In the early morning hours of March 11, 1989, college students Mark Kilroy, Bill Huddleston, Bradley Moore, and Brent Martin decided their night of partying was at an end. Like tens of thousands of other high school and college kids, they had walked across the international bridge from Brownsville, Texas, to spend part of their spring break in the raunchy border town of Matamoros, Mexico, where the legal drinking age was only 18.

The four longtime friends left the bar and started walking toward the border, where they had parked their car. Along the way, Kilroy said he had to use the bathroom. He ducked into a darkened, overgrown park, only 200 feet from the border. The other three continued, confident that Kilroy would catch up when he’d finished.

They crossed the border and arrived at their car with Kilroy still out of sight. So they waited. After about two hours, they began getting worried. So they went back into Matamoros to look for their friend, to no avail.

The next day, when they still hadn’t heard from Kilroy, they went to the U.S. Consul in Matamoros. The consul assured the boys that Kilroy had probably wandered off and passed out and that he was sure to turn up soon.

But he didn’t turn up. So the boys, along with Kilroy’s parents, went to the Cameron County Sheriff’s Department in Brownsville. There, Lt. George Gravito took their statements.

It sounded like Kilroy had gone missing in Mexico, which was outside his jurisdiction, so he went to the Matamoros police. Gravito’s department had a long history of working with the Matamoros police, so Gravitos was surprised when they claimed that Kilroy had gone missing in the US; therefore, it wasn’t their problem.

There was, however, one agency that was willing to work with Gravito: the Mexican federal police — specifically, their drug enforcement arm under Commandant Juan Benítez Ayala.

The Kilroys, their friends, and both police forces searched for the young pre-med student, pasting up 200,000 flyers — in both Spanish and English — all along the Rio Grande valley. They offered a $15,000 reward. Kilroy’s parents met with officials all along the border, and his case was featured on America’s Most Wanted.

But despite numerous calls and tips, nothing panned out. Kilroy was nowhere to be found, and his case began to go cold.

Three weeks after Kilroy had seemingly vanished into thin air, a strange turn of events would not only uncover what happened to him, but reveal something far more evil and gruesome.

Ayala and his officers were working with American drug enforcement on one of the largest drug interdiction efforts the two agencies had ever executed. As part of that effort, Ayala and some of his officers had set up a roadblock near Matamoros.

All seemed to be normal until one car refused to stop. It drove right through the roadblock, leading to a high-speed chase. The car, with Ayala and his officers behind it, drove to a ranch in Santa Elena, just south of Matamoros. When the driver got out of the car, he seemed surprised that the officers were arresting him.

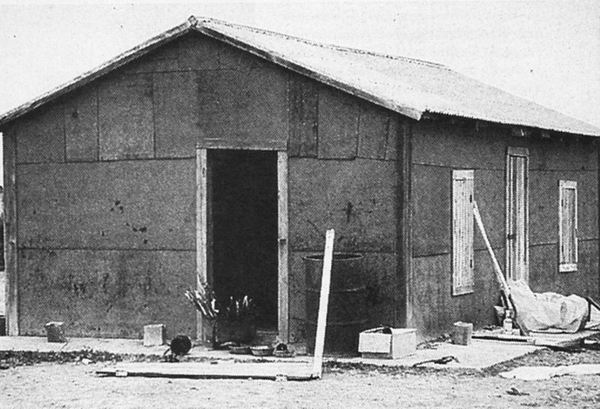

The officers conducted a search of the property and found hundreds of pounds of marijuana. They also noticed a small shed on the property. A foul, rotten stench emanated from the small structure. Looking inside, they spotted candles, an altar, a large cauldron, and other items they associated with brujería. None of the officers dared to search the shed any further.

But the marijuana was a major offense. In addition to the driver, Elio Henandez Rivera, several other men at the ranch were arrested, including Serafín Hernandez and an elderly caretaker.

At the station, the caretaker spotted Kilroy’s missing-person flyer on Ayala’s desk. “I know that man,” he said.

