In the 19th century, death was a big event. From post-mortem photography to memento mori jewelry to the year spent mourning the dead, they took that shit seriously. Coffins were a big deal too, so many companies sprung up to cater to the corpses in all manner of fancy ways. One popular trend was metal caskets, patented by inventors like Almond Fisk, Martin Crane, and James Renshaw to not only “prevent putrefaction” of the corpse, but in some cases, as with the Philip Clover “Coffin Torpedo,” the caskets were loaded with explosives that would go off if any grave robbers decided to resurrect the body. The Fisk model included an oval-shaped window at the top of the coffin so as to display the face of the deceased, and his models were decorative in an appropriately Victorian way. Check out an article about American 19th-century metal coffins and some awesome photos!

In 1931, the Fuller Company, charged with site clearance for the new Louisiana State Capitol building in Baton Rouge, began to uncover human remains. When construction operations were initiated, the project architects Weiss, Dreyfous & Seiferth had been informed that there was a possibility this would happen, as certain portions of the site had once been used as a cemetery. They had the site surveyed and any bodies that were easily located were disinterred and reburied. When one of the Fuller Company steam shovel operators struck a metal casket, construction was immediately halted, and a Baton Rouge treasure hunter named George Maher, Sr. was hired to locate any other such cases using a radio device.1

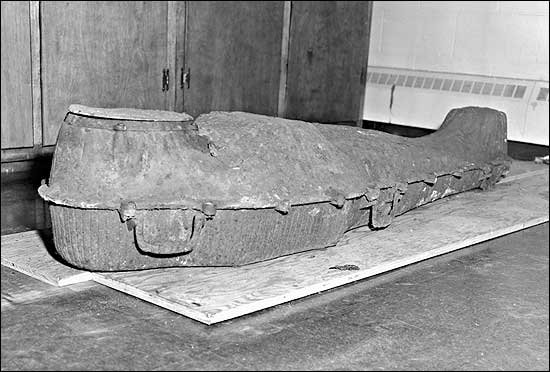

Maher ultimately uncovered some twenty-three metallic coffins.2 On 11 April 1931, some of the caskets — now removed to a collective burial site — were photographed as part of the construction documentation.

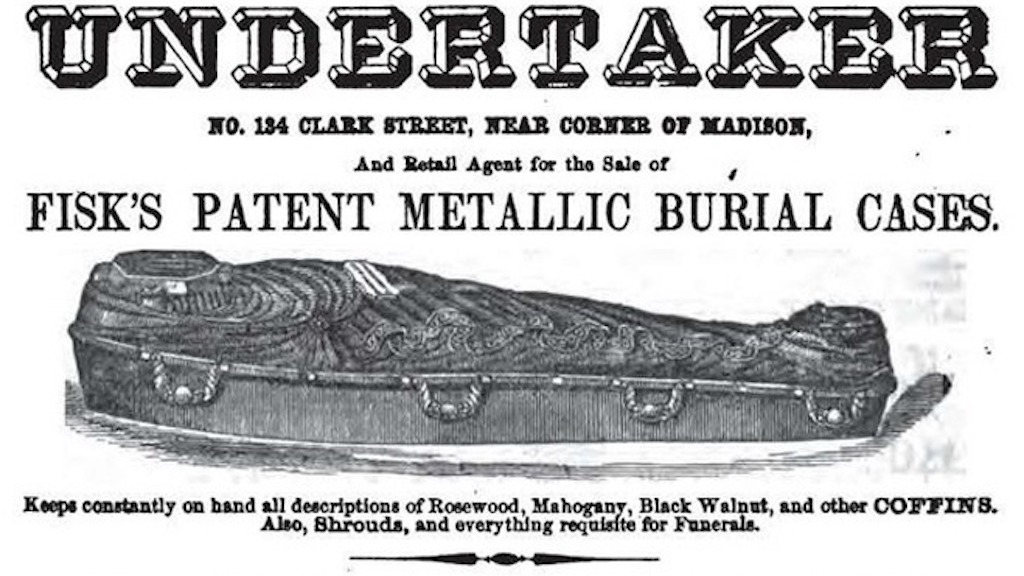

Such metal caskets were popular during the second half of the nineteenth century, and a host of entrepreneurs patented their own versions. Almond D. Fisk of New York famously patented the model above in November 1848. It featured a round glass window for the face that was securely mounted to the casket. Fisk suggested removing all air from the coffin in order to prevent putrefaction.

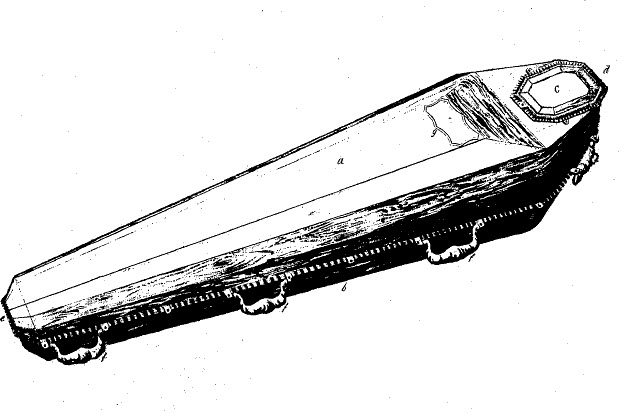

Martin Crane — representing Crane, Breed & Company of Cincinnati — patented this “Metallic Coffin” in March 1855. His model featured an octagonal-shaped glass window for the face, and a name plate, both with ornamental molded surrounds.

In 1861, Knoxville inventor James H. Renshaw patented this “Metallic Coffin,” asserting his improvements over earlier types. He employed unique bevels along the upper edges of his caskets.

Among the patent developers, one of the most unusual descriptions accompanied Philip K. Clover’s “Coffin-Torpedoes,” in which he claimed his invention would prohibit the “unauthorized resurrection of dead bodies” because any attempt to remove the body after burial would cause the death of the grave robber. His patent involved the use of spring-loaded explosives.

After the Civil War, Crane, Breed & Company established a New Orleans office on Magazine Street. They advertised their services in Gardner’s New Orleans Directory for 1867.

One of Crane’s competitors was T.W. Bothick, who sold “metalic burial cases” of the type patented by Lucian Fay in 1864. These were a much simpler form, with Fay recommending the use of sheet rather than cast metal.

It’s a good thing the 1931 State Capitol crew didn’t encounter any of the booby-trapped torpedoes!

1 Weiss, Dreyfous & Seiferth, Inc. Letter to Mr. Harris N. English dated 19 December 1931. Weiss, Dreyfous and Seiferth Office Records, Southeastern Architectural Archive.

2 Gene Bylinsky. “Search for the Pot of Gold.” The Times-Picayune (30 September 1956): pp. 134-135.