Hell seems to be a collective assault on the American imagination — the culmination of our entire post-Columbus cultural history and political infrastructure. Ask anyone familiar with it to describe the scene and you’ll likely get the same description across the board — a furnace of torture, suffering, demons and unfathomable pain. Hell is embedded into our lives, whether we believe in it or not. It’s a place mutually visited by every person’s imagination that has been exposed to an Abrahamic society. It’s a place we condemn undesirables to, a place we reference to instill fear and obedience, a place we devotionally protect our loved ones from being exiled to. For all our certainty of its existence, Hell is perhaps the least understood of places, even by the most studiously pious of individuals. Its assertion into our culture and conscience is a testament to our collective religious illiteracy. So why is it so vital we understand its origins, rather than blindly accept what we’ve been told about it? The latter method has, well, rarely worked in the favor of the common person throughout history.

Alas, Hell is real. Yes, that’s right. Or at least, it’s based off a real place — an ancient landfill to be exact. Although there is no mention of a “hell” in the Bible, it is based on an actual place. In Jerusalem, in the Valley of Hinnom, there is a large trash dump referred to in the Book of Matthew as “Gehenna”.

It was originally used by the ancient Israelites who sacrificed children and burnt their bodies to appease the pagan Canaanite god Molech. In Leviticus 18:20, God expressed his hatred of the false god Molech, and deemed the place unclean. Gehenna was eventually used as a landfill by the inhabitants of Jerusalem, where people took their trash to be burned. The place began to wreak havoc on daily life in Jerusalem. The smell of burning sewage, flesh, maggots and garbage wreaked absolute havoc on the inhabitants of Jerusalem, causing documented medical problems like nausea and breathing difficulty. Clearly, the place was unpleasant — frightening even — and thus it’s no surprise that Gehenna was used, and still is today, as a metaphor for the final place of punishment for the wicked. It was first used as a symbolic depiction of Hell in Mark 9:47. Gehenna was translated to Hell later, around 1200AD.

ENTYMOLOGY:

There is no mention of Hell in the actual New Testament, but there is in (much) later translations. So let’s dig into the etymology a bit. The modern English word HELL is derivative of an Old English word “hel”, or “helle”, first documented around 724AD to refer to the nether world of the dead from the Anglo-Saxon Pagan period. You can look at English translations (which have been heavily doctored according to the major events of their relative historical period) like the King James Version of the Bible (the most widely read version in modern United States history), which has 19 references to Hell, to be exact. Notably, verses such as Mark 9:47

“And if thine eye offend thee, pluck it out: it is better for thee to enter into the kingdom of God with one eye, than having two eyes to be cast into hell fire:”

Pagans were, ironically, executed at the same time their mythology was being plagiarized by their very executioners. Sacrifices and burnings occurred in Gehenna because it was strategically selected by ancient Israelites as a holy place, as opposed to just being some arbitrary dump in the middle of a lone valley. Furthermore, Jesus specifically refers to Gehenna 11 times in the New Testament, but not Hell (until later translations, of course). The Islamic version of Hell in the Quran is known as Jahannam, obviously later translated from Gehenna, as well.

The story of Hell as we know it — a place of fire, brimstone, punishment and sin — is first solidly referenced in the Apocalypse of Peter, an early Christian text published in the 2nd century AD. A first hand account written by Peter himself, he claims that Jesus took him on a tour of heaven and hell. What he saw was a place where women who “adorned themselves for lust, and the men who mingled with them” as well as liars, thieves, and anyone who denied God, suffered an eternity of torment in a place of fire. It’s important to note that the Apocalypse of Peter was edited out of the Bible later on and replaced with another similar apocalyptic text, the Book of Revelations. Some Biblical scholars will quite literally cite that Peter was a raving mad, bumbling old lunatic and thus his narrative was discredited with haste.

THE OLD TESTAMENT:

Stepping back further in time, examining the Old Testament — the foundational text of Abrahamic beliefs — there is the Hebrew word “sheol”, which means “the place of the dead” or “the grave”. Sheol is a neutral term and has no connotations of punishment. It’s simply the place we go to when our bodies stop working. In the Old Testament, the word is found in the Bible 65 times. There was no concept of the resurrection of Christ at the time, however, like Hell, this concept emerges later on after the Babylonian Exile.

The Babylonian Exile occurred around 587BC. This often overlooked event is vastly important to Biblical history, and it’s especially important to note that it occurred nearly half a millennium before Christ. Jews were taken into exile in Babylon, where they got to know the only other monotheists in the area — the Zoroastrians. Here, there was a cross fertilization of concepts and ideas that were borrowed and shared. This cultural exchange laid the grounds for the major Abrahamic religions, as we know them.