Ayala was listening. The old man told Ayala that he had fed the young man, who he had been bound and held in the back of a Suburban at the ranch three weeks earlier. As for what happened to Kilroy after that, the old man didn’t know.

So Ayala began questioning the Hernandez brothers about Kilroy. None of them would admit knowing anything — except Serafín. He readily admitted that he and his brothers had kidnapped him and taken him to the ranch at the behest of “El Padrino” (the godfather). He said that El Padrino had wanted them to bring him a smart, handsome American, one who was studying to be a doctor.

Why did El Padrino want them to kidnap Kilroy? There had never been any attempt to contact his friends or parents to demand a ransom.

Serafín answered very calmly: El Padrino wanted a human sacrifice.

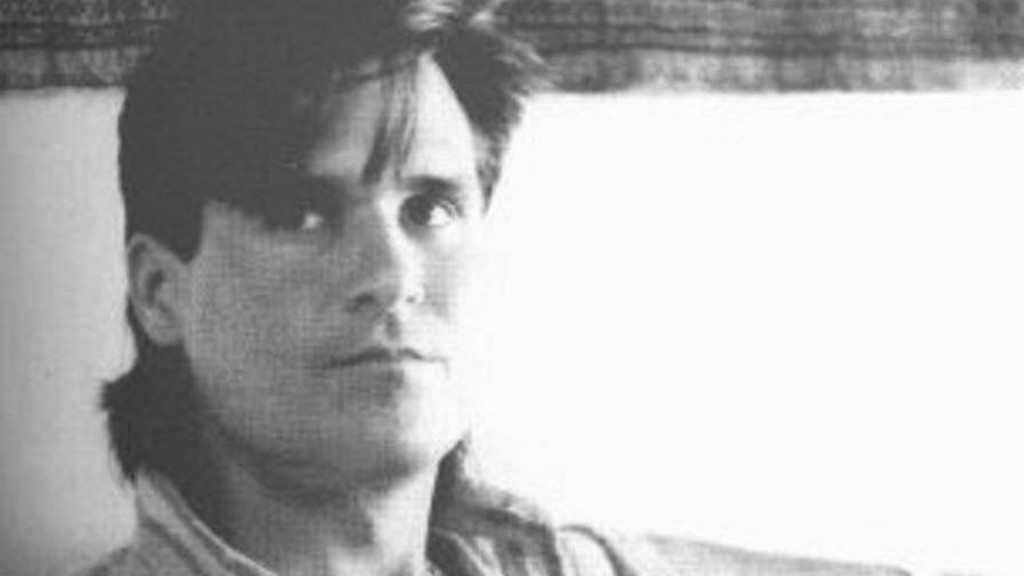

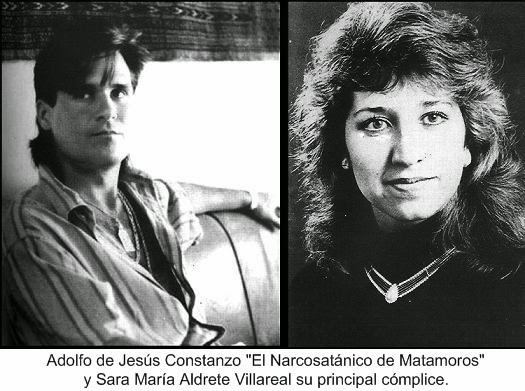

El Padrino, the officers would soon learn, was Adolfo de Jesús Constanzo. Born in Miami to a Cuban immigrant mother, Constanzo had been raised in the Palo Mayombe tradition, an Afro-Caribbean religion related to Santería, but considered to be much darker. Rituals often include animal sacrifice and the use of human bones — however, human sacrifice is strictly forbidden.

Constanzo’s mother believed her son to be a chosen one and performed rituals dedicating him to various gods or spirits and invoking their protection. She believed that he had strong clairvoyant abilities and that he could speak to the dead; they both claimed he had accurately predicted the assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan in 1981.

But she was grooming him for something much darker than telling fortunes. She would make him toture and kill animals, praising him for his cruelty when he did so.

At one point, his mother was arrested for keeping 27 animals in her tiny apartment; the floors were covered in feces and blood.

