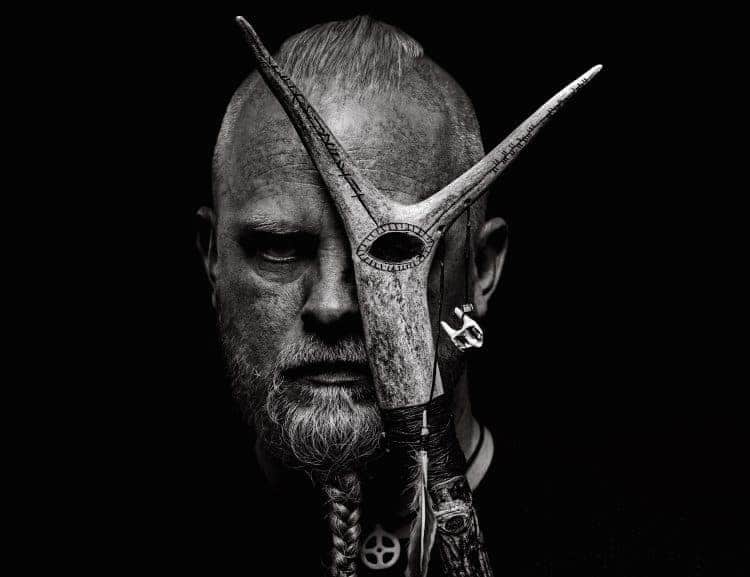

Almost twenty years ago Einar Selvik had the idea of bringing Nordic pagan wisdom into the modern era. His goal was not to recreate that time but to make it relevant for the present. He formed Wardruna, which would use Nordic traditional instruments such as frame drums, goat horns, and various stringed instruments, like kraviklyrs and jouhikkos, as a backdrop for his lyrics about the Runes, and the Norse Eddas. Over time, with a group of collaborators that include Lindy Fay Hella, and, at one time, the legendary Gaahl, Wardruna released the Runaljod trilogy. Each subsequent release found Einar and Wardruna moving beyond a cult following and toward greater mainstream success. By the time the group released the third in the series; “Ragnarok,” it debuted at Number One on Billboard’s World Album Charts. The band’s music has also been used in the popular “Vikings” tv series, and Einar is currently featured prominently in Ubisoft’s recent “Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla” video game.

Now, after a delay in release due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Wardruna’s newest work “Kvitravn,” is ready to ring in the new year with the band’s trademark ancient epic sound. The album was more than worth the wait, and is, in this writer’s opinion, the band’s most accomplished work to date.

The work is based around the concept of animism, or the belief that there is an animating spiritual force throughout nature. In a press release for “Kvitravn,” Einar discussed the meaning of the name, which translates to “white raven,” explaining “the raven is an animal I have a totemic relationship with, which is why I chose that for myself, but although this album is in a sense more personal and more down to earth than before, it is also quite obscure. I delve into the philosophical, the esoteric, the Nordic myths and how these old traditions define human nature and nature itself. So the white raven was not chosen as the title because of my name, but more due to the ideas which inspired me to take that name in the first place.”

This combination of the personal with the esoteric makes for the most immediate and assured sounding record in the Wardruna canon. One need only listen to opener “Andvevarljod” to gain a sense of the scope of this album, which is simultaneously grandiose and sharply focused, like a raven surveying the vast expanse while honing on prey. I was lucky enough to speak with Einar on the eve of the release of “Kvitravn” to discuss animism, the problems surrounding the word “Viking” and the importance of not climbing into a tree without roots.

You came out of the metal world to create this project that is wholly unique and has now influenced many other artists, I want to talk at first about the origins of Wardruna and the use of traditional instrumentation. What was your original intention with Wardruna, and how has that changed, if at all, over time?

ES: There are many layers to it, but I guess one of the main factors was that I really wanted to hear music that interpreted our old traditions and myths more on its own premises, rather than just borrowing bits and pieces here and there, so I envisioned this project using relevant instrumentation, sounds, language, record in relevant settings, etc. Go as far into it, or as deeply into it, and allowing it to find its own voice. That and I felt that there were so many things from the distant past that were just lying there in the corner gathering dust that I felt deserved being voiced. There are so many things that still carry relevance, and so giving voice to some of these things were the main driving factor.

