What time is it? It’s time for y’all to check out this amazing TENSION SPAN interview. This band has created one of my favorite Post Punk records of 2022, The Future Died Yesterday.

Label: Neurot Recordings

Take us back to your childhood—what music did you hear around your home, booming out of the cars in your hood, or in your headphones?

Noah: At a very early age, I was searching out all things rock and roll. Anything weird and different. Anything I could get my hands on. But I grew up in Oakland, CA, single-mommin’ it with my sister Dana. Often the only white kids on the block, we listened to a lot of popular Black music, Earth Wind and Fire being an absolute favorite of mine.

There are just a few short years when everything moves so fast as far as music and youth culture goes, and it seems like just a year or two from when I was listening to Saturday Night Fever, to Kiss, to Blondie and the B52s, AC/DC, Motörhead, until finally Dana and I found punk. It was a small tight-knit scene but we found our way in. Universal Records was on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley and I spent a lot of time there just being in the room with the older punks, listening, paying attention to what was awesome, what was new, what was about to happen. I bought TSOL and Bad Brains records. We had Fang and Flipper and Intensified Chaos and Special Forces and Social Unrest — all amazing local punk bands. We had Ruthie’s Inn where we saw so many bands who came through town. The Mab and the On Broadway were just a late-night bus ride away. These were intense shows, it was a very chaotic and often violent scene. Chaos and violence actually defined the scene back then.

It wasn’t until a few years later when the Gilman Street Project emerged that the scene had an ethic of being inclusive and youth-friendly. But back then, it was just a mix of kids like us, runaways, skinheads, and some absolute scumbags and junkies. A very tricky terrain to navigate.

Geoff: I am a few years younger than Noah, but I grew up in suburban Southern California in the late ’70s/early ’80s and was exposed to Punk and ‘New Wave’ at a very early age, like 7-8 years old. My older brother was into these scenes, so I have very early memories of sitting around listening to Ramones, Sex Pistols, Damned, Buzzcocks, etc records. Although being so young, I didn’t quite understand what Punk was about other than that it was confrontational and a provocation directed at more conservative-minded people. Probably because I was just a little kid, I was really into some of the more quirky and weird New Wave bands of that time, and was given copies of the first B-52’s, Oingo Boingo, and Wall of Voodoo records and listened to those records over and over.

Later on, I realized that there were only a couple degrees of separation between some of the people that were involved with the early LA punk scene and the people that I was exposed to….just a weird coincidence of the location and time, really. I was taken to see a Ramones gig at the Hollywood Palladium when I was 11 years old and that was an eye-opening, inspiring (and slightly terrifying) experience. It’s not that uncommon nowadays to see kids at gigs, but at that time…no way. Looking back on that, I can’t believe that the venue let a small kid into a gig like that, given how that scene was in those days. Around that time I was also getting into Skating and started to discover Hard-core punk through other skaters and early Thrasher magazine articles, and a few years later started going to shows in the LA area somewhat regularly from the time I was about 14 onward. I saw a lot of gigs at the Country Club in the San Fernando Valley…notoriously ultra-violent things happening regularly at that time between gangs of skinheads, Suicidals, and punks. Then I started going to more underground gigs of various sub-genres of punk, hardcore, etc throughout the late ’80s into the early ’90s in San Diego, OC, LA, and Santa Barbara, eventually moving to Oakland in the early ’90s.

