When it comes to exploring what the human body can mean and do in the context of art history, it’s hard to beat performance art for its versatility, emotional impact, and sheer strangeness. These works, each excerpted from Phaidon’s new book Body of Art, are some of the most famous examples of contemporary artists transgressing the agreed-upon limits of safety, sanity, and decency in order to reframe our everyday lives through the prism of aesthetics. Though the results are often visceral or even repulsive, each performance speaks back to the so-called “normal” social conditions most of us barely notice.

This feature was taken from ART SPACE!

Click here to learn more about Phaidon’s Body of Art and buy the book.

1ST ACTION

Hermann Nitsch

1962

Hermann Nitsch (b.1938) and the Viennese Actionists sought to liberate aggressive instincts through ritualistic performances, slaughtering animals, and extreme tests of the human body’s endurance. In the first of a series of taboo-breaking “Actions,” Nitsch, dressed in white linens as if a priest, had himself tied-up in a cruciform position in the apartment of fellow Actionist , Otto Mühl (1925–2013), and then had Mühl pour animal blood over him. The work recalls both Christian liturgy and pagan blood rites. The body had long been subject of Christian art and ritual, for example, paintings of martyrdom, or the red wine transubstantiated to blood in the Eucharist. But in addition to symbolism, which could have been conveyed in any number of mediums, Nitsch’s performance also afforded the artist a direct and visceral experience. Nitsch’s interpretation of Freud, who observed how the repression of aggressive and sexual drives in society, could lead to neuroses for its members, also inspired his Actions. Freud noted that recalling a repressed trauma could help release emotional tension, a process called “abreaction.” Nitsch thought of his Action as an Abreaktionsspiel (abreaction-play), hoping his corporeal gesture would offer a cathartic release of those instincts for himself and his viewers.

VAGINA PAINTING

Shigeko Kubota

1965

Vagina Painting was performed in July 1965, just a year after Shigeko Kubota (b.1936) relocated to New York. Having been active in avant-garde circles in her native Japan, Kubota was invited to New York by George Maciunas, one of the founding members of Fluxus, a group centered on performance and experimental art. Fluxus members sought to collapse the maker and viewer, art and the everyday, through action, performance, and play. Vagina Painting stands as an iconic Fluxus performance and has been interpreted as a key moment in feminist art; although Kubota herself denies its feminist import. During the performance, Kubota squatted over white paper spread out on the floor, creating gestural strokes via a paintbrush attached to her underwear, each linear mark an index of her bodily movements. The brush was dipped in red paint, in a deliberate evocation of menstrual blood. Equally deliberate, however, was the association with distinctly masculine modes of creativity such as the Action paintings of Jackson Pollock (see p.412) or Yves Klein’s “Living Brush” works (see p.289), as well as traditional Japanese calligraphy. Vagina Painting was one of several performances by female artists in the mid-twentieth century that emphatically utilized the body, co-opting corporeal performative actions, then coded as male, and deliberately subverting them.

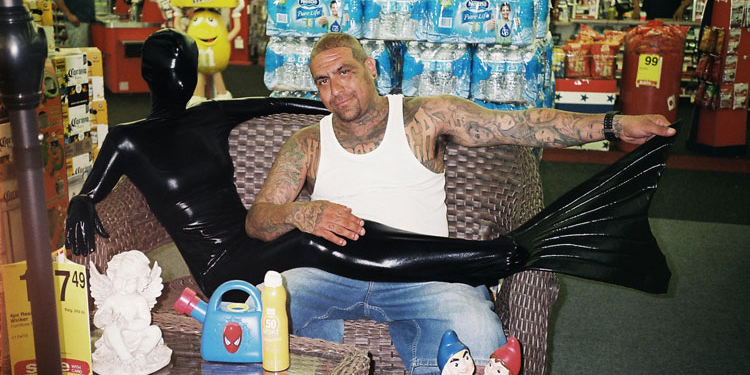

THE MAD DOG, OR LAST TABOO GUARDED BY ALONE CERBERUS

Oleg Kulik

1994

On a freezing late November night, Oleg Kulik (b.1961) staged his first ‘mad dog’ performance outside a small gallery in Moscow. Stripped naked and wearing a chain leash held by his ‘owner’, the artist growled and barked at passersby. A crowd soon gathered, laughing, and taking photographs. Suddenly, with savage ferocity, Kulik bit a complete stranger. He then ran into the traffic, jumping onto a car, and throwing himself at the windscreen. Kulik’s unpredictable and often frightening actions were a kind of shock art, forcing the viewer to consider his own animal nature, and vital instincts. Symptomatic, perhaps, of a pent-up artistic spirit freed from Soviet restrictions, Kulik has often performed with animals (including goats, cows, cockerels, and birds), protesting at the hubris, and anthropocentrism of human culture. He is perhaps best known for the scandal he caused at the opening night of a Stockholm art show in which The Mad Dog was an exhibit. Chaos ensued after he attacked and bit a man who had ignored the “dangerous” sign posted next to his “dog house”, before running riot over several artworks.

