing music. In my twenties, a lot of that stuff wound up turning into material for an old indie band I played in called Roy. Sometimes stuff would work its way onto an album for one of the more abrasive bands I played with—something like “Afghamistam” by Botch or “Perpetual Bris” by These Arms Are Snakes.

In some sense, yes… I think hearing Nebraska that night set the tone for the project, even if the end result is much more concrete and song-based than I had intended. I think there was always a little bit of a struggle with figuring out how to balance the songs with the noise, and I knew I was eventually going to have to deconstruct and bury a lot of the refined aspects of the material to replicate that dust-coated stylus sound. So I think I sat on a lot of this material for so long because I didn’t know when the individual songs were finished, and all my attempts at burying them in white noise were unsatisfying. And then there were other records to make, tours to go on, all of that stuff. And then I lost my voice, so that was another setback.

Really, I only made this record when I did because it was winter in the Pacific Northwest and I knew I was going to deal with seasonal affective disorder if I didn’t find a positive creative outlet. I went through all my old demos and found an album’s worth of material that I felt good about and took a stab at recording them at home.

I think the real milestone was sending “Boylston and Pike” to my friend Ben Chisholm after he offered to help mix the material. He really transformed the song, and between his expertise and his enthusiasm, it made me inclined to take the whole project a little more seriously.

Some press materials state that losing your voice in 2019 was the impetus to flesh these songs out into an album, in terms of using your voice to reclaim your ability to sing. I can only imagine how frustrating that experience must have been as a musician. Is this possibly something you’re referencing by adopting the moniker Torment & Glory, or is its significance rooted somewhere else?

Losing my voice to vocal cord paralysis was a big motivator for seeing the project through. My voice isn’t 100% back, but it’s way better, and it improved considerably over the course of working on vocals for the album. But the project name isn’t related to that. Back when my friends in Minus the Bear were tracking their Planet of Ice album, I’d stopped by the studio and browsed through a Time-Life book on the Arctic that they kept around for inspiration. There was a chapter on glaciers called “Tormented Migrations to Doom” which just sounded like the most metal thing ever. I swapped Doom with Glory partially to avoid a doom metal association and partially to avoid naming the project after someone else’s idea. Funny enough, I only changed it to Torment & Glory after I started recording the album because I googled “Tormented Migrations to Doom” and it brought up a Bandcamp page for a synth project, and it happened to be my friends Chuck and Neil from Wovenhand and Planes Mistaken For Stars. They’d seen the same Time-Life book. Great minds think alike.

You’ve been active in music and touring more-or-less constantly across 3 decades. When lockdowns happened, that abruptly ceased. Is it fair to say that this is the longest amount of time you’ve had between tours? Furthermore, I can only imagine that the ramifications of social distancing/isolating are only enunciated when you are accustomed to constantly being on the move. Which aspects did you find the most challenging?

Additionally, I’ve certainly read interviews where you touch on the topic of dramatically shifting gears when you come home from a tour. To what extent would you say that this had an impact on finishing We Left a Note With an Apology?

Yup, this is by far my longest break from touring. I was really bummed we had to cancel the Russian Circles European tour with Torche because it was looking to be a really fun tour. We’d wanted to tour with Torche for years; the routing was amazing, and the ticket sales surpassed anything we’d experienced. So that was a real letdown. But honestly, I was happy to take time off. I had my vocal cord paralysis thing and some persistent gut trouble that I think was ultimately the result of all the traveling. Mike was dealing with a lot of repetitive stress injuries in his hands from playing guitar, so it was good for him to be able to find a good physical therapy regimen for those issues. And we’d toured so much on the last album.

It was good to have some time off, to be home, and get into a pattern of better habits. The big challenge was just remaining positive in the face of all the uncertainty. I was lucky to have a husband I could lean on financially, but I have bandmates and people in our crew who really depend on touring for their livelihood. And there’s the larger ecosystem of the club/nightlife world to worry about. I’m now at the age where a lot of my friends aren’t just employees in the entertainment and service industry, they’re business owners. So knowing that they were facing financial ruin for something completely outside of their control was really upsetting.