Mauz: I am also a few years younger than Noah, and like Geoff grew up in suburban Ventura County (from the mid-70s to 1984). We actually lived about 10 miles away from each other back then but didn’t meet until both of us moved to the Bay Area in the 90s. My mom had a big record collection and immersed me from day one with all of her faves: Beatles, Stones, CCR, The Doors, Little Richard, Fats, Sam Sham and the Pharaohs, Diana Ross and the Supremes, Otis Redding, lots of Motown and Stax, loads of blues, early folk, lounge, soundtracks, the list goes on and on. Probably standard fare for many, however, she was a lot older than most of my friends’ parents (born in the mid-30s, “The Silent Generation”) and she always seemed to have her ear to the ground with new music for someone her age. She was the one who turned me onto The Blasters, who she loved, since they were a punk throwback to all the music she dug in the 50s. Kind of surprised she never got into X or Iggy and the Stooges actually. I inherited her record collection a few years ago after she passed and still discovering all sorts of cool records I never knew she had. Aside from her, I got turned on to loads of 70s rock and disco stuff from my two older half-sisters, who would stay with us on weekends. They often were bringing me records: Kiss, The Who, Sabbath, The Steve Miller Band, and Heart, to The Commodores, Donna Summer, etc. From there I was hooked with anything I could find on the radio, first via AM radio in the 70s (The Mighty 690) and soon after the hard rock/metal stations in LA (KMET / KLOS) and KROQ in the 80s when they mostly played new wave and punk. Got deeper into punk thru skateboarding and listening to Rodney on the Roq in junior high around 84-85, there was no turning back for me at that point.

Give us the science behind the title and artwork of your new record, The Future Died Yesterday?

Noah: Well, the title track was one of the first songs I wrote for this project. Geoff and Mauz wrote the music, and I poured myself into the words. It was sort of like breaking through a dam of thoughts. If you really read it and follow along it will make perfect sense to you — there’s a feeling of being separated from the society we are surrounded by. None of it feels right, compassionate, or kind. It’s actually quite brutal, and that brutality is rewarded. As is self-absorption. There’s a way that it pulls you apart, and what’s left is fear and stress, and anxiety and depression. Insanity is another word for it, really, the long-term effects of this type of existence. And the more you try to make sense of it and try to find some meaning to any of it, the more discouraging and meaningless it feels. Sorry, that sounds so dire, but that’s what this song is about. There is some hope and humanity in there, but that’s pretty much what this whole album is about.

The cover artwork was done back in the early 1990s by our friend Neil Grimmer. He played in a band called Paxton Quigley. It’s a stencil of a lie detector test. I think we were all influenced by stark and strong imagery that you might find on Crass albums and the whole family of bands that came from that world, Dirt, Zounds, Conflict, Antisect, and Rudimentary Peni, who for many of us was at the top of that totem pole. Finally punk had an intelligent voice and a community of thinkers and activists. It felt very empowering to be a part of this punk scene. It still does. But there was something especially inspiring about it when you’re witnessing its emergence, bands from all over the world. Art, music, activism — also anger, rage, and nihilism. I think that’s the context that the artwork comes from. Just thinking about it now, the lie detector test is actually a device used to measure stress and fear and anxiety, so that folds in conceptually quite well. I know we made this album in 2022, but a lot of the thought behind it and the art aesthetic comes from an earlier time, the dark punk of the mid-’80s and the way the scene expanded through the early ’90s. Strange how relevant it all feels today.

Geoff: I think Noah’s response explains it well. Neil Grimmer’s stencil art was a significant part of the aesthetic of some parts of the early ’90s Oakland scene, from t-shirt graphics to seeing these stencils spray-painted on walls and sidewalks around town.

In addition to Noah’s observations about what a lie-detector device is actually measuring, the image immediately struck us as the perfect image to represent the moment that we were all in, socially isolated by the pandemic and spending inordinate amounts of time doom-scrolling through a sea of mainstream media coverage and social media posts, a significant amount of it being pure propaganda crafted by either MAGA paleo-fascists seeking to demonize those who were protesting against police-terror and the savage economic conditions or neo-liberal techno-fascists trying to gaslight the proles into endangering their lives to ‘keep the economy functioning’ during a global pandemic event.

At the very least, I think Punk provided all of us with highly-calibrated bullshit detectors, so I think that this image can also represent something positive and empowering as well. While it is an oversimplification, to me, Punk was always about telling the truth, rejecting greed and shallow self-interest, and taking care of each other, to the best of our abilities to do so.

If you could put three of your songs from The Future Died Yesterday in a time capsule to be opened 25 years from now, what songs would you put in there, and why?