BARBED HULA

Sigalit Landau

2000

An activity usually enjoyed by children for fun, or by adults for fitness, hula-hooping gained widespread popularity in the 1950s, and typically involves gyrating the hips in order to keep a hoop elevated around the waist for as long as possible. For Sigalit Landau (b.1969), the action takes a disturbing turn, as we see the torso of the naked artist rotating a hoop made from barbed wire. Over the course of the film the camera moves closer, revealing the extent to which her skin is torn, and bleeding, and still she twists, without making a noise – the only soundtrack the gentle lap of the waves. The video was shot on a beach in southern Tel-Aviv, and in it the artist makes a connection between the geographical boundary of the sea – Israel’s only natural border – and the skin as the body’s boundary. In a nation where religion is central to daily life, the action brings to mind rituals of self-mortification undertaken for spiritual reasons. The work also references a lineage of ceremonial–cathartic body art practiced since the 1970s, in which artists have used their own bodies as a medium to explore broader political, social, and sexual issues, often enduring discomfort or pain.

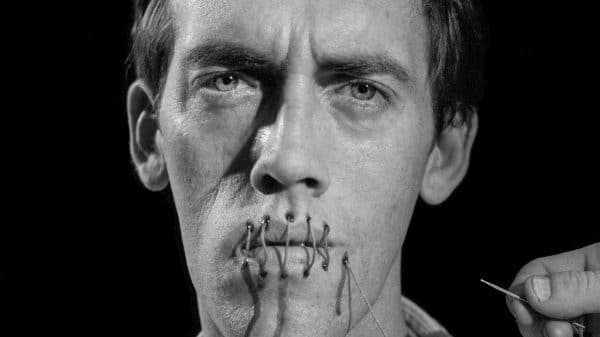

INCORRUPTIBLE FLESH: MESSIANIC REMAINS

Ron Athey

2013

Messianic Remains is the third performance in Ron Athey’s (b.1961) “Incorruptible Flesh” series, which began in 1996. Athey, who is HIV positive, began researching saints, martyrs, and others with “incorruptible” bodies (believed to be immune to decomposition, a sign of holiness) as he watched his friends struggle with the impact of AIDS. Raised by Pentecostal Christians, Athey enacts rituals such as anointing the sick, and a belief in the body as a site of transformation or resurrection, much to the ire of American religious conservatives. His work examines the limits of pain: the physical pain of masochism and disease, and the psychological pain of surviving an epidemic. Tattooed, naked, and bearded in the style of an ancient Egyptian, Athey is strapped to a metal rack resembling a medieval torture device. Hooks in his cheeks and eyebrows pull his flesh towards the cross at the head of the rack, and a baseball bat protrudes from his anus, suggestive of sexual violence. Reflecting the anointing of Jesus by Mary, the audience is invited to rub a foamy substance into Athey’s corpse-like body, which is spotlighted. He then rises in the midst of a funeral procession inspired by Jean Genet’s 1943 novel Our Lady of the Flowers, a mostly autobiographical account of a homosexual man’s life in the Parisian underworld.

EL PESO DE LA CULPA (THE BURDEN OF GUILT)

Tania Bruguera

1997–9

In the late 1990s, Tania Bruguera (b.1968) begana series of highly visceral, metaphorical performances that commented on the history of the Cuban people and contemporary guilt felt about the nation’s foundation, during which the island’s native population was eradicated. The Burden of Guilt is inspired by a story of the collective suicide of a group of indigenous Cubans who in an act of rebellion against their Spanish oppressors ate dirt until they died, literally consuming their own ancestral land and gaining ownership over the destruction of their culture, heritage, and bodies. Bruguera re-enacted this solemn gesture, rolling dirt mixed with saltwater, symbolizing tears of sorrow and regret, into small balls, and slowly eating them over several hours in an act of penance. She appeared naked except for the carcass of a slaughtered lamb hung from her neck, at once resembling a shield, a gaping wound, and a sacrificial offering. Brugera’s work examines fundamental questions of power and vulnerability in relation to the personal, political, and collective body, and typically features the artist performing physically demanding rituals. Having relocated from Cuba to the USA, her early work involved restaging of corporal performances by another exiled Cuban artist, Ana Mendieta.