And yeah, usually when I get home from tour I have a lot of difficulties recalibrating my brain because I’m an inert person, and I feel like I should still be in motion and following a set schedule. To suddenly have nothing but free time and no obligations is nice for a day or two, but it’s difficult to switch into self-motivated productivity, especially since I’ve been in performance mode as opposed to creative mode. It can be tough to get in the creative mode because so much of your sense of self-worth as an artist is bound up in your ability to create, and you really have to remind yourself that those first few days of trying to write are always going to be frustrating, but you have to work past it. I think having months of downtime was crucial to Torment & Glory. I was able to put in a few hours of work on it every day for two months, and I rarely have that kind of free time at my disposal.

With shows starting to happen again, how are you feeling with regards to touring in the present climate?

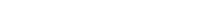

Well, These Arms Are Snakes are doing two reunion shows this weekend, so I guess that demonstrates that I’m willing to do it, but I’m nervous about it. We committed to the shows back before the delta variant had taken hold. You have to provide proof of vaccination and there is an indoor mask mandate, so that should help reduce the risk factor. Ultimately, infections are where they’re at because people refused the vaccine, so we’re being held hostage by a contingent of society that’s predominantly either selfish, uninformed, or taking a really asinine political position, and I can’t sit around and wait forever while I watch the music community suffer because people are worried that they’re gonna become magnetized or because they’re trying to own the libs. If you don’t wanna get vaccinated, that’s fine. But you don’t get to participate in communal events. That’s the deal.

I know there are people who are really adamant about the New Zealand model where we shut everything down until the virus is gone, but we’re such a huge country and such a major hub that I don’t see that happening. And I’ve noticed that the “shut everything down” proponents tend to be people who can work remotely, so it’s an easy position to take up when it doesn’t affect your livelihood. Meanwhile, all my friends who own bars and restaurants and coffee shops are bending over backward to comply with the laws and CDC guidelines, and they have no financial safety net if we go back into a shutdown. If there was some actual relief for self-employed people and small business owners, I would be more open to going back into the shelter-at-place model. But as it is now, it would financially ruin the majority of my friends and colleagues.

This record is 100% you, correct? While I’m sure there are pronounced differences between every band you’ve been in, what did you find most challenging about tackling this one completely on your own? I also found it interesting that despite it being a solo effort, you use the word “we” in the album’s title. Any particular significance to this that you’d like to touch on, or am I reading into it too much?

Yup, the record is all me. I told Ben that he could add auxiliary instrumentation if he had any ideas, but he was more adamant about keeping it a proper solo record than I was. When I first started tracking the songs in Logic, I was really looking at the process as a trial run. I was really worried about tracking the fingerpicking on the acoustic guitar, and I wasn’t sure how much work it would take to get through a song, because it’s rare that I make it through a song without a flubbed note or two (or twenty). This isn’t Tape Op so I don’t wanna get too deep into the technical aspects of how I recorded it, but I really just wanted to figure out a system so that I could go through the guitar parts section by section in a fluid way without having to do a bunch of punch-ins and edits. It wound up being pretty easy once I got a system in place. The vocals proved to be the bigger challenge… it would take a day or two of singing the songs before I could get a halfway decent take.

The “we” in the album title isn’t a reference to the project. One of the lyrical themes of the record involves reflecting on teenage rebellion and all the things my friends and I would do in the name of thrill-seeking. A lot of it was reckless. Some of it was destructive, even if it wasn’t necessarily meant to be malicious. So the title is a way of acknowledging that we were in the wrong, even if we weren’t trying to hurt anybody.

Additionally, what stood out to you the most about making a record by yourself as opposed to with bandmates? I ask this, being mindful of the fact that your bands haven’t really had the most traditional approach to writing songs, and I know that you feel strongly that music should be deserving of a long shelf-life.

Well, the ideas didn’t have the vetting process of going through multiple band members. So while there was this total creative freedom, there was also a lot of self-doubt. Every band dynamic is a little different, but I assume every band has to find a balance between letting every member have a say while also acknowledging that everyone has to put their ego on hold for the good of the material every now and then. I love the band arrangement because I love seeing how a song develops and goes in unexpected places when different people insert themselves into the process. But if you have a concrete vision on the front end, it can be really frustrating to see it get compromised.

