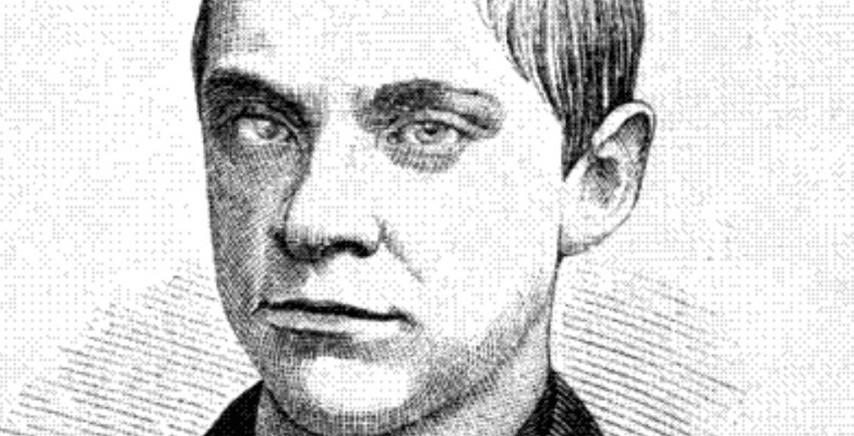

via True Crime

Jesse Harding Pomeroy has few, if any, rivals for the title of naughtiest boy in American history. Other lads have wrecked trains, burned buildings, and done away with their friends in all sorts of cruel and imaginative ways. But Jesse makes them all look like dirty-faced angels “hooking” apples from a cranky farmer.

Jesse was not an occasional miscreant. He was no Saturday night saboteur or casual killer of playmates. Jesse’s crimes were vicious, unrepentant, and ongoing. He enjoyed every minute of ’em, freely violating the laws of God and man, all the while wearing a wickedly ecstatic grin on his face. Many bad children outgrow their violent delinquency to become upstanding citizens, or at least sensible, respectable criminals. Not Jesse. He was well on his way to becoming the next John Wayne Gacy. When they finally sent him away to prison for good at the ripe old age of 14, a mere life sentence wasn’t enough. The good people of Massachusetts were so incensed with Jesse’s crimes, they made him stand in the corner all by himself for the first 40 or so years.

It’s not hard to understand what made them so mad. Jesse was a very, very naughty boy—the Jack the Ripper of the junior high school set. He specialized in torturing, and sometimes killing, young boys between the ages of 4 and 8, using an elaborate modus operandi involving ropes, knives, pins, and sticks. He killed two children and assaulted at least seven more in a criminal career that scarcely spanned a year. At times, he was attacking a boy a week. Nor was he simply acting on some adolescent peevishness or making an unconscious, pre-New Age “cry for help”. Jesse knew exactly what he was doing and why. He loved it! Although contemporary accounts make no mention of any overtly sexual acts, every one of Jesse’s attacks was marked by strong overtones of sexual sadism. His surviving victims invariably remembered Jesse smiling, even laughing as he beat and stabbed them.

All this, and it was only 1872. Grant was President, Victoria Queen. The Transcontinental Railroad had just been completed. Jules Verne was finishing Around the World in 80 Days. George Custer was riding strong, still several years from his encounter with Sitting Bull. Even Jack the Ripper was 14 years away from his ascension into myth. And there was Jesse, short pants, high collar and all, terrifying Boston with crimes lurid enough to keep a regiment of modern day true crime hacks busy churning out cheesy red-on-black paperbacks with titles like The Tot Torturer or The Boston Boy Killer.

Early warning signs

For all the horror of his crimes, Jesse had a surprisingly normal background. He was born in Charlestown, Massachusetts on November 29, 1859. His mother was a seamstress, his father a laborer in the nearby Boston Naval Yard. His father later quit this job to enter the butcher business. Years later, after Jesse’s arrest, Sunday supplement theorists found great significance in this career change. Mrs. Pomeroy, however, shot down this theory. Her husband’s duties primarily involved toting cattle carcasses around the market. Jesse had not spent his formative years helping Dad at the slaughterhouse. Jesse’s flair for butchery needed no such external inspiration.

