During a talk at the Building Institute in 1975, Russian film-maker and theorist, Andrey Tarkovsky, was asked of his film Mirror: ‘What is the subject of Mirror, its idea, moral, plot, development, denouement?’ Tarkovsky’s response was unabashedly postmodern: ‘The writer of that question clearly considers that all those things are essential in any work of art. In reality the concept of things that “have to be” is incompatible with art.’ For Tarkovsky, ‘A work of art, of whatever art form, is constructed only according to its own principles, and is based on its own, inner, dynamic stereotype.’

The principles that exist between Elizabeth Fraser, of Scottish alternative-pop act Cocteau Twins, and Japanese folk bluesman, Kan Mikami, are, in some ways, poles apart. On the one hand, there is the otherworldly pop of Cocteau Twins, whose shimmering, reverb-heavy guitar ambience lifted the soprano virtuosity of Fraser in dream-like swathes of hypnagogic ethereality. And on the other there is the broken blues of Kan Mikami, whose sharp and jagged guitar twangs are held close to his strained vocal laments. But somewhere in the middle, between this broken bluesman and the ‘voice of god‘, in a place just like Tarkovsky was talking about, Fraser and Mikami meet.

The principles that exist between Elizabeth Fraser, of Scottish alternative-pop act Cocteau Twins, and Japanese folk bluesman, Kan Mikami, are, in some ways, poles apart. On the one hand, there is the otherworldly pop of Cocteau Twins, whose shimmering, reverb-heavy guitar ambience lifted the soprano virtuosity of Fraser in dream-like swathes of hypnagogic ethereality. And on the other there is the broken blues of Kan Mikami, whose sharp and jagged guitar twangs are held close to his strained vocal laments. But somewhere in the middle, between this broken bluesman and the ‘voice of god‘, in a place just like Tarkovsky was talking about, Fraser and Mikami meet.

I first saw Kan Mikami in 2007 at the Music Lovers’ Field Companion festival. I had never heard of him before then and I haven’t forgotten him since. His set was extraordinary, a kind of blues, country, folk and fado mashed together in a way I had never heard before (Mikami himself simply calls it Japanese blues). Partly this is because I had never seen a Japanese singer songwriter live before, so there was a fresh novelty in the set. But mainly it was his style: his guitar playing was as gentle as it was harsh, his picking would sweep from smooth notation to broken/half-played chords and his vocal was – that because of my lack of Japanese was felt only in its tone and phrasing – palpably pained, filled, it seemed, with sentimentality, regret and nostalgia. Diamanda Galás alongside Jojo Hiroshige and Junko (both of Hijokaidan) would also take the stage that day, as well as a number of other artists, but it was Mikami who rung in my ears the longest.

There is something very different that happens in one’s appreciation of a singer when one is not a speaker of the language in which they sing. Partly, there is a degree of alienation. It was clear when listening to Mikami, whose vocal is at the forefront of his pained expression, that a rich world of Kerouacesque encounters and wandering was passing me by. But like many of the other non-Japanese speakers in the audience, Mikami came at me another way. It was as if I didn’t need to know Japanese to hear the ghosts of – even if they were simply my own projections onto Mikami to make sense of him – the likes of Woody Guthrie, Neil Young, Bob Dylan, Son House and Lead Belly. Even though this was confirmed after the fact, having read about Mikami’s interest in the Beats and American blues, I could already sense it; I could feel the brutality and tenderness of his stories even though I didn’t understand the words he used to tell them. Everything I love about blues, folk and country was there and I couldn’t understand a word of it.

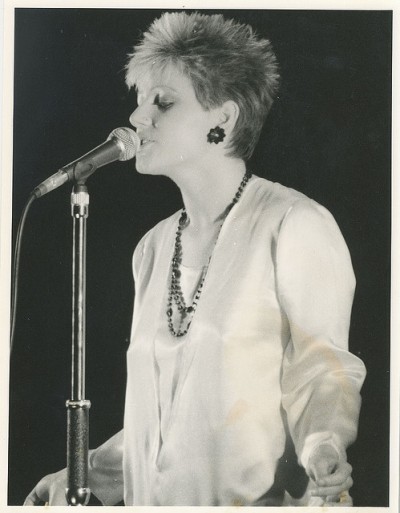

At the other end of this kind of experience is Elizabeth Fraser. In Cocteau Twins Fraser made a name for herself not solely because of her soprano vocal range but because she often sang without words. Fraser’s dream-like vocalisations would drift from language to non-language, words would frequently give way to nonsensical sounds and gestures. The result was, and remains, some of the most painfully beautiful pop melodies recorded that inspired generations of wannabe Fraser vocalists, all trying their hand at what would later be known as shoegaze or dream pop. The beauty of it all lies in the fact that Fraser didn’t need language to express emotion. It was as if she had tapped into the molten state of language right before it is solidified into words; all the feeling and beauty of poetry was there in arguably its rawest state.

Fraser is not averse to lyrics. One of her most recognised performances is her rendition of Tim Buckley’s Song to the Siren, as a guest vocalist in the collective This Mortal Coil. The song is a wonderful example of her vocal command, control and poise when it comes to the phrasing and delivery of lyrics. There are also fragments and pictures created by words in her own songs, but she has, admittedly, always struggled with them. As she puts it: ‘I can’t act. I can’t lie.’ This is why she prefers and arguably shines even more when she vocalises pure sound (sound without words). Unlike Mikami who is, by those who can comprehend Japanese, credited so highly for his lyrics and stories, Fraser’s plaudits came because of her interest in sound and her mastery of the voice as an instrument.

It’s my own ignorance and short-coming that prevents me from hearing Mikami’s lyrics. Until I learn Japanese, there will always be a story missed each time I sit down with this weary bluesman. But because of that I am forced to hear him differently. As Kelly Brunette writes: ‘You don’t have to speak Japanese to love the music of Kan Mikami‘ because his music is ‘composed of brutality and tenderness, angst, empathy and all that is ineffable and, as a result, crosses linguistic barriers.’ More than this, my lack of Japanese forces me to paint my own images and stories onto the empty canvas left by the lack of any recognisable words in my ears. The composition behind Fraser’s work is of course very different. There is, with Fraser, no language to be learnt and no story to be found. Yet the result when listening to these different but equally extraordinary artists is the same for me; I am left painting my own story, forming my own pictures and projecting my own feelings onto these blank canvases of generative sounds.

There is maybe a danger here, especially when it comes to Mikami. The danger is a kind of listening imperialism, an orientalism that looks to take what it wants from something culturally specific. After all, this music is, as Mikami tells us, Japanese blues. But what I am reminded of, somewhere between Mikami and Fraser, is Tarkovsky. Instead of any kind of cultural hijacking taking place, I am reminded of art’s blank canvas, of the incompatibility of the ‘have to be’ with art and the individuality defining each piece. I am reminded that even if I understood the words of Mikami, that wouldn’t mean I was any closer to the centre of his work because ultimately there is no centre of a piece of art. I am reminded that somewhere deep within language there murmurs the infinite multiplicity of interpretation, like the molten state of language from which Fraser takes her sound, which makes any fixed meaning impossible. I am reminded that you don’t need to understand language of any kind to enjoy music, language is just one way in.