Noah: Heck, I don’t know. I think the title track is a substantial song in terms of its message and the music, driving and strong but also contains a thoughtful complexity in what it’s expressing. I do want to point out the irony of preserving a song in a time capsule called “The Future Died Yesterday.” Beautiful actually, I like it.

There’s a song on the album called “Human Scrapyard” that I would include because it tells the story of something very important and relevant and worth remembering that this is what is happening right now. The number of homeless people in our country has escalated to unforeseen and unimaginable numbers just in the last 5 years. There are tent communities all over this country that didn’t exist before. There is no safety net to catch people who have fallen on hard times in this country. I often think about how each and every one of us is only one slip-up away from living on the street. There is a serious mental health crisis in this country which is a recurring theme of this album. Not everyone can keep their footing in these difficult times. My heart breaks for them. I feel for them deeply. This country generates so much wealth for so few people and there is no substantial effort to reach out, to reach down, to help those who have fallen on tough times. It’s disgusting. It’s inhumane. And even our little punk rock fucking song about it should probably be preserved, to tell the truth about it. Well, all of that might have sounded a little self-important, but that’s a strange question you asked.

The third song I would put in a time capsule is a song called “Didn’t See It Coming” which is just a more human and introspective take on the state of things that I think most of us can relate to, especially if you happen to be someone listening to music like this, from underground self-proclaimed punk poets. Ha! It hits a universal chord — we are all standing and falling. We are all climbing and crawling, doing the best we can given the conditions we are moving through every day. Again, I understand why people fall off the path. We are so far from the illuminated one that we were meant for — Kindness, compassion, one that celebrates our shared humanity. At this point in an interview, it may start to sound like dribble but, since you asked, these are the thoughts I feel like sharing today. I appreciate your readers’ patience and attention.

What was the creative process behind the song “Filaments”? The opening riff is sublime! What kind of emotion did y’all want to evoke with this song?

Noah: The riff is unlike the rest on the album, so I appreciate you pulling that one out. It’s kind of rolling but also confident, and with a slow enough tempo to invite a contemplative mindset. When I was young I read a quote in a book that was a collection of writings from punk philosophers. This was written by Tomas Squip who was the singer of a DC punk band called Beefeater. He wrote, “I believe in the Sun that gives light, the moon that reflects light, and all the little flames.” I think about this quote often. All the little flames are me and you and him and her and them. We are the little flames. Each of us carries a filament that burns inside us. It’s where our passions come from, or love and friendships. That’s what this song is about. We are all entangled. We are all connected. This is the great equalizer, no matter what we may be having or lacking in the material world, there is this thing that connects us. I guess you can call it a soul. But it’s the part of the soul that activates us in our daily lives. To be engaged and engaging. I think it’s an important thing to recognize in each other and in ourselves.

Geoff: When I was writing the main structure of that song, I was mainly trying to make something that was heavily influenced by early 70’s krautrock, particularly Neu! and Michael Rother’s solo stuff. I love that stuff because it has the expansive and meditative qualities of weirder psych and the driving energy/momentum of high-energy punk. That era of krautrock is, to me, the missing link between the psychedelic rock of the ’60s and the Punk Rock of the mid-late ’70s. I sent those tracks to Mauz and he came up with those brilliant bass lines that both enhanced the motoric vibe but also introduced some elements of the UK anarcho/peace-punk sensibility (of which I am also a huge, huge fan of).

Tell us about the sentiment of the song “The Future Died Yesterday”?

Noah: I explained a lot about this song above, but I will elaborate on one thing here — the search for meaning. This has been a recurring thread in my life, when dealing with my own history of mental health challenges, addiction, anxiety, and depression. I continue to ask myself, What if all of this is merely a “human construct” and we’re being led along by this phony notion of “finding happiness”? What if it’s all fake? Why do we wake up and go to work? Why do we do anything? Why do we feel so flawed for feeling sad? What am I missing? Why do I look at this life and feel like I’ve been duped? Like it’s all a veil, a cover-up for the reality of the absolute nothingness it conceals?

