Originally presented during the “Approaching Posthumanism and the Posthuman” conference at the University of Geneva, Switzerland, as well as the Zom(bie) Con at Drexel University, and Mikita Brottman’s “Zooontologies” course at the Maryland Institute College of Art, 2015.

Animals, a Dirge

While the Southeastern United States suffers the end of civilization in The Walking Dead[1], I can’t help but wonder where are the animals? Where are the packs of feral dogs and cats? Where are our companions? Surprisingly, in our time of crisis we travel without them. By season five we are left to wonder if what revives our dead has also killed our companions — or perhaps we’ve eaten them.

Horse

The first and most powerful representation of animal occurs during the series premiere when Sheriff’s Deputy Rick Grimes, after waking from a coma and having several run-ins with zombies drives to Atlanta, hoping to find humans quarantined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[2] Soon he runs low on gas, so he stops at a small rural home on the outskirts of the city. There he finds only death, and spirals into despair. But, this darkness fades when he hears the familiar bray of the family’s horse, and asks her[3] to allow him to mount and ride her into the city.

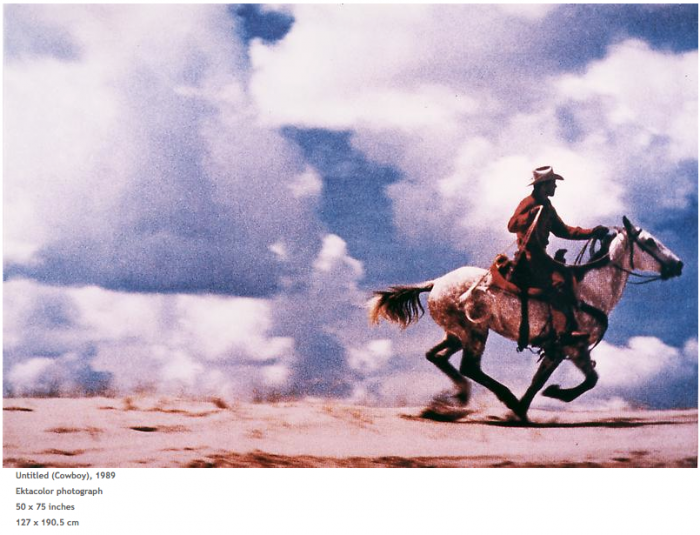

The horse gallops towards the foreboding urban landscape, but this scene—a sheriff on horseback against the Atlanta skyline—is some strange fiction, a Richard Prince Marlboro Man imbued with archetypal heroism and existential absurdity. While in the city, frenzied by a passing helicopter, Grimes compels the horse to rush in its direction. They turn a corner and encounter a horde of zombies. Surrounded, Grimes escapes off the back of the horse. As pop music plays, she is torn apart, and her entrails are consumed. She is broken one last time in sacrifice to Grimes. In one of the earliest and most violent deaths of the series, the horse is rendered ineluctably real and other, its non-human innards exposed in shocking gore.

What end did this horse’s death serve? Until very recently, no horse has been seen again, though characters have traversed hundreds of miles of rural land. And no other animal will have such an impact until an incident many years later when the starving group must consume wild dog–a faux pas in America. Consuming man’s best friend must have felt like cannibalism to some; for others it was perhaps another example of unconditional love from our former companion animal.

Postanimal, Posthuman, Postzombie in the Network

This angst, loneliness, and promised rebirth of humanity are the concerns of The Walking Dead: how are we not like the dead? Or, how are we not to become like animals: primitive, brutish, violent, and embodied? Even zombies are treated with more moral ambiguity than the animals. In contemporary popular zombie-media, redemption comes at the expense of other living species. In the representation of the animal and consumption, the visual rhetoric furthers various strands of posthumanism.

By posthuman I mean the narrative of the end of the anthropocene as portrayed in the zombie-apocalypse–thus literally the end of human dominance. But this cinematic tradition has regained popularity as a reaction to our networked condition. Therefore I refer also to the philosophical tradition that describes humans as transformed by technology.[4] As a disruption of humanism, posthumanism is concerned with cybernetic advances and hybridity. For N. Katherine Hayles, the dream is of a posthuman who “embraces the possibilities of information technologies without being seduced by fantasies of unlimited power and disembodied immortality, that recognizes and celebrates finitude as a condition of human being, and that understands human life is embedded in a material world of great complexity, one on which we depend for our continued survival.”[5]

