A weathered bronze statue overlooks Norwich’s Hay Hill. It depicts English writer and occultist Thomas Browne, his head resting against one hand as he contemplates a broken urn in the other. Overseeing this sullen pose are the tall, arched stained glass windows of St Peter Mancroft church. They are blackened with years. And between the two edifices is a tale of morbid irony.

Browne published Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial in 1658. It’s not what he’s most famous for but it’s more tangled into with the fabric of Browne’s life than his other books. The book’s opening page sees Browne ask, with unseemly foresight of his own after-life:

But who knows the fate of his bones, or how often he is to be buried?

Browne’s appearance as a notable figure in history was almost accidental. It came after some unknown person published an unauthorized edition of his Religio Medici in 1642, a text initially intended only for friends and family. The writer made a decision to publish it officially the following year, and it went on to become a best-seller throughout Europe.

By the time of his death in 1682, Browne made his name as a philosopher of science, religion and the esoteric. Since his death he’s also become recognized for his eccentricities. He is described by one historian as a “collector of curiosities… coiner of words… and expert witness at a witch trial”. And he remained a subject to history’s esoteric twists throughout his life. Browne died, for example, on 19 October – his birthday. In a piece of writing that has become known as Letter to a Friend, posthumously published in 1690, Browne wrote:

that the first day should make the last, that the Tail of the Snake should return into its Mouth precisely at that time, and they should wind up upon the day of their Nativity, is indeed a remarkable Coincidence

He drew these remarkable coincidences to him even beyond the grave, though. Urn Burial is a study into the burial rites and funerary customs of Western cultures through history. It treads a melancholic path along humanity’s relationship with mortality. And, in it’s third chapter, Browne writes that:

To be knav’d [gnawed] out of our graves, to have our skulls made drinking-bowls, and our bones turned into pipes, to delight and sport our enemies, are tragical abominations escaped in burning burials.

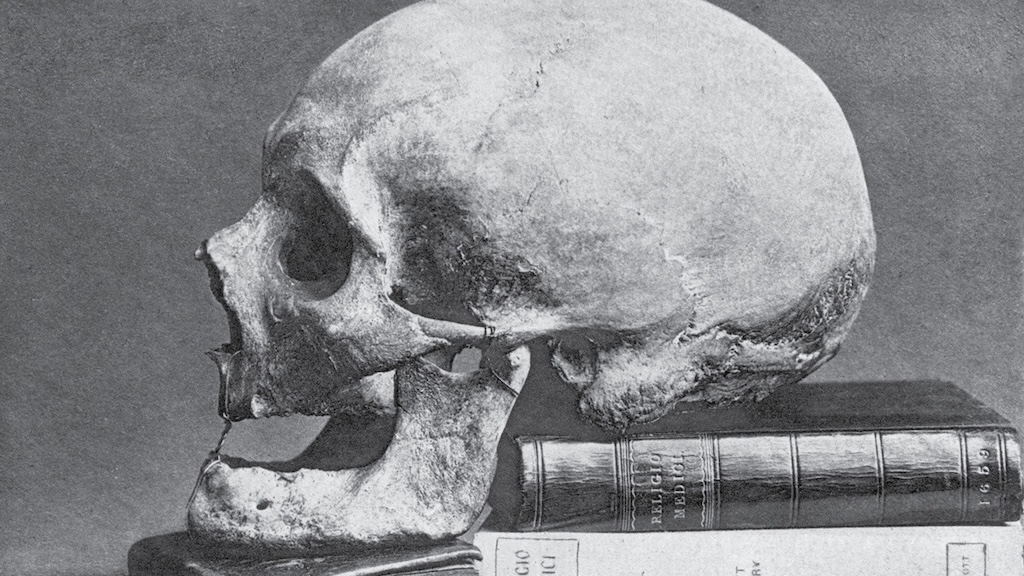

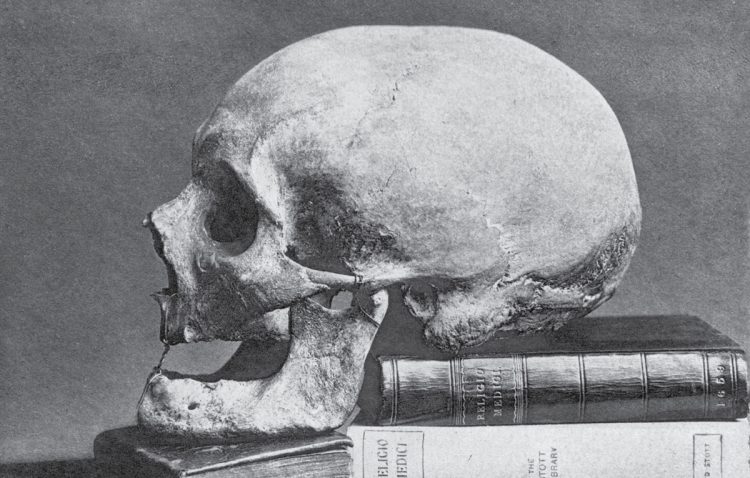

Browne’s body was buried in the chancel of St Peter Mancroft church. His coffin lay undisturbed for nearly 150 years. But workers, creating a burial vault for the wife of the church’s reverend, broke open his coffin lid in August 1840. The church’s sexton George Potter, seizing his chances, took the skull. His motive appeared to be money as he twice tried to sell it. Surgeon Edward Lubbock eventually purchased it from Potter to add to his collection of curiosities. On his death. Lubbock handed the skull over to the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital Museum.

It laid there, an icon to history’s sardonic humor, until January 1922.

After a brief journey to the Royal College of Surgeons in London – where it was photographed and casts were made – the skull was returned to the rest of Browne’s body in July of the same year, nearly a century after it had absconded the grave. When re-interred, Browne was noted in the burial register as aged 317 years. It remains there today.

The weathered bronze statue outside of St Peter Mancroft church was erected in 1905. It too has had a restless life. And today there are further sculptures to Browne scattered across Hay Hill: a piece of brain, a slice of eye, his book titles cut up and engraved into marble benches.

How many times will Browne have to be buried?