ANCIENT RELIGIONS & HELL:

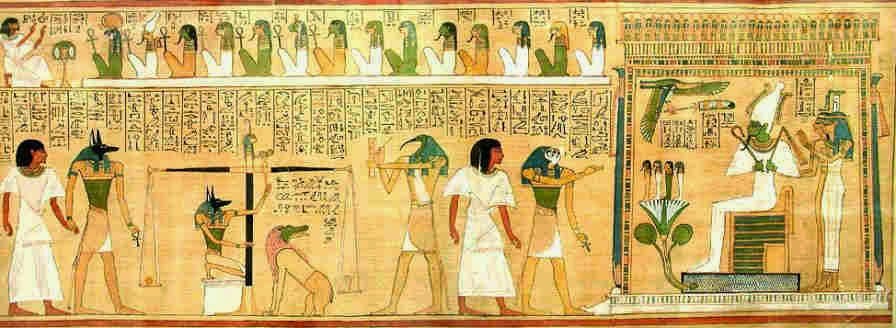

It’s important to acknowledge that the concept of a world one enters after death is not original or unique to early monotheists. The ancient Egyptians had a place called Duat referenced heavily in their Book of the Dead. Maps of Duat were often inscribed on the insides of coffins and sarcophagi to help the deceased navigate the underworld. It is the underworld where violators of the law are condemned, as well as a host of mythological activity. According to the Book of the Dead, the sun god, Ra, goes to Duat every night to battle Apep, the god of Chaos. The dead who enter Duat must travel through various “gates” guarded by anthropomorphic hybrids of human bodies with various animal heads. These gatekeepers were ferocious and vile. For evidence, one need not look beyond their names. Guardians of the Gates of Duat had charming titles like “One Who Eats the Excrement from his Ass” and “Blood Drinker who Lives in the Slaughterhouse”. Should the deceased successfully pass through the gates, they faced one final test. Ma’at, the Goddess of Truth and Justice, carried out the “weighing of the heart”. During the weighing, the heart of the deceased was placed on a scale, with a feather on the other side. If the heart was heavier than the feather, it was eaten by Ammit, the Devourer of Souls. Those lighter than the feather were allowed to pass to the “eternal paradise Aaru”. This is the first documented human narrative of a judgment of souls by a deity, and the binary separation of place where a soul may wind up depending on their deeds in life.

There is similarly an afterlife in ancient Mesopotamia, although it lacks the literary oomph of its Egyptian counterpart. The afterworld is the same as one’s life on Earth, but… duller. There is no pain or joy to be experienced. Just lonely, aimless wandering through the rise and fall of the sun and moon each day. There is also the story of Inanna, the Sumerian goddess. In it, Inanna goes down to the underworld and at each of the 7 gates, she must shed one piece of clothing. When she reaches the final gate, she is naked. Ersehkigal, the goddess of the underworld, is conveniently guarding this gate. Ereshkigal becomes angered by Inanna showing up naked to her doorstep, so she kills her and hangs her corpse on a post. After her body hangs there for three days, the Gods decide to rescue and resurrect her. Sound familiar?

In ancient Rome, the underworld is described in a poem of Virgil as a place full of flaming rivers, with triple-thick walls to prevent sinners from escaping, black gates guarded by Hydra (a sort of giant dragon with 100 heads), and the goddess of revenge who sits a top a tower with a whip lashing the sinful populace that fills its dark caverns.

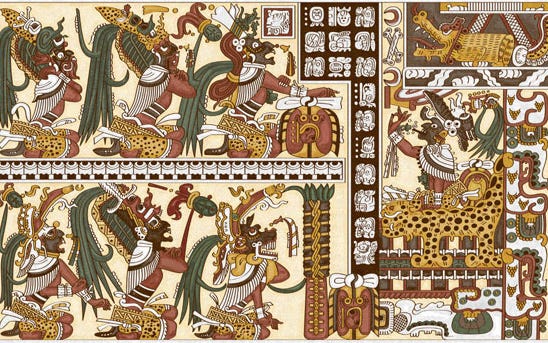

The ancient Maya also had an underworld, Xibalba, as described in their sacred text the Popol Vuh. Similarly, Xibalba had various “houses” one had to travel through that challenged the deceased’s soul. Places like the House of Jaguars (filled with hungry jaguars), the House of Shrieking Bats (self explanatory), and the Sharp House (full of razor sharp objects one must crawl through), and curiously enough, a House of Fire.

There is a plethora of similar underworlds that spans across what seems like every human culture. What is fascinating is not only the several thousand year long cultural exchange and game of telephone that we can trace in these religions via their texts and traditions, but how the concept of a place we go to after we die to face judgment and consequential punishment — a place of fire and torment — has developed in human communities completely isolated from one another. As the Bible was being written and rewritten, thousands of miles across the Atlantic ocean, ancient peoples of the Americas explored the realms of Xibalba. Whether strange coincidence or indication of some greater phenomena of the human mind, it’s clear that no singular underworld holds the sovereign authority over all people after we die.

If so much of our public policy is weighted on the words found within the Bible — the alleged words of God himself — it is troubling that we digest the heavily processed and filtered versions of them with such ease and lack of skeptic inquiry. It is imperative to our progression as a species that we understand the origins of our belief systems and the role they play in the human psyche — to instill obedience to the status quo and dissuade any violators with the fear of an eternity of suffering.