When he was 21 years old, his mother performed the final initiation on him, presenting him with a nganga, an iron cauldron central to Palo Mayombe rituals. The nganga is believed to hold the essence of the spirits, and the priest must sacrifice the appropriate items to the nganga to receive various blessings.

Now a full-fledged priest, the good-looking Constanzo was offered a modeling opportunity in Mexico City. He relocated there and worked occasionally as a model. But his primary income came from being a Palero, or Palo Mayombe priest. He opened shop in Mexico City’s Zona Rosa, or pink district, known for being welcoming to gays like Constanzo.

There, he performed various rituals — cleanses, fortune telling, healings, and others — for pay. Some of his clients were extremely wealthy and powerful, including law enforcement officials and drug dealers. The drug dealers, in particular, interested Constanzo, as this was where the real money was. He convinced several high-level drug kingpins that he could cast spells to make them invisible to law enforcement and that his clairvoyance could tell them which days to move their product safely. In return, the drug dealers paid Constanzo handsomely.

What they didn’t know was that Constanzo was bribing law enforcement officials so he could protect his clients.

It was through his drug connections that Constanzo ended up at the ranch in Santa Elena. It had long been a stopping point on the illegal drug “highway,” but with the death of the owner, the operation was in chaos. Constanzo stepped in, and using his charismatic powers, got the Hernandez brothers to believe in his twisted version of Palo Mayombe, convincing them that he could make them invisible to law enforcement and even bulletproof. Soon he took over the ranch and its operations.

The brothers (along with a few other followers) so believed in El Padrino’s powers that they participated in his rituals — including rituals of human sacrifice.

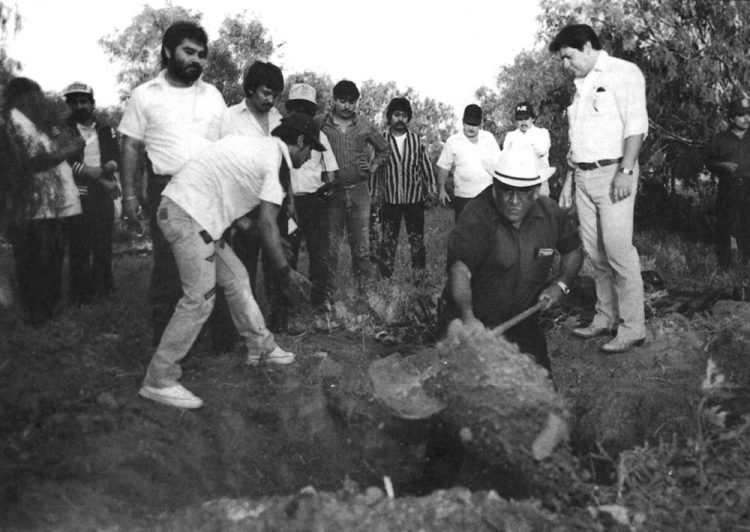

Ayala took the Hernandez brothers, in handcuffs, back to the ranch. “Show me where the body is,” Ayala commanded.

“Which body?” Serafín asked.

Ayala wasn’t in the mood to play games. But Serafín pointed out that there were several bodies buried on the ranch.

