In part one of this series, we saw how the French Revolution not only toppled the monarchy, but greatly diminished the power of the Catholic Church in France as well. We also examined how Satan became the conquering hero of artists and writers following the revolution, as a figure spreading enlightenment and liberty throughout France. In part two, we examined the influence of French occultist Eliphas Levi and discussed how his work laid the framework and foundation for both white and black magicians who followed in his wake, a framework capped by the enduring legacy of his image of Baphomet. In part three, we saw how easily some of Levi’s disciples slipped into Satanism and black magic, or at least lent themselves to accusations of both. Finally, we will see how all of these aspects came to a head in the Taxil Hoax.

The Taxil Hoax was the greatest hoax perpetuated in French history; a twelve year long event that took advantage of the religious and political tensions existing in post-revolutionary France while exploiting the French Satanic zeitgeist of the 19th Century to dubious ends. In many ways, it was the culmination and climax of 19th Century French Satanism, but it’s legacy still lingers today in the minds of many modern conspiracy theorists and witch hunters looking for evidence of a grand Satanic plot at every level of society. Accusations ranging from ritual abuse in nursery schools to the belief that the “Illuminati” populate the halls of national and international power all owe at least some debt to the Taxil Hoax of 19th Century France.

The roots of the Taxil Hoax can be traced to the Syllabus of Errors, an incredibly reactionary document published by Pope Pius IX in 1864 in an attempt to stem further erosion of the Church’s authority in an increasingly secular society. It essentially renounced any and all liberalisms that came out of the Enlightenment as “satanic.” As a result of its full frontal attack on the society that had thrown off the yoke of the Church in the years prior, France sought to ban circulation of the encyclical, as well as stop priests from discussing it with laypersons. In 1878, Pius IX’s reign ended and in 1878 Leo XIII was named Pope. In 1884 Leo XIII issued his own encyclical entitled Humanum genus that was no less inflammatory than his predecessor’s work. In it he divided humanity into those who serve the “kingdom of God” and those who serve the “kingdom of Satan.” Furthermore, he argued, “the partisans of evil seem to be combining together, and to be struggling with united vehemence, led on or assisted by that strongly organized and widespread association called the Freemasons.”

Imputing evil deeds to the Freemasons was nothing necessarily new, given that as the world’s leading secret society it had been subject already to many conspiracy theories, but the motivation for the Church’s antipathy toward it at this time was part and parcel of their attack on a secularized post-revolutionary France. Because Freemasonry espoused the principles of individual liberty, a free will based in reason and separation of Church and State, it was seen as a hotbed of the liberal “satanic” ideals that Pope Pius IX had attacked in his encyclical.

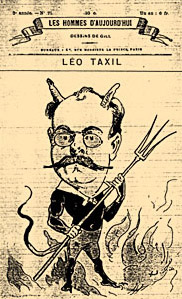

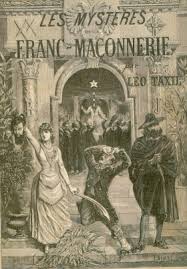

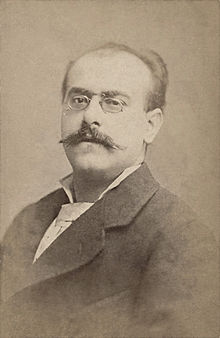

Enter Marie Joseph Gabriel Antoine Jogand-Pagès, better known as Léo Taxil. Taxil was a journalist who despised religion, particularly Catholicism. He had written satires mocking the Church and Christianity in general, and in 1881 attacked Pius IX with the semi-pornographic book The Secret Loves of Pius IX. For that work he was accused of libel. That same year he joined a Masonic lodge in Paris. He remained with the lodge for only a year, before leaving the Freemasons. Purely for amusement’s sake, according to Taxil, he hatched a plan to undermine both the Church and the Freemasons, and in the years that followed his plot began to unfold.

Enter Marie Joseph Gabriel Antoine Jogand-Pagès, better known as Léo Taxil. Taxil was a journalist who despised religion, particularly Catholicism. He had written satires mocking the Church and Christianity in general, and in 1881 attacked Pius IX with the semi-pornographic book The Secret Loves of Pius IX. For that work he was accused of libel. That same year he joined a Masonic lodge in Paris. He remained with the lodge for only a year, before leaving the Freemasons. Purely for amusement’s sake, according to Taxil, he hatched a plan to undermine both the Church and the Freemasons, and in the years that followed his plot began to unfold.

Following the publication of Leo XIII’s anti-masonic encyclical, Taxil made a very public showing of his (fraudulent) conversion to Catholicism in which he renounced his prior works and apologized for the harm caused the Church. The Church received him proudly with open arms, believing they had won over one of their most vocal and virulent foes.