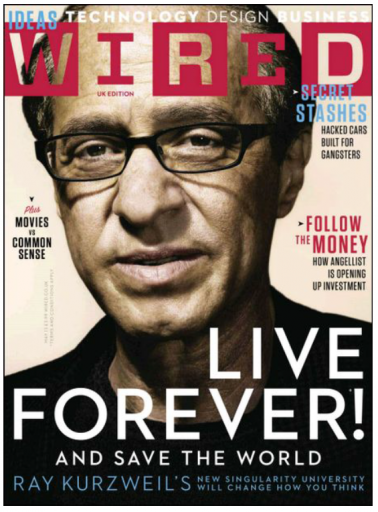

But for all its progressive elements, posthumanism repeats the mistakes of Cartesian dualism—disembodiment by the primacy of cognition. In an increasingly networked culture, Hayles’ dream is deferred by the all-consuming rhetoric of transhumanism. Futurist Ray Kurzweil’s goal is not only immortality, but also the ability to raise the dead by digitizing artifacts of lives (particularly his father’s) and importing them into avatars.[6] Our network devices are our appendages; we are already cyborg, but the transhumanist seeks transcendence in the singularity. It is a search for human perfection, or apotheosis despite our bodies. Our network environment has further eroded our human-to-human otherness, reducing our difference to standardized interfaces and common codebases. Time and space are compressed. Forget globalism, the new rhetoric of the transhumanist is the glocal society: peace, love, and apps. With this globalism of the local comes the end of the stranger, not really in-real-life (IRL), but in rhetoric. If in a network condition, we are all friends, then where have the others gone?

As a number on a friend’s list, the user is transhuman in a viral network, and also a zombie, or the living-dead. This is not Hayles’ posthuman, but a different being spreading the dead ideas of universal human nature and scientism. The mind-body problem is now also the ghost-in-the-machine, literally. As the death of users increases, who will delete the accounts of the dead? Who burns the bodies to stop its spread? The meme of the zombie apocalypse is a result of these network identities, compressed into Paul Virilio’s transhorizon global time of false days, and world time of tele-surveillance media. [7] This is our glocal hometown of everybody –all is similar, everyone in the know, and all publically consumed. Forget fears of NSA surveillance –the culture of surveillance is now an embedded expectation, a conditioning under the guise of equality, and the rhetoric of the great hive mind espoused by singularitarians. How can we not feel like the living-dead in these social spaces –here and not here, alive and dead, on and offline?

The online ghost of former Beatle, George Harrison, congratulates his bandmate, Ringo Starr, screenshot by the author.

Our glocal unification intensifies the otherness of the only stranger we have left, the animal. Our last act of humanism is speciesism, under the guise of the transhuman, which is in a sense hyper-humanism: if our technology defines us, we become more ourselves the more we transcend ourselves. From the 1960s to the present, shock and horror films have visually defined and critiqued otherness against the backdrop of a rapidly shifting sense of geography due to broadcast extensions of man. Current media repeat earlier tropes, but today they fulfill the rhetoric of the glocal society, breaking down geographic borders and finding otherness in the animal in order to defend the world spirit of the human network while simultaneously returning to flesh.

Old World & New World Zombiism

The zombie of The Walking Dead is informed by George A. Romero’s original trilogy.[8] But, unlike The Night of the Living Dead’s critique of American hubris in Vietnam and civil unrest at home, The Walking Dead ignores even slight socio-political critiques, only touching on issues of power. Instead, it is a tale of the ancient tragedy of fallen man. Since the rhetoric of transhumanism applies universal human nature, then there is no room for politics. Moving beyond Romero’s satellite and radio broadcast culture, The Walking Dead is filmed during an era of full immersion in the network of the expansionist Internet and its culture of personal celebrity. The zombie’s return, then, relates in part to the Internet adaptation of Richard Dawkins’ evolutionary cultural phenomenon, the meme and its extension to “friendship.” We are part of the network and we are the network. We are all potentially viral, and in our confusion we seek others by consuming virtual bodies. Most contemporary zombie storylines revolve around a similar struggle of the one versus the many. We are alone together.

Survivors gather around a television screen, watching broadcast news media of the 1960s during the Night of the Living Dead, screenshot by the author.