Here’s the problem — if you go down that rabbit hole, searching for meaning, and you get all the way to the bottom, and you find nothing there, well now you’re sort of fucked! The only positive reframe I’ve managed to come up with is that we are all in this fake shit together. So we can find our like-minded people and celebrate our rejectionist stance together. And be real about it. That’s what punk rock is to me.

Describe Tension Span’s sound as a weapon of mass change or a superpower—what impact do you want to see it have on culture or our society?

Noah: Well, I’ve been making heavy emotional music for a very long time. I don’t see it as a weapon of mass change. I see it as a circle that invites you in. If it’s a sound and a feeling that you resonate with, then it’s a circle you belong in. Sometimes it can inspire, or comfort, or shake you up or break you down or express your rage. It can do all of these things. It can make you think. It can make you cry. I don’t see it as a weapon, I see it as a healing, like a shared medicine for our emotions. Maybe that’s a superpower. It certainly is powerful.

Tension Span I think of as thoughtful, sometimes brooding, sometimes driving. There’s a layering thing we do where there’s a lot going on and if we dial it in just right, there’s a harmony to it all, or a single resonance that our music creates. Even if it’s built on found footage of someone’s real heart and story that we build the song around like “I Can’t Stop the Process” or something horrific that reflects a very dark thread in our humanity like “Covered in His Blood.” Mauz and Geoff put those together and I think it’s brilliant. It’s a collage of sounds, words, music, and voices, speaking their own truth and it’s fucking terrifying.

Describe some of y’alls favorite shows at the New Method Warehouse?

Noah: New Method Warehouse was an important place for me. I went to nearly all of the shows there, as they were collectively put on by the folks who lived there, which included members of Christ on Parade and Neurosis. Most of the people there were on rent-strike and it was a true act of activism the way they took this place over and used it for their own homes, art spaces, and also a place for punk bands to play. The shows were only shared word-of-mouth. We made flyers and handed them out, but it was really for the people who were looking in the right places and who saw it as something special and different from most shows in the little punk clubs.

I remember one show where they knocked a huge hole in the wall and took over the space next door that was locked so we could fit more people and have more space. The Melvins played there before their first album was recorded. Corrosion of Conformity was amazing. The band Beefeater that I mentioned played upstairs in the room with the giant hole in the wall. Operation Ivy, when Jesse Michaels and I were still in high school. These are just a few that come to mind, but there were so so many great shows there. Great bands, diverse bands — it was a really thriving music scene. There was a feeling at these shows that we were all in this together, making this happen together, and a feeling very early on that what we were doing was special.

Now, nearly 40 years later, with the benefit of hindsight, I think it’s safe to say it WAS special. I can’t really see anything happening quite like that again. So many bands came through and played that place who are still very much revered and important. It really was a cultural movement led by young activists and anarchists and artists. The last thing about it that is worth noting, and someone older than me can check my recollection of this — there were great bands that lived and practiced at New Method before Christ on Parade and Neurosis — The mighty Crucifix was there, and Fang and Flipper as well, I believe. We were the last group of young radicals to use it as a performance place, not the first. Alas, the building was torn down long ago.

Why do y’all feel that the Bay Area played such an important role in the American Peace Punk movement?

Noah: When I was in high school, I really admired this young kid named Jason Ellish. He was the drummer of 80′s Post Punk Lost Treasure:

TRIAL Moments Of Collapse LP Stream”>Trial, who was kind of the most artistic and cool of that group of bands in my opinion. I made the mistake of calling him a Peace Punk and he made it very clear that I was labeling him and I should not do that. Ha! So keep that in mind!

I think there was just a certain collection of people in the Bay Area, involved in Punk but also involved in politics and activism for Animal Rights, Food Not Bombs, groups like this that really required information access and some basic facts and education to be spread in order to change some of the horrific things that many people just accepted as a normal way for the world to be. So there was definitely idealism and the bands really poured their hearts and souls into this effort. Of course their art, their music reflected the message. Some might say the music sounded a bit depressing, but let’s be real, there was a lot to be depressed about!