Jesse had been a sickly baby. He developed a serious “humor” shortly after birth. He recovered from this apparently serious affliction (whatever it was) by the time he was seven months old, but it left him scrawny and frail. Either the humor or another infant illness scarred the cornea of his right eye, leaving a noticeable mark. But he rallied back from these early health problems. Save for the spot on his eye, he looked like any other chubby toddler, romping around the flat and playing with his older brother Charles by his third birthday.

However, all parties (save his mother) agree that there was something noticeably strange about Jesse from an early age. He wasn’t just another nice normal little boy. It’s not that he was especially bad. That came later, in spades. Unlike many of his brethren in the multiple murderer fraternity, his younger years weren’t a confusion of habitual truancy, strangled puppies, and playground brawls. The only dark portent from his childhood is a neighbor’s possibly apocryphal story about 5-year-old Jesse stabbing a cat and tossing it into the river.

No, the odd thing about Jesse was what he wasn’t doing. He seldom played, or even spoke with the other children in the neighborhood. Even as rambunctious games of “old cat” and “kick the can” raged up and down the street, Jesse quietly remained aloof. He preferred to spend his time reading dime novels, especially those published by the Beadle and Munro publishing houses. His favorite series was based on the grisly exploits of Simon Girty, a real-life renegade white man who led the Shawnee Indians on many a frontier settler massacre in the 1780s. His subsequent activities showed undeniable touches lifted from cowboy and Indian dime novels. But the feeling around the neighborhood went deeper than the traditional prejudice against bookish youngsters. Jesse wasn’t just anti-social; he was anti-social in a weird way. There was something about the boy that was “not quite right.”

Nor was school the environment where he flourished. He was a good, but not necessarily outstanding, student. One teacher described him as “peculiar, intractable, not bad, but difficult to understand.” When he gave an answer, it was the answer. Jesse did not take kindly to any corrections. Nor was he a shame-faced recipient of punishment. He consistently displayed great bitterness and a stinging sense of injustice towards any disciplinary measures, no manner how minor or well deserved.

It’s a time-honored tradition for relatives of any weird criminal to finger some medical mishap as the turning point that sent the family lunatic to his or her gory rendezvous with destiny. For Jesse, this wasn’t the traditional bump on the head but a serious case of pneumonia he caught in October of 1871. During his illness, he went through many crises and was frequently delirious. Even after he recovered, his mother (whose irrational support and defense of her problem child was almost pathological) recalled that he remained “not so well.”

His first victims

Jesse celebrated his 12th birthday shortly after his recovery. A few weeks after he passed this milestone, it suddenly became very unpleasant to be a little boy in the Charlestown/Chelsea area. The first attack came around Christmastime. In Chelsea, a Boston suburb across the river from the Pomeroy home, an older lad enticed a small boy up to a remote area on Powder House Hill. As soon as they were alone, he forced the younger child to take off all his clothes and tied him to a beam. He then took a rope and, brandishing it like a whip, flogged the child into unconsciousness.

In the months that followed, at least three more young boys in the Chelsea-Somerville-Charlestown area, most 7 or 8 years old, suffered similar, yet increasingly brutal and perverse assaults at the hands of the mysterious “boy fiend.” Lured to remote areas (generally Powder House Hill in Chelsea) he would force them to strip and bind them to a post or beam. He would beat them with a stick or whip them with a rope and force them to say naughty things like “kiss my ass.” Often, he cut them with a knife and shoved pins into their bodies. He paid special attention to the area around their eyes (mutilating their faces for life) as well as their genitals and thighs. Every one of the victims reported how much their brutal assailant enjoyed these torture sessions, jumping about with a smile on his face and laughter on his lips as his little victims writhed in pain.

Needless to say, the public objected loudly to these hi-jinx. The police were under considerable pressure to capture the perpetrator of these outrages. So far, the fiend’s victims had all survived, but it seemed only a matter of time before he went too far. The City of Chelsea offered a $1000 reward, and the police launched an aggressive investigation. Many a neighborhood bully found himself under suspicion. At least 17 youthful hooligans were arrested and paraded in front of the little victims. Each time, the battered little boys shook their heads. No, that wasn’t the boy torturer.

