When I phoned an ex-neo-Nazi skinhead for the first time several months ago, the prefix “ex-” somehow meant everything and nothing at the same time. In one sense, like the act of speaking over the phone, those two little letters and hyphen created distance, suggesting that the words following them and all they signify are in the past. And yet, part of me couldn’t quite shake the idea that, “ex-” or not, I was about to speak to a man who, a couple decades earlier, had subscribed to a white supremacist ideology every bit as hateful, violent, and repugnant as the scenes still fresh in my mind from the then-recent ugliness in Charlottesville, Virginia.

That ex-neo-Nazi skinhead was 49-year-old Chuck Leek. After we had spoken for a few minutes, my nervousness dissipated. Leek came across as soft-spoken, thoughtful, and warm. We joked together, and he described attending Dead Kennedys shows in the mid-‘80s in San Diego and forming a band to, among other things, get girls and burn off excess frustration. In many ways, it was like talking to an uncle or stepping through the DIY pages of Michael Azerrad’s Our Band Could Be Your Life. I almost forgot that I was speaking to a former prominent member of multiple high-profile hate groups (including White Aryan Resistance and The Hammerskins), a man whose violent, antisocial past had once sent him to prison for assault with a deadly weapon.

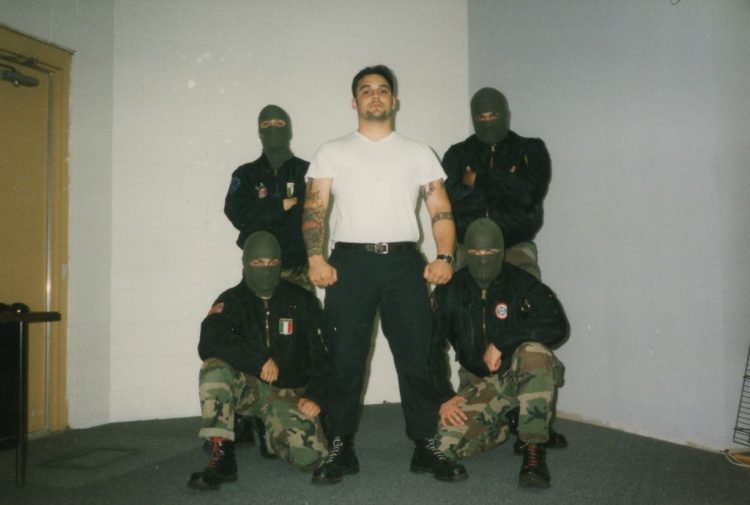

Christian Picciolini and Final Solution (Courtesy of Christian Picciolini)

Towards the end of our conversation, Leek asked me to wait a moment. He was digging for his only copy of the lone studio record by Battle Axe, the San Diego white power band he fronted in the ’90s. “It’s one of the few remnants I’ve kept,” he told me. I asked him how he reconciles a creative accomplishment from his youth – after all, not everyone has recorded an album – with the fact that it’s forever embalmed in such hateful ideology. “I keep the CD as a reminder of how disappointed I am in myself,” he explained, startling me with his frankness. “It’s not a memento of a positive time. There are a few things I still have to remind myself of the terrible choices I made. It’s been a while, but now and then, I listen to a bit of it and cringe.” In those few seconds, especially when imagining him hate-listening to his own angry songs from a lifetime ago, it became clear just how important the prefix “ex-” also is to a man like Chuck Leek.

One phone call to a former hate group member doesn’t make a thing like that old hat, of course. The following afternoon, I sat down to call another. I knew more about Christian Picciolini going in. In 2011, he had co-founded Life After Hate, a non-profit dedicated to helping people leave hate groups; Leek is in the program’s network. Picciolini had also penned a memoir in 2015, Romantic Violence: Memoirs of an American Skinhead, which has since been re-titled and updated. But even common threads — both of us are Chicagoans, writers, DePaul alumni, and we even know some of the same people within Chicago music and media circles — can feel tenuous when compared to the robes, patches, and flags that signify the ideological fabric of white supremacy.

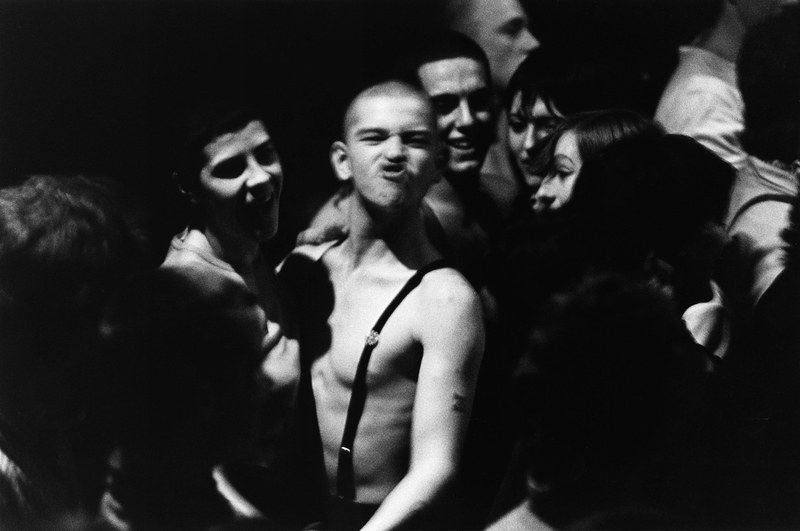

Final Solution (Courtesy of Christian Picciolini)

Picciolini spoke matter-of-factly, like a writer might. He knows his story, has told it on many occasions, and has clearly taken the time to get on his hands and knees, crawl around, and shine a light into the nooks and crannies of his past. One story he’s told many times, in both writing and during talks to various groups, finds him alone as an alienated 14-year-old smoking a joint in a dead-end alley at the intersection of Union and Division Streets in Chicago. (The irony isn’t lost on him.) He described himself at that time as ambitious but angry, with feelings of loneliness, abandonment, and confusion as the son of Italian immigrants struggling to find a sense of identity or belonging in both his grandparents’ Italian neighborhood and the white Chicago suburbs that his family lived in. The story continues with a muscle car ripping down that alley and coming to a screeching halt in front of him. A man with a shaved head and boots gets out of the car, pulls the joint from Picciolini’s mouth, stares into his eyes, and says: “Don’t you know that’s what the communists and the Jews want you to do to keep you docile?”

Read the full feature here at Consequence of Sound