While Romero’s original film hinted at otherness, few others of the American genre do. Instead, as Ian Olney points out, it is European zombie and cannibal films of the 1970s and 1980s that explicitly critique European colonialism. References to voodoo, black magic, or, Western science’s inability to cope or explain how the dead rise, serve as critiques of greater colonial and globalist agendas through the othering of the non-westerner often by camera lens. Olney explains that these zombie films deconstruct “the historical relationship between colonizer and colonized in an effort to interrogate the racist and imperialist attitudes informing it. In these movies, the figure of the zombie emerges not as a symbol of postmodern angst, but as an agent of postcolonial rage –a monster whose virulent contagiousness threatens the destruction of the imperialist Western culture that produced it.”[9]

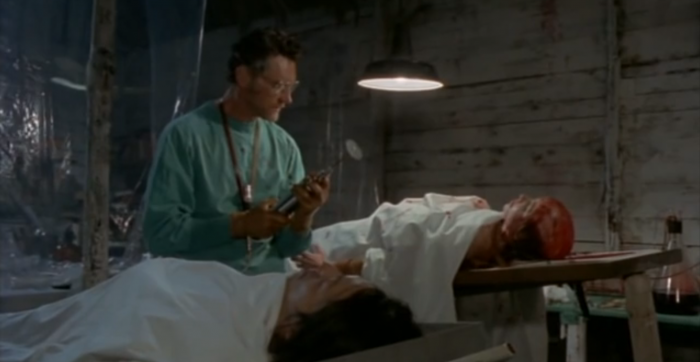

A mad scientist performs a brain transplant from the living to the dead, in Zombie Holocaust, screenshot by the author.

Lucio Fulci’s Zombie (1979) and Marino Girolami’s Zombie Holocaust (1980) both take place in a former domain of Western imperialism, and, in both bumbling characters of white European descent become involved in the mistakes or misguided attempts of a central European scientific figure to explain zombiism. For Zombie Holocaust, a megalomaniacal scientist creates his own zombie slave horde through brain transplants in an effort to extend man’s life–achingly familiar to Kurzweil’s own theories of zombie-avatars. Yet, in regards to animal representation, only the infamous zombie versus shark battle in Zombie remains both memorable and awkwardly unnecessary.

Mondo Boom & Consumption

In order to better understand the murder of the horse in The Walking Dead, we must connect this strategy of the exploitation of otherness to globalist representations of the past. In 1962’s award winning Mondo Cane[10] we are presented with a self-proclaimed work of documentary, or travelogue, even where scenes are manufactured. Grandiose in scale, with dramatic framing and featuring a powerful score by Riz Ortolani, the film portrays, often in racially insensitive terms, other cultural practices around the world from Italy, Taiwan, to Tokyo and the U.S.A. to name a few. What binds the film’s lack of any coherent narrative is an underlying interest in the use and consumption of the non-human animal. What is most memorable to the viewer are the scenes of a restaurant serving skinned dog, the skinning alive and paper bagging of snakes, the force feeding of geese, the severing of a bull’s head with one strike of a sword, among other practices. In the case of the dog eatery, the scene that follows is a sarcastic portrayal of a Western pet cemetery, with wealthy bereaved mourning their companions, while other dogs urinate on gravestones. Mondo Cane’s pseudo-documentarianism attempts to confuse and re-create the real by portraying a violent global village, bound by blood and sacrifice; we are all the same in our strangeness. So successful was the exploitative strategy of Mondo Cane, that a genre of similar films resulted using mondo in their title, along with others like Faces of Death, taking documentary to its extreme by presenting footage of human death scenes.

Informed by mondo, the later European cannibal boom genre is known for extended, explicit death scenes featuring genital mutilation, impalement, rape, and the abuse and murder of animals –this time not as documentary but in service of a work of metafiction. Most famously, Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust (1980) centers on an American anthropology professor’s search for a documentary crew who have gone missing in the Amazon. What Dr. Monroe finds is that the filmmakers have been killed and

The infamous impalement scene from Cannibal Holocaust had to be proven “fake” in court, screenshot by the author.

consumed by a local tribe as an act of revenge. The film canisters of the deceased filmmakers reveal that the crew were murderous rapists, who set fire to villages, and encouraged violence in order to sensationalize their documentation (perhaps a critique of the mondo filmmakers). Using the hand held, shaky camera style, Cannibal Holocaust violently ruptures the passive position of the viewer by forcing us into the role of witness through its extreme gore, and therefore explores what Mikita Brottman calls cinéma vomitif: “nausea, repulsion, weakness, faintness, and a loosening of bowel or bladder control –normally by way of graphic scenes featuring the by-products of bodily detritus: vomit, excrement, viscera, brain tissue, and so on.”[11]

