Photos & Text by Andrew Houston

Rapid economic growth in post-war Japan brought on a construction boom and with it a huge demand for day laborers, who came from around the country to recruitment sites such as Osaka’s Kamagasaki. As Japan grew, so did the population of these “labor towns”, which by the 1970s were inhabited almost entirely by single dwellers living in flophouses and ramshackle hotels. When Japan’s economic bubble burst in 1991, these areas were the first to feel the shock. Today, the “labor towns” of the postwar era have become “welfare towns.” Thirty percent of the population of Kamagasaki is homeless, with many more one step away as they struggle to make ends meet in the midst of economic stagnation.

The aging inhabitants of Kamagasaki face a grim reality. Many feel betrayed by a country their hard work helped build, a country that has forgotten them. Eyesores to government officials concerned with re-election, slums like Kamagasaki have been removed from maps in Japan. Officially, they don’t exist.

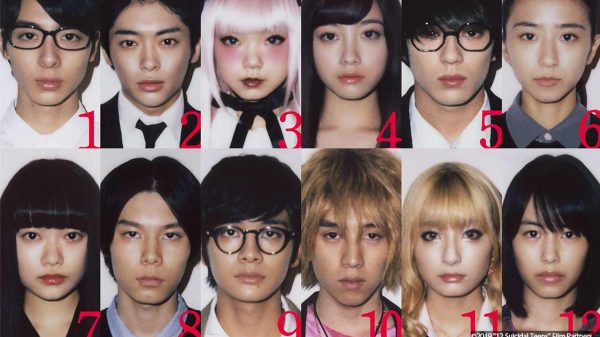

Both the construction and vice industries are controlled by the mafia in Japan, who have always had a strong presence in labor areas such as these. Though it may be easy to view the Yakuza as a predatory organization, exploiting the poor in these areas, the reality is not so simple. The line between gangster and citizen is blurred in the ghetto, where tight relationships have formed in the common interest of survival. The mafia provides the large majority of what little work there is to be had here, and many of the local mobsters themselves have fallen on hard times, and live on the street alongside the people to whom they provide work and entertainment.

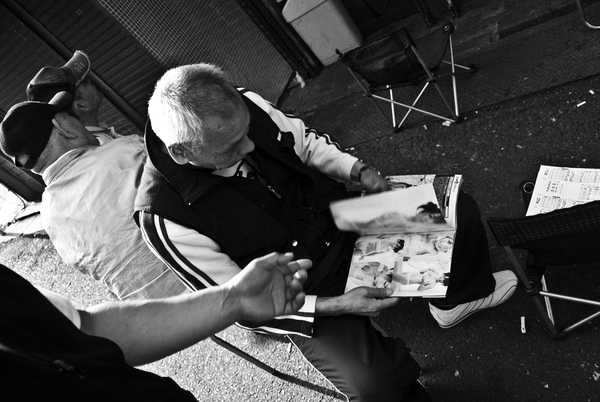

I walked the streets and met the people who live on them. Japan’s slums are inhabited by once hard-working people, and they maintain a solemn pride. Despite their grim situation, some remain cheerful, and patiently await the next job, whenever it may come. Many others have succumbed to the vices of gambling, drinking, and drug addiction.

Their story is not only that of a hard life in the ghetto. It is the story of an aging nation and a tectonic shift in cultural values. In Kamagasaki I can see a faded reflection of the excitement and hope of post-war Japan on the move. I can also see a glimpse of harsh reality on the horizon as Japan faces an approaching population crisis. To the residents of Kamagasaki, it’s just another day.