REVIEW

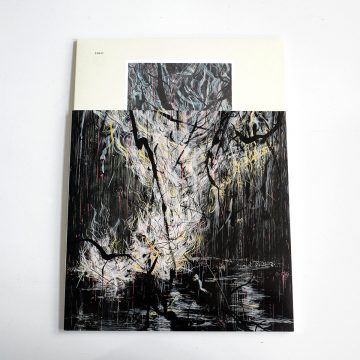

Love is what makes us human. It guides our decisions, shapes our worldview, and defines our experiences. Its absence spells tragedy, while its presence fills our lives with meaning. This is part of what Sumac’s latest album, Love in Shadow, wants to tell us. In its four tracks, due for release by Thrill Jockey on September 21, Aaron Turner (Isis, Old Man Gloom,Mamiffer), Nick Yacyshyn (Baptists), and Brian Cook (Russian Circles, These Arms Are Snakes) continue their musical experimentation. Kurt Ballou spent five days at Robert Lang Studios in Shoreline, WA recording the album live with the goal of keeping overdubs or fixes to an absolute minimum. The result is an album that sounds much more alive and human than the standard computer grid-built, mechanically perfect metal record. After their collaboration with Keiji Haino, Sumac’s sound has become even more spontaneous and unpredictable. Love in Shadow begins with the postcore-infused “The Task,” where mathcore syncopation broadens into jazzy sludge with untuned guitar. Sumac successfully attempts to bring through the feeling of immediacy of a live set. Most striking in “Attis’ Blade,” is its incessant, weighty rhythm track, which props up Tuner’s frenetic guitar pyrotechnics. An almost trancelike bass takes center stage in “Arcing Silver,” underpinning mathematical, quasi-surgical guitar riffs. The album ends with “Ecstasy of Unbecoming,” where Sumac indulges even more fully in its experimentation with dynamics. Love in Shadow is a highly mature work by a band that continues to shatter every musical boundary.

INTERVIEW WITH AARON TURNER

Claudia X Valdes

Love in Shadow, your new record, will be out in September 2018. Can you please tell us more about it?

That’s a pretty broad question. I can tell you that it feels, in some ways, like a very difficult record. It was fairly easy to write as far as all the basic arrangements are concerned but every step after that has been more complicated. And I think some of that has to do with the subject matter and a lot of the things that I chose to write about. Also, the process of working on it as a band was a bit difficult. I think all of us enjoyed the process but were also confused by it, partially because it was a lot of material. There are the four songs on the record and then we actually recorded another almost 20-minute song at the same time. So it was a lot of material to absorb and we did it, as we often do, in a very short period of time. For me anyway, there was a lot of psychological and emotional turbulence while making the record, and I think I may have to spend some years digesting it before I have any true perspective on it.

You are always searching for a new approach. What is the challenge for Sumac in this new record?

I think the challenge is finding a balance between taking risks and also having confidence in the work; feeling like we’ve done something that’s interesting and hopefully fulfilling for the people that experience it but also that isn’t just a recreation of what we’ve already done and also isn’t just some kind of sprawling mess that doesn’t really make any sense. And that’s not an easy thing to try to assess, especially when we’re doing things on such a short timeline. As I was explaining, we work in very short bursts because we all live in different places and it’s hard for us to gather all together. So we don’t have a long time to let the songs develop on their own. And, in a way, I think that’s good because it means that the process is often driven by intuition and very spontaneous. At the same time, I know that there are parts of every record we’ve made where we wished we had a little more time to play at and get comfortable with. In the end, though, I think it’s a worthwhile tradeoff because I’d rather have a song still feel fresh and retain its mystery than have all the original vitality sucked out of it by just going over it and over it again. So, I think the challenge for Sumac is to do something new and to take risks and also to feel like we have done the best that we could while also knowing that we may not fully understand the work when it’s complete; we just have to trust in each other and trust in our basic creative skills to lead us somewhere interesting.

Your last album is from 2016. Do you feel changed as a band after these two years?

Yeah, I feel like we had a lot of good experiences making the previous record and also touring on it and going to Japan together and making the record with Keiji Haino. I’ve known Brian for a long time and we were always friends but I think being in this band together has made us have a closer connection. And Nick is someone I didn’t know at all before we started playing together in Sumac and it’s been a really good process creatively and personally to get to know him. So I feel like we’re better friends, we have a greater understanding of who we are as people and we also have a deeper creative connection at this point, which gives us more freedom to try things and to embrace the adventure of collectively diving into the unknown.

How do you respond when people ask, “How would you describe Sumac?”

I would just say that it’s…

Loud?

Yeah. That wouldn’t be my first descriptor, although it’s a factor. I guess it depends on what context it’s in, but I would say that it’s experimental metal. That’s kind of the best descriptor that I can come up with for it, if pressed to give something that sort of summarizes it in a very basic way.

And how important is experimentation in music for you?

I think it’s the only way that music can evolve, and it’s the way that all important developments in music have happened. For me, just as a music listener, most of the time I find myself gravitating towards the things that feel a little bit precarious in some way, as if the people who were doing it were really going way out on the edge of their abilities and way out on the territory of what’s already known. To me that’s more engaging than hearing something that sounds like it’s really well executed and professionally performed. I think a willingness to push yourself and to scare yourself and to maybe even scare or unsettle the people who are going to hear your music is what makes it exciting and also offers the possibility for a different future. In a way, it’s kind of like you’re opening a door to what’s going to come after, rather than just looking behind you where you already know pretty much everything about where you came from and how you got there.