Ultimately, Torment & Glory felt like an opportunity to be in full control, and that’s made working on the new Russian Circles album way more relaxed on my end because I don’t feel like my vision and voice as an artist is solely bound up in that material. That said, holy shit… I’m so pumped on the new Russian Circles record we’re recording in September. Maybe I need to always make a solo record right before it because it’s taken the ego out of the process and allowed me to have fun with the material instead of feeling like it has to be a definitive statement.

As I noted above, this sounds very different from any of your other output, yet it still sounds like you. The closest points of reference to me would be a handful of Roy songs, or even Botch’s Afghamistam. Was there ever a conscious effort to adjust or re-work parts of songs if you felt you were venturing too close to retreading territory you’ve covered in the past?

In hindsight, I could see there being some sonic parallels between the end of Russian Circles’ “Praise Be Man” and the end of “Mexican Hat, Utah,” but in the actual process of writing and recording, I didn’t really encounter that problem. Torment & Glory felt different enough from the things I’m generally known for that I didn’t worry about things feeling formulaic. And while I think there are vestiges of some later Roy songs in the Torment & Glory sound, I think I’ve developed as a musician to a substantial enough degree over the last fifteen years that I’m not in danger of repeating myself. I mean, there are barely any strummed chords on the whole album… everything is fingerpicked arpeggios or layered notes, so that alone is a big difference from the more youthful ham-fisted approach of the stuff I’d write for Roy.

Approximately 15 years is a long time for a record to come together. To what degree would you say the songs evolved over the course of that time? Did any in particular unexpectedly veer off in a completely different direction than you had first envisaged?

Well, as I mentioned earlier, I anticipated all these songs being buried in noise. And while that element is there, it’s way less prominent than I had initially intended. I’d say that “The Kick Drum” is way more layered than I had envisioned when I was fleshing out the primary acoustic guitar patterns, but I struggled to cut back on the auxiliary guitar and bass work once it was in the mix. The whole middle distorted section in “No Big Crime” was kind of a surprise too. I wanted to fill out the sonic space there, and I just kept hearing additional harmonies. That was another motivator when I first started recording the material… I’d done rudimentary demos on my Fostex four-track machine, but I figured I should map out any overdubs so that if I ever went into the studio to properly track these songs I wouldn’t be wasting the engineer’s time trying out ideas. If I’d gone into the recording process thinking these were going to be final versions of the songs, I might have been less adventurous, but because they were seen more as exercises and demos, I gave every idea a try.

Are there any particular influences that you unexpectedly found yourself indulging on this record that wouldn’t have had a place in any of your bands?

I mean, I think the whole folk / Americana / country angle is pretty much verboten in any of my other bands. Ha! Not that those guys have an aversion to that stuff, but it’s such a marked contrast to our normal sound that it wouldn’t really have a place in our catalog.

Unexpected influences… that’s a little harder to pinpoint. I was really inspired by records made by people that didn’t have a lot of expertise or money involved. I was really impressed by what my buddy Evan did on that last Jaye Jayle record. He basically recorded all the instrumentation on his phone while he was on tour. It was like a little travel log of a year in his life. And then he went back and overdubbed vocals and had Ben Chisholm work on the songs. Have I mentioned how much Ben rules? That’s the primary theme of this interview.

But yeah, the Jaye Jayle record, the ZOMES records, the home recordings of Jackson C. Frank. Hell, Darkthrone has been an enormous inspiration these last three or four years. It’s a huge reminder that you don’t need fancy gear or a great recording to make amazing records.

Other than that, SUMAC has been delving more and more into the improvised side of our sound, and that’s prompted me to dig deeper into a lot of artists that work in that realm. So it’s been exciting to listen to something as fearless as Peter Brötzmann or Keiji Haino or The Necks or Don Cherry or electric-era Miles Davis and try to apply that adventurous spirit to my work. I worked on a lot of the supplementary instrumentation on the record by setting up tracks dedicated to improvisation, and I’d just let the tape (or rather, the 1s and 0s) roll and free-write on top of it. A lot of that stuff turned into more fleshed-out parts, but some of it stayed as is.

As someone who arguably spends more time onstage than the majority of musicians, do you see yourself performing these songs live?

That wasn’t my intention, and I don’t really like the idea of trying to play these songs to an audience that doesn’t know the material. But if an opportunity arose to play a show that felt appropriate vibe-wise and I had time to recruit people to help fill out the songs… maybe?