The people I know in this scene were some of the smartest people I’ve ever met. Creative and dedicated. It was inspiring to witness young people with hearts this big and an earnest desire to change society for the better. There was another amazing band called Atrocity. There was a group of siblings who were pretty exceptional in their contributions to our little scene at the time. John Barruso was the singer for Trial. His sister Sarah Barruso sang in Atrocity, and their brother Matt Barruso played guitar in Crucifix. Sorry, I think I’m rambling now, but those were important years for young me. I was super inspired by that movement. Instead of punk being a negative reaction against so many things, this was punk being a positive reaction for change. It may not be totally obvious in our sound, but there is a real thread that connects the music of Tension Span with these bands, primarily I think in terms of how thoughtful and complex their message was and how that defined their music.

Mauz: I feel like I should mention there was also a smaller but pretty active Peace Punk scene happening in Southern California in the 80s and 90s that both Geoff and I were loosely connected with. LA had some important peace punk bands in the mid-80s: Iconoclast, Diatribe, Another Destructive System, and Final Conflict to name a few. Most of them were before my time but I did catch Final Conflict quite a bit when I started going to gigs in 87. Around then there were a whole bunch of new peace punk/crust bands that had formed: A//Solution, Apocalypse, Confrontation, Garblecrat, Glycine Max, and Media Children to name a few. There were loads of benefit gigs, unity picnics, protests, and anarchist gatherings. There were a few Food Not Bombs chapters popping up in Long Beach and other areas. All of that was very eye-opening for many of us and instilled some pretty powerful ideas and beliefs that still resonate loudly with me to this day.

The late 80s/early 90s were in some ways a low spot for some punk/hardcore bands at the time. Lots of classic HC bands were going new wave or melodic/pop-punk (7 Seconds, The Brigade), Crossover (DRI / COC) or Glam (Discharge / Junkyard), and all of the crazy and inescapable violence at gigs that Geoff mentioned earlier. Yet there was all sorts of new energy happening in bigger cities across the states. Profane Existence in Minneapolis, Squat or Rot in NY, Hippycore in AZ, the SoCal/Portland/Seattle scenes, etc. I think the Bay Area might have had a stronger presence due to the long history of punk networking here (MRR, Gilman, Epicenter/Blacklist, Mordam, The List.) All of these projects were happening within a 10-mile radius. It may be that it was easier for them to function and thrive in this region with the enormous connections and history that carried over from the 60s counter-cultural movement in the Bay a few decades previous… or maybe there’s something in the water here? I’ve been living up here now for 26 years and still digging it immensely…