The attacks stopped as quickly as they began in late July. But by early August, another series of sadistic assaults on young boys started in South Boston. The modus operandi matched the Chelsea attacks. Victims were lured to lonely areas, generally by the shore or the train tracks, forced to strip, bound, beaten, and cut. By mid-September, at least three more boys had been assaulted.

Meanwhile, things had not been going well in the Pomeroy household. Jesse’s father packed up and left, leaving Mrs. Pomeroy the daunting prospect of providing for their two boys. But she was a resourceful woman. She rented a small storefront in South Boston at 327 Broadway and made it into a dressmaking shop. And in August of 1872, the small family moved into a flat across the street at number 312. It wasn’t easy; both boys had to help out in the shop. Charles also took a job selling papers. Oddly enough, their move coincided almost exactly with the end of the Chelsea attacks and the beginning of the South Boston outrages.

Meanwhile, the boy torturer claimed his final victim on September 17. Using his undeniable gift for gab, he enticed a boy, apparently 5-year old Robert Gould, away from his home to a lonely spot near the railroad tracks. (No one can agree on the exact order of Jesse’s victims.) He forced the terrified child to strip, tied him to a telegraph pole, cut him about the face and whipped him.

The boy torturer had assaulted his last victim—at least for now. According to Jesse’s autobiography written a few years later, Jesse was innocently strolling by the police station a few days after the Gould attack when a cop walked out, accompanied by victim Joseph Kennedy. The cop beckoned Jesse to step inside. Jesse later wrote “I told him I had done nothing, and commenced to cry. I was so frightened.”

At the station house, a few of the South Boston victims identified Jesse as the boy who’d attacked him. Jesse later begged to differ:

…those boys that had been so maltreated by another came and said that I was the boy that did it to them and the only way they identified me was because I had a spot on the right eye.

The police also suspected Jesse may have had a hand in the earlier attacks in the northern suburbs. They brought Johnny Balch down from Chelsea. Overjoyed, the small, now-scarred boy excitedly jumped about and exclaimed, “That’s the boy who cut me.”

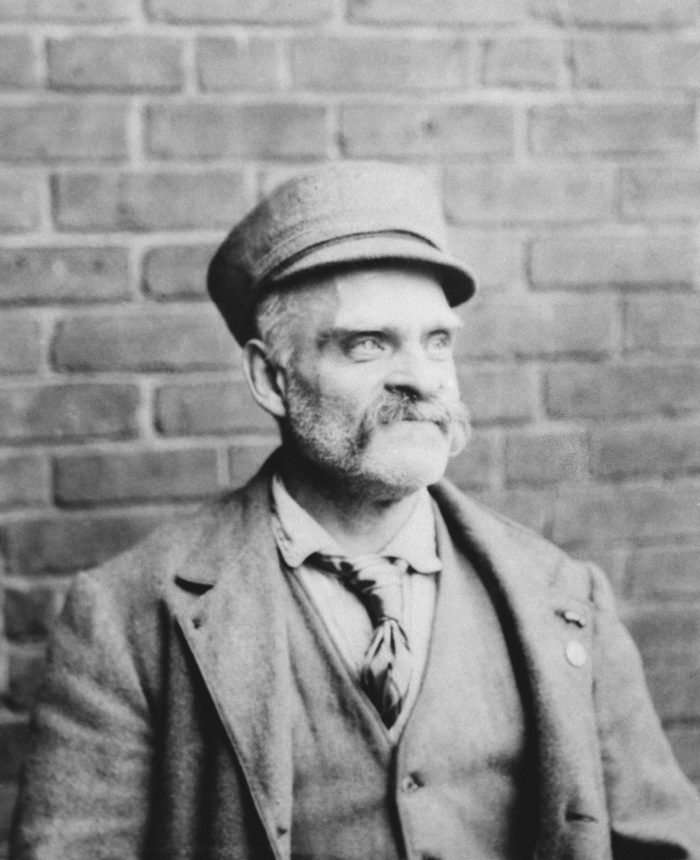

Jesse Pomeroy, was imprisoned in 1870 in Charlestown, Mass., and died there Sept. 29, 1932. He was believed to be the oldest prisoner in the U.S. (AP Photo)

John Marr is the former editor of the zine Murder Can Be Fun. Further information here and here.

This article originally appeared in Murder Can Be Fun