How did you reconstruct that? It’s kind of impossible to reconstruct that past. I think anyone that is involved in Norse mythology, Norse paganism, or Norse scholarship has that hurdle. So, what were your parameters and touchstones to say this instrument belongs, this instrument does not? What informed the sorts of choices you made to craft your sound?

ES: Intuition is a big part of that factor, especially in terms of what fits where. For me, it’s never been about trying to recreate music from any specific time period. The instrumentation ranges from Stone Age to Bronze Age through the Migration Period, Viking Age, Medieval times, and even modern input. Of course, when I started to fully dig into the Nordic musical history like twenty years ago, or so, that’s when I started to actually go into it and along the way, some of the instruments stuck out and I just knew right away I had to have them be a part of this. As far as deciphering or knowing how one used these instruments that’s of course a whole other discussion and a giant jigsaw.

You need to have a broad overview of the sources. Even though we can’t say for sure exactly what music sounded like in the Bronze Age or the Viking Age there is a lot of evidence pointing us in a direction, both found in the limitations of the instruments and that for some instruments we actually have a living tradition. There are archeological findings sort of confirming the tonality didn’t really change that much in the last 1500 to 2000 years. Then you have, of course, the poetic tradition that gives us lots of clues and written sources, etc. So, it’s a jigsaw.

One thing that has always impressed me so much about your work is your dedication to scholarship. I know you have worked with professors here in the states [Mathias Nordvig], and other experts in Old Norse language and things of that nature. Tell me about the importance of scholarship in your work.

ES: Yeah, one of my mantras is that you shouldn’t climb into a tree that doesn’t have roots. So, having a solid ground before you venture into the more creative processes, or the intuitive processes, whether or not it’s the musicology or the themes I’m working with, I find that very important. At the base of it all is always some form of academic approach. I see it as a great advantage that I sort of have both camps represented and I guess that’s partly what academia is acknowledging me for as well, they see the value in doing both. They see that doing a thorough job in terms of the primary sources and then applying a practical set of logic and methodology has a value to it, and can bring us one step closer to actually illuminating some of these things.

Let’s talk about the theme of the new album “Kvitravn.” Previously you have explored the Runes and the Skaldic tradition and now, with this, you are focusing on animism. I’m excited that you are approaching that subject, it’s incredibly fascinating to me. A lot of people, when they think of Norse paganism or paganism in general, they think of gods; Odin, Thor, Freyr, but animism is a huge part of that pagan tradition around the world, including Norse and Germanic. Can you talk about what animism is, because I don’t know that a lot of people know what it is outside of pagan and religious studies circles, and can you discuss how you approached it and applied it in the new work?

ES: Animism, just so that is clear, has been very central from the get-go in this project because it is so present in the Norse culture overall. Now I know some people, even scholars, which in my opinion some of these theories are quite outdated, they like to separate paganism or the old Heathenry from animism and call them two separate things. I would say that’s quite an outdated way of viewing it. It’s so present in the daily life of the old way of viewing the world and relating to nature, etc. They are very much connected. I guess the old-school definition of animism is the idea that everything has a spirit or a life form or a frequency or an energy, and yeah that’s part of it, but it’s so much more. This idea of empowering things and communicating with nature in a way, it’s kind of at the core of it.

If my music has a message, I would say it is very much promoting the idea that it would benefit us all if we had a more animistic worldview. By that I mean it doesn’t have to be a spiritual thing, it can be an attitude basically, the idea that nature is something sacred, and it’s a ring that you are a part of, not a ruler of. Of course, that element got changed and got lessened, even a long long time ago. Even back in Norse times, you see a change with what gods and goddesses become more and more important and what became less popular. Times change, so the ones connected to the Earth and land became less important, and the ones who you could take on your ship or abroad became more important and present.

In terms of the new album, I would say it walks and wanders in the same realm as the previous albums, but in a way, I zoom more in, to go more into detail and dive more into the human sphere and go more into our relationship to nature, both with animals and nature itself, but also in how we define ourselves as humans in this kind of worldview. We tend to separate, our modern way of defining a human is to say that we have a consciousness and then you have a body and if you a religious person, then you also have a soul. The old way of viewing it is much more complicated and much more detailed and layered. So, going into some of these concepts is what this album is doing.