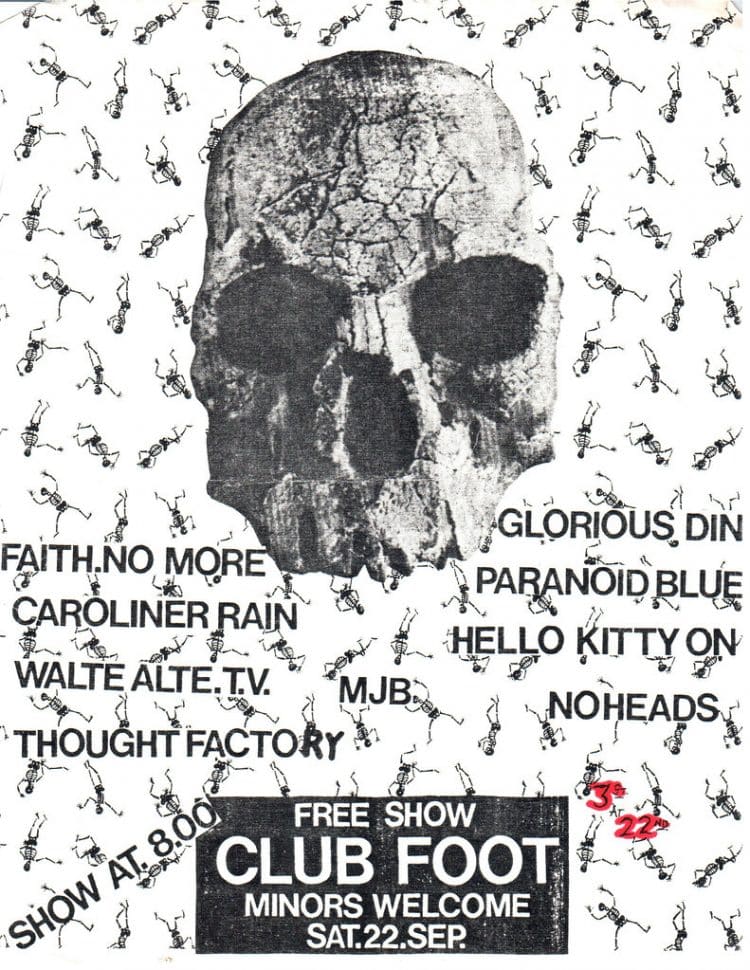

How did seeing bands like TRIAL, Glorious Din, and early Faith No More (I’m assuming you might have seen them at The Club Foot) impact the way you create music to this very day?

Noah: I went to a lot of shows at the Club Foot. It was a tiny punk club by the waterfront in San Francisco with distinctive roses painted on the walls that you can recognize in old band photos. In fact, Neurosis played their first show ever there in 1986. I still have a cassette of it somewhere. The three bands you listed are very different sounding bands, right? It’s a perfect example of how varied punk shows used to be. In the long history of underground punk, there were certainly some eras when punk shows were more uniform, or formulaic, the way hardcore sort of redefined it as fast and aggressive and, relatively straightforward musically, believe me, I love hardcore, but there have been times like that when you would get a crazy mix of bands that all sounded completely different, art-punk, noise, psych, punkrocknroll, deathrock, whatever — shows like that were amazing. It’s fun to see flyers for shows like that online. I don’t want to sound like “back in my day” about it because I’ve witnessed shows like that much later in different eras of the punk scene. The famous Gilman Street venue in Berkeley, for example, seemed to make a deliberate effort to welcome and celebrate very eclectic, diverse, and creative bands. But that’s a whole different road to go down, perhaps another time.

Do y’all remember the Summer of Hate in 1984? Does it trip y’all out that 38 years later we are still facing the same issues with racism?

Noah: Yeah, that’s pretty well said. It saddens me. The racist skinhead violence at punk shows in the mid-eighties, in particular, was scary as fuck. A lot of punks were violent and scary back then too. My young idealistic eyes saw some really horrible things — beatings, maimings, stabbings… I don’t want to honor any of those assholes by naming them, but we all knew who they were and we kept one eye on them at every show. You had to pay attention in a very specific way so that you weren’t caught in the path of something insanely brutal that was about to go down. I was 15 years old during the Summer of Hate, and I was pretty small for my age with a big Jewish nose, but was usually able to position myself behind bigger humans when the shit went off. But not always. I went to LA with Conflict around that time and violence at the Olympic Auditorium and Fender’s Ballroom was fucking real as shit. But yes, we certainly had our own cast of bad guys in the Bay Area. A lot of them were runaways living on the street and they saw the punk scene as an opportunity to wield some power.

As you said, it trips me out that racism is so flagrant and expressed so openly today. It’s easy to blame one orange asshole for opening the gate, but the truth is much darker and harder to swallow — people choose what to believe for themselves, and their behavior is driven by that choice, and in this country, racism is like a plague. A different kind of epidemic that takes over people’s hearts and minds. It’s heartbreaking. I don’t really know what else to say about it at this moment. To repeat an earlier point, it’s an opportunity for like-minded, kind, compassionate, good-hearted people to find each other and build our own communities through art, music, punk, philosophy, and sharing. Thank you for taking the time to read all of this.