The most vicious scenes are left for the animal: the stabbing of a muskrat, the shooting of a small pig, and the severing of a monkey’s skull. Most brutal, is the tearing apart of a living river turtle, long and drawn out like a giallo death scene, the documentary crew severe the turtle’s head and violently rip apart its shell. They later cook and feast upon its flesh. At the conclusion of the film, while standing amongst the skyscrapers of New York City, Dr. Monroe solemnly asks, “I wonder who the real cannibals are?” Deodato, while surely creating a work critical of media sensationalism, still uses the animal in service of the real in his simulated search for human otherness. After a scene of real animal mutilation, we are presented with a simulated one of human disembowelment which is made all the more real by its context. The animal is a tool, a visual trick, for a brutal Kuleshov Effect, thus contradicting Deodato’s critique of Western visual culture and the pornography of violence. Today, the film continues to confuse viewers as to its authenticity, as its tagline reads: “The One That Goes All The Way,” but for the non-human, it is a snuff film.

The violent film crew capturing a river turtle, who is killed on camera in Cannibal Holocaust, screenshot by the author.

OMEGA MAN: a travelogue

During the rise of the first wave of mondo, zombie, and cannibal cinema the globe was a mystery, filled with strangers. Mondo filmmakers documented this otherness, sensationalized it and shocked us. The Euro-zombie and cannibal film warned us of the colonial aspects of representation, especially through new broadcast and network media of which we are conditioned for today. Cannibal Holocaust pulled the rug out from under the project. The real and its representation are in tension; the audience is thrust into performative spectatorship, through its self-reflexivity and violence. We are witnesses to a crime, to atrocities; so how should we act?

The Euro-man returns to the primitive and forces the other into a state of nature; exploring and colonizing with camera lens. But, it is the disappearance of all this, as in, the loss of strangers, of otherness, which is anticipated. The end of the rainforest; the end of man. What are we left with today, when only a single individual of an Amazonian tribe survives and is geo-mapped and surveilled by Brazilian authorities who, in a Policy of No Contact, cordons off land to let the man die in a state-of-nature, his own zoo?[12] The human other is nearing extinction. If it is then the end of human-difference, then the zombie, uncomfortable with its doomed status, seeks difference again in an attempt at curing the virus. Virilio writes:

The Earth, that phantom limb, no longer extends as far as the eye can see; it presents all aspects of itself for inspection in the strange little window. The sudden multiplication of ‘points of view’ merely heralds the latest globalization: the globalization of the gaze, of the single eye of the cyclops who governs the cave, that ‘black box’ which increasingly poorly conceals the great culminating moment of history, a history fallen victim to the syndrome of total accomplishment.[13]

Uncontacted Indians in Brazil in May, 2008 defending themselves from the camera, image acquired at http://www.uncontactedtribes.org

As geography disappears to virtuality, we seek brotherhood in our glocal village while simultaneously disembodying and distancing ourselves from nature. This tension is expressed through the adventures of television personality and chef, Anthony Bourdain. Something of a rock star, Bourdain is now a network brand. In his program Parts Unknown[14] the chef travels across the globe, focusing less on the specifics of culinary arts and cuisine, and more on culture and dialog. From the USA to the Congo in crisis, Bourdain seemingly places himself and his film crew in danger, fearless and rugged, an American frontiersman.

The “unknown” is what fascinates Bourdain and his audience as we are reminded that real-distance can exist in the virtual; and perhaps still so might mystery and strangers. In our quest for geography and otherness, we simultaneously spread our sameness. So we share our similar interest: imbibing, smoking, and consuming. But, we do not simply consume; we consume flesh, together, and in this blood oath we rediscover our humanity at the expense of the animal.

Bourdain achieves this by not shying away from representing the slaughter of animals on screen, even by his own hand. All the while, American Ag-Gag laws prevent documentation of factory-farmed animals. For Bourdain, there is no greater bond for cross-cultural dialog than through this act and consumption. A vocal critic of vegetarianism and especially veganism, both in terms of cuisine and ideology, Bourdain likens the lifestyle to a “first world phenomenon” and “self-indulgent.” [15] It is difficult to separate the chef persona from that of some mega-man, proving man’s virility through the on-screen butchering, which, explains Carol J. Adams, “enacts literal disembodiment upon animals while proclaiming our intellectual and emotional separation from animals’ desire to live.”[16]

Bourdain haphazardly killing a chicken while crossing the Congo during Parts Unknown, screenshot by the author.