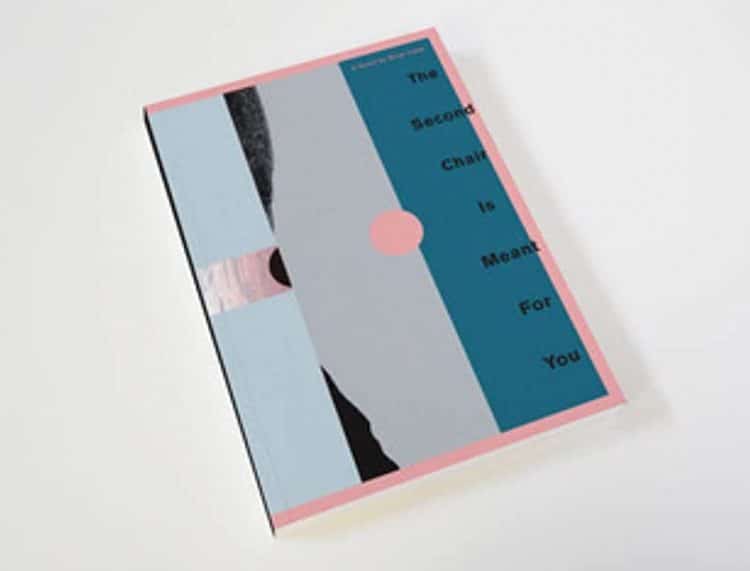

I’ve also always been a huge fan of your writing, which I believe I was first exposed to when I came across the These Arms Are Snakes tour journals you wrote. I have actually been hunting for a copy of The Second Chair is Meant for You to no avail for years now. Any plans to see a re-pressing?

I don’t think so. Or if I was to do another edition of it, I’d like to do some editing to it. There was a miscommunication between me and the designer, and it never went through a final round of proofreading, so there are a bunch of typos in it. The Second Chair was a lot like the Torment & Glory album… it was an experiment and a way of seeing what the process would look like. Then I got to the end and figured “well, I put all this time into… might as well print up a few hundred copies and see what people think.”

Are you working on anything in that realm presently?

Actually, yeah. I have another novel that’s on, like, a sixth draft. I’ve got a buddy helping me edit it and he’s really transformed the work in a positive way. But I got sidelined with the Torment & Glory record and now I’ve got this Russian Circles album to work on, so I don’t see myself getting another draft finished until later this year. And who knows how many other drafts are gonna happen before it’s “finished.” Hell, I finished the first draft over three years ago.

Speaking for myself, having heroes in music like yourself was instrumental in my rejection of the prejudiced, homophobic views that I had crammed down my throat as a kid, as well as something that made me keenly aware of the importance of being an ally.

As an openly gay man primarily active in musical circles that haven’t exactly been the most welcoming to anyone who isn’t straight, white, and male for close to 30 years, would you say that much progress has been made on that front? I know that touring with certain Christian bands was particularly heinous for you.

One of the tough aspects of coming to terms with being gay in my youth was that so many of the stereotypes I was presented with in the ‘90s portrayed us in a way that I had a difficult time identifying with. Like, I wasn’t even sure I was gay because I wasn’t attracted to Calvin Klein underwear models. I wasn’t into the musical divas. I didn’t care about Broadway musicals or clubbing. I was attracted to, like, the dad from Webster, and I liked punk and hardcore. So as a fourteen-year-old, I had The Meatmen and Angry Samoans and Bad Brains making me feel like a pariah, but then I’d look at the stereotypes of the gay community and think “well, I won’t fit in there either, unless I feign an interest in all this pop culture stuff that doesn’t speak to me.” Fortunately, I found the more progressive and political realms of hardcore where homophobia wasn’t tolerated.

Now there’s the inverse problem, where there’s all this toxic masculinity in the gay community and you have these “no femmes” attitudes and bro-gays who are obsessed with being “straight-acting.” Fuck that. Fly your freak flag. It’s amazing to see the advancements in the public’s perception and embracing of the LGBTQ+ community. But I also think we have a ways to go in getting over our gender hang-ups.

Overall, the underground music communities I’ve been involved with have always been more progressive than the general population, but no scene is a utopia. We can always work towards being more empathetic human beings.