Faith Coloccia

And you mentioned Keiji Haino, earlier. Do you think he has contributed to Sumac’s music in some way?

I think working with him and just having that experience was really good for us, partially because it was a trial by fire. We didn’t have any time to prepare for it really. I mean, we knew it was coming but it’s not like you can write anything in advance for an improvised music session, of course. There wasn’t really any way in which we could prepare ourselves for it; we just had to go in and find out what happened. His approach was very easygoing in a way that I found really refreshing. He’s serious about what he does but he also, from my perspective, seems to approach it with a light and passionate step. He doesn’t seem to try to control any aspect of what’s going on beyond a few basic parameters about how he wants people to sound and who he chooses to play with. But other than that, it’s all about letting the moment happen as it’s happening, creating circumstances where you can have an open musical exchange with the people you’re playing with and dismantle that part of the rational brain that wants to organize and control the environment and really embrace something that seems more deeply spiritual and maybe, at some level, even more primal. I suspected all of that from listening to his music and those are also all things that I’m interested in on our own path. At the same time, I think having that experience with him and witnessing it first hand and being able to listen to what happened when we all got together was a very good step towards making Love in Shadow.I had written all of the record before we went in and recorded with him, yet even though it was all pretty much mapped out, it was somewhat altered by that experience if only in sort of freeing up our own mindset about how we approach our work and giving us a more open stance from which to work from.

You recorded Love in Shadowin a single room at Robert Lang Studio in Washington with Kurt Ballou. How was it?

Good. The studio was supposedly haunted.

Really?

Yeah, that was an interesting thing to consider when going in. I think in some way we’re interested in interdimensional experience and that’s part of where our music comes from. So to feel like we might be in a place that had that energy in it was interesting. I can’t say that we experienced anything super out of the ordinary except for lights flickering on and off at interesting times. But other than that I can’t say that it was totally different from my other studio experiences. You go in, you set up your gear, you get the sounds you want and then you just start going. To go back to what I was saying earlier, the thing that sticks out to me the most is how little time we spent really assessing what the music was. We just had to focus on making it and trusting that we were going in the right direction and that we were making something worthwhile. And our lack of familiarity with the place and with the music that we were making kind of heightened the tension of the experience, which I think was a good thing. I don’t like feeling overly comfortable when I’m making something. That always sort of connotes laziness to me. But at the same time, I’d say it was even a little bit more dangerous feeling than a lot the other records we’ve made.

Why did you decide to work with Kurt Ballou?

All of us have recorded with him in the past and we all just really appreciate the way he works and how he makes records sound. I think he’s able to capture a lot of energy in heavy music that it seems like a lot of other producers don’t have the same ear for. I think Kurt is kind of able to capture the live feeling of a band without sacrificing sound quality. He’s achieved a very good balance there where you can hear everything that’s going on and pick up on all the subtle nuances. His recordings rarely feel overproduced to me and, with Sumac, so much of our music and the intent behind it has to do with living in the moment and the physicality of sound that Kurt is basically the perfect person to help translate that.

Were there any types of sounds that you wanted to explore with this record?

Initially I wanted a record that sounded dryer and closer and more claustrophobic than the last record. The last record had such a big, roomy sound to it because we recorded in a huge room and I liked that. I wanted something that felt a little more oppressive in a way. That actually didn’t end up happening, and I think it was partially just because we recorded in another big room, not as big as the last one, but there was a lot of that big-room sound happening. Nick really likes his drums to have a lot of that very live, open sound to it. And trying to do that and make everything else sound very close and claustrophobic wasn’t a good mesh. I think we had the intent to try to do something that sounded a bit different than the last record but, sonically speaking, ended up being fairly similar. To me that’s not that much of a problem, mostly because the music itself was quite different than what we had written previously. For me that’s a little bit more important than the sonic properties of the recordings.

In what way is Love in Shadow different from your last work?

It involves more improvised passages, for one thing. I’d say that’s probably the biggest difference. That’s always been a component of our music but we intentionally expanded that this time around and left bigger pieces of each song open to interpretation. We’ve also been interested in long-form songwriting and this record is obviously even more sprawling than the last one in terms of track lengths. To me, that offers up a lot of interesting possibilities, partially because it’s easier to occupy a more focused mental state when the songs aren’t broken up into short pieces. When it’s just this long continuous thing I think it does more to break the rational mind and allow you to tap into something that’s a bit deeper and less focused on the mundane aspects of making music. It offers the possibility for a more transcendental experience.

And lyrically speaking?

I feel like I’ve dug deeper than I have before. I always try to be as honest as I can in my approach to making lyrics. I try to find a good balance between choosing interesting words and having a poetic approach and also trying to write something that feels really truthful and real to me. In a way, I dug even a little deeper in this lyric writing process than I meant to and it became a somewhat disturbing experience for me in the end. Ultimately I think it’s good but it opened up some things for me that have had lasting repercussions. Even now, more than a year after the fact, I’m still thinking about it and trying to understand everything that has come out of that process of lyric writing for me.

What are your future plans at the moment?

We have a tour that we’re leaving for this week so that’s the most immediate thing for us. And I know that all of us are getting mentally prepared for that. In fact, as soon as I get off the phone with you I’m going straight to practice with Brian. So that’s the very near future. And then we have a few more tours we’re planning in support of this record. We’re going to do more of the US in January and then we’re working on a European tour for March of next year. But we also have more recordings in the works, some stuff that we’ve already recorded and we just need to finish. I feel like there’s a lot of momentum creatively for this band and I just want to keep going with that and find out where it’s going to lead us.