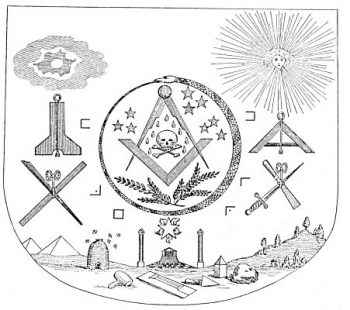

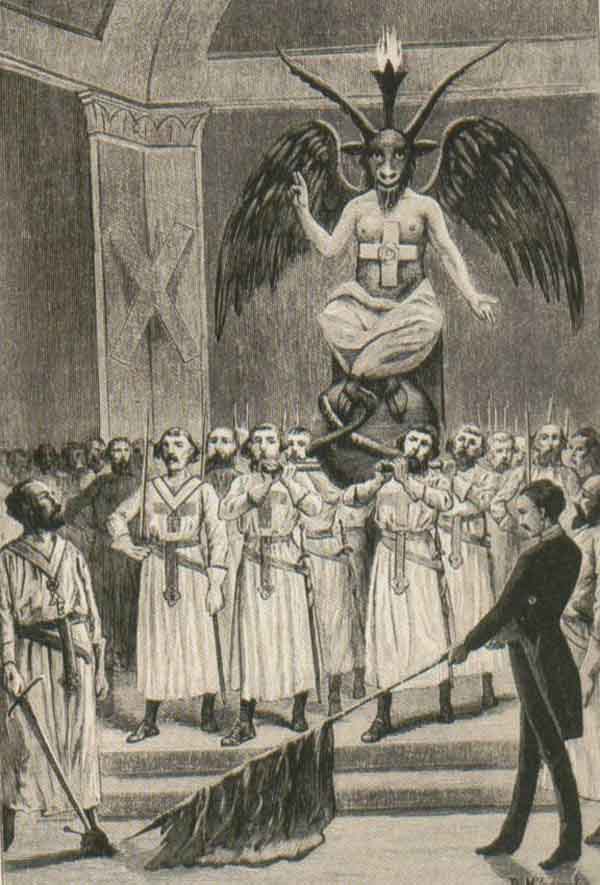

In the years that followed, Taxil produced a four-part history of Freemasonry that included fake eyewitness testimony of Masonic ceremonies performed for the glorification of their true lord and master Satan. Often these rites were sexual in nature. Following these works, Taxil produced a work titled Devil in the Nineteenth Century that introduced to the world a woman who came to be known as Diana Vaughan. Vaughan was purported to be a descendant of a union between English Rosicrucian Thomas Vaughan and the goddess Astarte. She was also allegedly a Satanic priestess who presided over the secret Masonic order know as the Palladium; the innermost secret Satanic society that controlled the Freemasons, whose end goal, of course, was world domination.

In the years that followed, Taxil produced a four-part history of Freemasonry that included fake eyewitness testimony of Masonic ceremonies performed for the glorification of their true lord and master Satan. Often these rites were sexual in nature. Following these works, Taxil produced a work titled Devil in the Nineteenth Century that introduced to the world a woman who came to be known as Diana Vaughan. Vaughan was purported to be a descendant of a union between English Rosicrucian Thomas Vaughan and the goddess Astarte. She was also allegedly a Satanic priestess who presided over the secret Masonic order know as the Palladium; the innermost secret Satanic society that controlled the Freemasons, whose end goal, of course, was world domination.

The books were accepted as fact and sold surprisingly well, particularly to Catholics who where hungry for what they saw as proof of the great Satanic/Masonic conspiracy. Taxil was taken aback by it all though, saying, “the crimes I laid at [the Freemasons] door were so grotesque, so impossible, so widely exaggerated, I thought everybody would see the joke and give me credit for originating a new line of humor. But my readers wouldn’t have it so; they accepted my fables as gospel truth, and the more I lied for the purpose of showing that I lied, the more convinced became they that I was a paragon of veracity.” In fact, Taxil was so well received by the Church that in 1887 he received an audience with the Pope, who saw him as a shining light of holiness and truth.

Playing upon his new found position as de facto mouthpiece for the Church’s anti-masonic campaign, Taxil decided to manipulate his newfound benefactors a bit more when he claimed Vaughan had broken free from the Palladians and was in hiding. He asked Catholics to pray for her soul so that she might free herself from the shackles of Satan and convert to the one true religion of the Church. His audience happily obliged by praying and performing masses for Vaughan. In time, Taxil rewarded his audience with the good news that Vaughan had indeed converted, and even produced devotional literature attributed to Vaughan praising the Pope.

All this while, Taxil continued to publish anticlerical and anti-Catholic material under other personas, as well as works purported to have been produced by Satanic Palladians, for the purpose of providing “proof” that such an organization existed in the furtherance of his grand hoax.