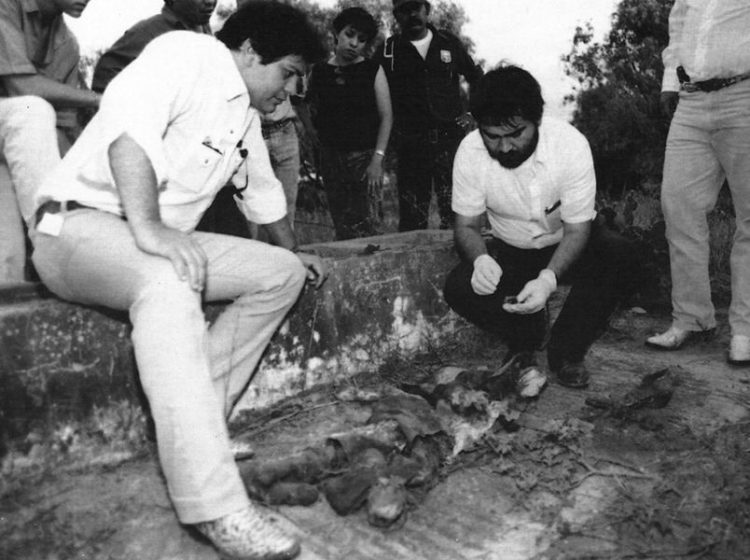

First, however, he was instructed to take them to Kilroy’s remains. He went right to the burial spot, noting Kiroy would be buried where there was a wire sticking out of the ground. Ayala asked why there was a wire there, and Serafín explained that El Padrino had wanted to make a necklace out of Kilroy’s vertebrae, so they had threaded a wire through his spine. That way, once he’d decomposed, El Padrino would only have to pull the wire out.

When Kilroy’s remains were uncovered, they spoke of a shocking death. His skull had been cut open and his brain removed. His legs had been chopped off below the knees. And his spine had been cut open and threaded with wire, just as Serafín had said.

Speaking casually, with no hint of remorse, Serafín detailed the last hours of Kilroy’s life.

He and his brothers had gone out to the bars, wading through the thousands of American tourists, looking for a victim that fit El Padrino’s criteria. That’s when they found Kilroy. They followed him to the park where he’d stopped to go to the bathroom. There, they flashed fake badges and told him he was under arrest for public drunkeness. They threw him in the back of their van and drove a few blocks away to wait for the other car driven by their brothers.

When they parked, Kilroy actually escaped. He ran, and nearly got away, when one of them shouted in English, “Freeze!” Out of instinct, Kilroy stopped, and the Hernandez brothers caught him and tied him up, placing duct tape over his eyes and mouth.

Just as the caretaker said, Kilroy had been left in the back of the Suburban at the ranch for several hours, until later that afternoon. That’s when Constanzo arrived and began the ritual.

Kilroy was dragged into the shed and forced onto his stomach on the filthy ground. Constanzo then cut his skull open with a machete. He removed Kilroy’s brain and placed it into the nganga, a sacrifice he believed would grant him intelligence and wisdom.

Ayala put the Hernandez brothers to work digging up graves, and even requisitioned a neighbor’s backhoe to aid in the dig. Eventually, they would exhume the remains of 14 more people. All of them had evidence of torture: decapitation, burning, castration, and in at least one victim, removal of his heart.