During an episode Bourdain fulfills a boyhood dream of boating across the Congo River. While boarding, he alerts viewers to the lack of refrigeration on the ship, therefore, chickens are brought on board. When the time comes, Bourdain and crew force the chickens into funnels where only their heads and throats are revealed. With blunt knife, they are beheaded by the crew. The chef explains to his audience that the rule of the boat is to eat you must participate in the slaughter.[17] And yet, the following morning Bourdain and his crew eat from cans of Spam –a moment left unexplained.

This scene is all too familiar as it repeats the motifs of Mondo Cane’s spectacle of global unity through broadcast slaughter and consumption. Parts Unknown re-defines otherness, but, in an age of glocal zombiism. Unlike the critique made in Cannibal Holocaust, the ideology of transhumanism accepts our extension as progress. However, there is a terror that ensues by the denial of our own body and ego –in the end we seek difference. If uniqueness and individuality are gone in the posthuman, then, the transhuman may at least champion the species above all else. With the death of strangers, only the non-human is left to sacrifice and remind us of our unique power, our hierarchy, our glory and perhaps, save us from our fear of loneliness, nothingness, and boredom.

So drags on the long, torturous death of humanism. In the face of the posthuman apocalypse, the transhuman rallies around speciesism, consuming old media tactics of representation, with Bourdain acting not as their mega man, but rather, omega man.

[1] AMC 2014-15.

[2] The Walking Dead premiered in 2010.

[3] My decision to use a female pronoun for the horse is important to my critique. As Carol J. Adams explains, the use of a generic “it” only participates in distancing and objectifying the animal in question. Adams writes, “But just as the generic ‘he’ erases female presence, the generic ‘it’ erases the living, breathing nature of the animals and reifies their object status.” The Sexual Politics of Meat, Bloomsbury, NY, 2010, 93.

[4] N. Katherine Hayles explains posthuman to mean not necessarily a real end of the human species, but instead, “the end of a certain conception of the human…”[4] referring to liberal humanism’s application of a universal human condition often criticized for resulting in disenfranchisement based on ethnicity, race and gender. How we became posthuman: virtual bodies in cybernetics, literature, and informatics. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1999, Page 286.

[5] Hayles, 286.

[6] “Buying Gold & Futurist Ray Kurzweil On Melding Man and Machine,” The Rundown, PBS, Interview with Paul Solman, July 10, 2012, http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/buying-gold-and-futurist-ray-kurzweil-on-melding-man-machine/ & regarding raising of the dead, http://www.pbs.org/newshour/making-sense/ray-kurzweil-on-bringing-back/

[7] The Information Bomb, Paul Virilio, Verso, NY, 2005, “After the ‘end of history’, prematurely announced a few years ago by Francis Fukuyama, what is being revealed here are the beginnings of the ‘end of the space’ of a small planet held in suspension in the electronic either of our modern means of telecommunication.” page 7, and, “There lies the great globalitarian transformation, the transformation which extraverts localness –all localness –and which does not now deport persons, or entire populations, as in the past, but deports their living space, the place where they subsist economically. A global de-localization, which affects the very nature not merely of ‘national’, but of ‘social’ identity…” page 10, and, “…substitute horizon: the ‘artificial horizon’ of a screen or a monitor, capable of permanently displaying the new preponderance of the media perspective over the immediate perspective of space,” page 14.

[8] Night of the Living Dead (1968), Dawn of the Dead (1978), Day of the Dead (1985)

[9] Euro Horror: Classic European Horror Cinema in Contemporary American Culture, Ian Olney, Indiana University Press, 2013, page 207.

[10] Mondo Cane is written and directed by Paolo Cavara, Franco Prosperi and Gualtiero Jacopetti

[11] Offensive Films: Toward an Anthropology of Cinéma Vomitif, Mikita Brottman, Greenwood Press, Connecticut, 1997, page 11.

[12] “The Most Isolated Man on the Planet,” Slate, Monte Reel, August 20, 2010, http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/dispatches/2010/08/the_most_isolated_man_on_the_planet.html & Survival International http://www.survivalinternational.org/

[13] Virlio, 18, author’s emphasis.

[14] CNN 2013-present.

[15] “Anthony Bourdain: Vegans are ‘self-indulgent’,” Ann Oldenburg, USA TODAY, October 14, 2011, http://content.usatoday.com/communities/entertainment/post/2011/10/anthony-bourdain-on-chefs-vegans-omelets-drugs-and-more/1#.VS1X25PQNRk & “Anthony Bourdain on why he hates vegetarianism,” Disco Filter, YouTube, uploaded October 26, 2007, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i-P2g7smQME

[16] Adams, page 66.

[17] Adams, “People with power have always eaten meat,” page 48.