Having fabricated his conspiracy out of whole cloth at this point, Taxil began to incorporate elements from France’s Satanic zeitgeist to add veracity to his wild tales. He referenced Levi’s Baphomet in both word and image, and attributed strains of gnosticism and Luciferianism to Albert Pike, who was the Freemasons’ Grand Commander of the Scottish Rite’s Southern Jurisdiction at the time. In a famous quote written by Taxil, but attributed to Pike, the Grand Commander is to have said that Lucifer was the true God of light in opposition to the dark god Adonai, and that the, “Masonic Religion should be…maintained in the purity of the Luciferian Doctrine.” By couching his hoax in legitimate Luciferian teachings and iconography, Taxil added a layer of plausibility to the story that convinced not only zealous anti-Masonic Catholics of its veracity, but also members of the French public in general. Consequently, it is these elements of the story that have allowed modern conspiracy theorists to maintain and perpetuate the belief that Taxil was telling the truth all along.

Not everyone was convinced by Taxil, though. In 1896 the famous occultist A.E. Waite published Devil Worship in France, a book that exposed Taxil’s tale for the fraud it was and questioned not only the truth of Vaughan’s role as a Satanic high priestess, but of her mere existence. At the same time Masonic researcher Joseph Gabriel Findel debunked the connection between Masonic teachings and Luciferianism, and wrote that the whole farce was a Jesuit conspiracy to smear the Freemasons.

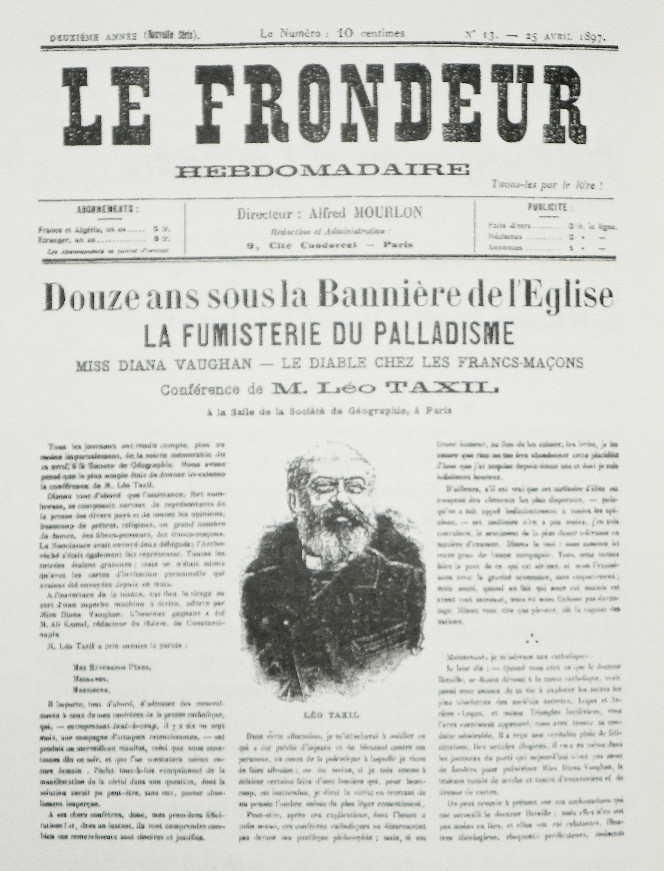

In response Taxil called a press conference with the pretense that he would physically produce the actual Diane Vaughan. On April 17th, 1897, twelve years after it began, Taxil stood in front of a Parisian assembly and admitted it had all been a hoax. The crowd reacted so angrily that he had to duck out the back of the hall to avoid violence.

In the end, Taxil said that he wanted to debase both the Church and the Freemasons. It has been proposed that Taxil was an anarchist and that his hoax allowed him to undermine two different power structures at opposite ends of the spectrum. Whether or not this is true, it is clear that Taxil found great pleasure in his charade; he is quoted as saying “I thought I would kill myself laughing at some of the things proposed, but everything went; there is no limit to human stupidity.”

Taxil’s words concerning human stupidity proved to be prophetic, as his hoax has been reproduced and used since by anti-Masonic conspiracy theorists who see Taxil’s story as proof of an “Illuminati” and a Luciferian conspiracy to control the world (It should be noted that on it’s face this conspiracy has always been absurdly contradictory given that Luciferianism is concerned with individual liberation and gnosis, not mass control by a secret cabal). An even darker legacy of the Taxil hoax is its use as source material in the Satanic Panic of the 1980s and early 90s. It has been cited as true by evangelist extraordinaire Jack T. Chick in his infamous “Chick tracts,” as well as books on satanic ritual abuse.

Unfortunately, like many of the elements of 19th Century French Satanism, Taxil’s hoax continues to influence our understanding of Satanism and the occult in general, making it difficult at times to discern fact from fiction and truths from falsehoods. Certainly, the Romantics tapped into a valid understanding of Satan as liberator, yet occultists like Levi and his disciples seemed to both promote and denigrate exaltation of the Dark Lord. In the end, upon final review of the French Satanic zeitgeist, what we are left with is a rather mixed legacy, full of promise and false starts, but one that laid the groundwork, for better and worse, for both practitioners of the Left Hand Path as well as their accusers in the century to follow.