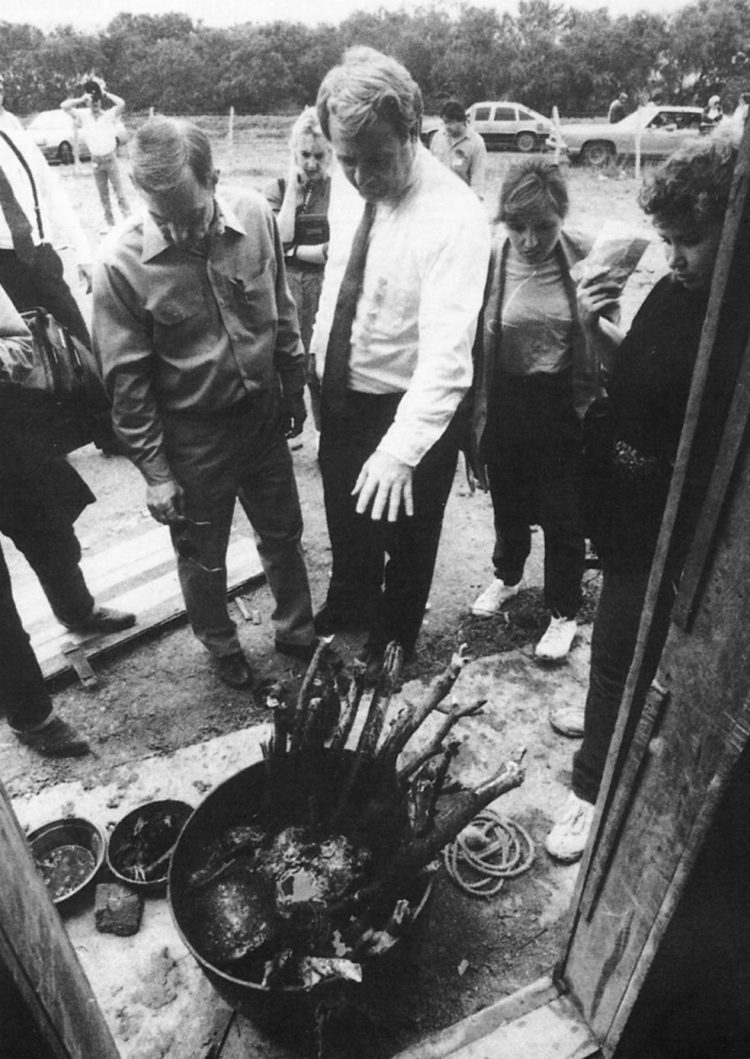

When police searched the shack, they found evidence that human sacrifice and mutilation had occurred there: a machete caked in blood and tissue; bottles and jars filled with a putrid mix of blood, hair, and other tissue; a 55-gallon drum apparently used to boil victims’ flesh off their bones. And of course, the nganga, which contained a stew of rotting flesh — both human and animal — including Kilroy’s brain.

Although police had the Hernandez brothers and a few other accomplices in custody, Constanzo was in the wind. Thanks to Serafín’s confession, police knew he would be traveling with Sara Aldrete, his high priestess and right hand.

Aldrete was not the type anyone would suspect of belonging to a murderous cult. She was an honor student at Texas’ Southmost College, majoring in physical education. She was known by all the other students as friendly, outgoing, and deeply involved in extracurricular activities. Yet the tall Mexican woman had been working with Constanzo for years, luring victims and recruiting new members.

At first, police feared the couple might have fled to the US. In the days before cell phones or widespread debit-card transactions, they were completely off grid. But police were able to discover that the two had been in the US, where they obtained fake IDs. They then drove to McAllen, Texas, and boarded a plane using their fake identities. Their destination: Mexico City.

Police searched Constanzo’s various homes and properties in Mexico City, but could not find the couple. By the end of the investigation, however, they would discover more bodies suspected of being killed by Constanzo, bringing the number of known victims to 23.

The police put up wanted posters and offered a reward. But weeks went by with no luck. So they went to a local anthropologist who specialized in Santería and Palo Mayombe. He suggested that they burn the shack, and most importantly, the nganga, to metaphorically smoke Constanzo out of hiding.

So, with a TV crew filming them, they did just that. The filthy shack went up in flames, and the nganga was dumped out and set aflame as well.

Constanzo — who was staying in a high-rise apartment with Aldrete and his current lover, along with two more of his followers — saw his nganga burned on TV. He freaked out, just as the anthropologist predicted.

When local police arrived at his apartment building on May 6, 1989, they were responding to a call about another disturbance. Constanzo, in a state of paranoia, began burning all his cash on the stove and flinging wads of cash and coins out to the street below. Seeing the disturbance, police turned their attention to Constanzo’s apartment.

Constanzo began shooting. The police returned fire. For 45 long minutes, the two sides exchanged gunfire. One police officer was wounded. Finally, Constanzo was shot dead. When police entered his apartment (#13), they found Constanzo dead of multiple gunshot wounds. His lover was lying next to him, dead from one gunshot wound. Aldrete was hiding in a bedroom, unharmed. She and the two other cult members surrendered.

A total of 14 of Constanzo’s cult members were charged with crimes ranging from murder, to drug-running, to obstructing the course of justice. Sara Aldrete, Elio Hernandez, and Serafín Hernandez were convicted of multiple murders and given prison sentences of over 60 years each.

While the Kilroy family was finally able to achieve closure, the families of Constanzo’s other victims didn’t have the benefit of two national police forces and media helping them. Of his multiple Mexican victims, only nine have been identified. Police still suspect there may be more victims who simply haven’t been found.