You started the project in 2002, is that correct?

ES: I started the first recordings in 2002, I started thinking about it like 2000, 2001. That’s when the idea started to form more and more, but the actual first recordings were 2002, 2003.

Since then, we have seen a pretty big rise of acts that are at least following in your wake, if not directly influenced by you. Of course, the most successful being Heilung from Denmark, and I think they do a good job of sticking to the same ideas that you do, I don’t feel like there is any dilution with them, but I do wonder as you see more and more bands try to get that sound, do you worry about it being diluted? Do you worry about it losing its original intention, of being Earth-based, of keeping traditions?

ES: That’s kind of totally out of my hands. It’s the same thing when you put music out into the world, it takes on a life of its own, and creating this kind of a genre or a movement or whatever we should call it, I guess it’s the same there.

Of course, I see a difference within that scene also in terms – and I’m not going to deem the quality directly – but you see that there is a difference in how seriously one approaches these things in terms of actually using these instruments or, well, it becomes apparent that some of these projects to my ears, I can easily tell they haven’t really done their homework in terms of deciphering what is actually the most common traits for Nordic music, in terms of tonality or specific rhythms, etc. But, all in all, I’d say it’s great that people get inspired from all over the world to do these things and connect to it in their way. I totally respect that.

In terms of being worried, I’m not. I focus on the things that I can control and my own music. I also trust that many listeners will know the difference.

This last week in the States we had horrible things happen [the attempted coup at the Capital building]. One of the things that came out of it was this guy was wearing Norse tattoos and that created a whole controversy

ES: Yeah, I saw that.

I don’t even think he was pagan, apparently, he’s a Christian, but whatever, because it’s put people who are Asatru and people who are practitioners of Norse paganism here kind of on our heels having to defend ourselves, once again, against charges of racism, and certainly racists have co-opted these images and symbols throughout time. What advice would you give to people who are not racists and are sincere in their faith and practice having to endure these charges of racism when most people in Heathenry are not?

ES: It’s actually a difficult question, and it is, as you say, it’s really complicated. The fact is within modern-day Heathenry there is a lot of political movement within it, which in my opinion is not healthy nor relevant to Heathenry. I do my best to separate the two, but it is a fight.

The best medicine for ignorance is knowledge, of course, and I believe in that more than standing on the barricades and shouting at each other. I don’t think much constructive is coming out of that. So in terms of what advice to give, I’m actually not sure, because I know how complicated it is. Staying true to what you believe in, and voicing the fact that there are so many within this movement who actively oppose the use of politics within this scene, and that is actually the majority of this movement as well. The only thing we can do is just to continue to focus on what you are for and not everything you are against. That’s at least my focus; water the trees that you want to grow.

I don’t mean to ignore or be silent, and of course one should speak up, but pick your battles. I don’t see the point in discussing it on Facebook. You are never going to get anywhere by shouting on those kinds of barricades. So choose your battles, choose where you want to focus your energy, and focus always most on the things you are pro, rather than the things you are against because then you just feed the trolls.

You had to cancel your first North American tour because of the Covid-19 pandemic, are you going to reschedule that? I’ve got second-row tickets to Chicago, so I’m vested in this answer.

ES: That is also a difficult question. We are a bit unsure what is happening right now. We have a plan A, we have a plan B and we have a Plan C, basically, so which one it will turn out to be nobody knows at this point. Of course, it’s really unfortunate that we have to cancel or create a new tour, but we are coming back as soon as we can. That’ the only thing I can say for sure.

You made a series of mini-documentaries leading up to the release of Kvitravn. In one, you discuss the importance of songs, and how everything has a song. That reminded me a lot of the Aboriginal tradition in Australia and the singing of a song to go from place to place and if you know the song of a place and the things within it then you know how a thing works and you have power concerning it. I did not realize that practice was more widespread as it apparently is in Nordic tradition. Can you talk about that a bit?

ES: Yeah, it’s almost a common animist or nature-based religious phenomenon that I guess the Natives in America have it as well. Of course, from a Norse perspective, the sources don’t really give us much. There are some hints here and there and also in some later folklore, there are some hints about this. In the Finnish tradition – and they kept their song traditions for a much longer time than the rest of Scandinavia did, and also you see this very much present in our own natives in Norway, or indigenous in Norway, the Sámi people – this is very much present with them. Also, it comes down to language, if you know the word for a thing, for instance, if you know the oldest word for iron, you know how to make iron. Which is an interesting thing, because when you see the transition between Norse language and Proto-Norse, the language before Old Norse, you see that the same words had many more syllables in many cases. So imagine going further back in time, the words might have been much longer, and much more descriptive of each of these things. It is a fascinating tradition, one that I find great inspiration in, and one that I have applied to my own music since the beginning. This idea of seeking songs and asking for them, opening up and tuning into the things that are around us that we don’t necessarily see or hear consciously.

It really struck me to hear you talk about it, and it was something I really hadn’t considered before. We’ve lost so much of that tradition in the West.

ES: Yeah, and this is something you see within the folk medicine and healing traditions as well. If you know the song to cure a snake bite you need to know the song for the snake, etc.

That’s true, that’s a good point. I had not made that connection before.

I want to change the subject for just a minute. I got to interview Ivar Bjørnson a couple of years back when Enslaved were in the States and we talked a bit about him working with you, so I want to reverse that and ask you about working with him and how that came about and if you guys have plans in the future of working together again.

ES: Yeah, of course. We started out for the “Skuggsjá” project when we were asked to do a commission piece for the 200-year celebration of the Norwegian constitution. I’ve very thankful for that because it gave us an opportunity to work together. Now that was very much defined as being the combination of Wardruna and Enslaved, so that sort of had a set shape, to begin with. Then a few years after we were asked by the Bergen International Festival to write a commissioned piece, where we were basically more free to just dive into what we felt worked or didn’t work and decide what direction to take, and we decided to go into a more acoustic landscape with the “Hugsjá” record. It’s been a really great project to work with. I really enjoy working with Ivar. On a personal level, as a human being, he’s a really really great person, and as a musician, he’s such a creative force and extremely professional. Yeah, it’s been a pleasure to work with him and yeah, I definitely see somewhere down the line when our busy calendars sort of align in the right place that we will do something in the future as well. We both enjoy working together so I definitely see that happening at some point.

I need to ask you about the video game. You got involved in the “Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla” game, making music for it. I’m currently playing it and have the line “for those who fight, for those who fall” stuck in my head after hearing it so much on my longship. How did that come about?

ES: Ubisoft approached me a few years ago and wanted to know if I’d be interested in working together with them for the music. They were familiar with my work and were already using it as temporary music for parts of it. I liked the project. I liked the seriousness and the ambitiousness of it and also the vision for the musical side. We had a lot of the same visions for it. Something I felt lacking in modern productions, whether it’s “Vikings” or “The Last Kingdom” or whatever is that there are no skalds, no poetry, which was so central in this oral tradition and culture. So being able to give voice to that tradition was something I was very interested in and the fact that they were interested in doing that was a very good hook for me. So, getting to do that and also work on the more produced music for special missions and stuff like that was great. All and all it’s been a fantastic project to be part of. The people at Ubisoft have been great to work with, I have to say.

One last question, you mention there being no skalds in contemporary portrayals of Viking culture, part of it, and this kind of goes back to the racism thing, I think there is a one-sided view of…

ES: Yes, I know where you are going.

Yeah, go ahead and speak to that.

ES: There’s a reason why I never use the word “Viking,” and that’s because of that. It’s so loaded with this wrong stereotypical vision of what that time was. Of course, that is what is highlighted in most modern productions of that period as well. If you were to make a truly authentic time period drama from the Viking Age it would be a lot of farming, spinning wool and cooking, and (laughing) not as many epic battles, but that is the fact. For me, using that word becomes wrong because defining a whole culture by what a small number of people did for a short amount of time, it’s totally wrong. I try to remedy that whenever and wherever I can; that this does not represent the Norse culture. That whole macho battle, axes, and swords – that’s just a small thing, that’s just a small part of it. Of course, it was highlighted in the Sagas written for these kings and conquerors, but looking further we know that is just a small part of it.

I do see that as an important part of my work as well, nuancing these things and helping contribute and speak up about these things. That’s important.