This awesome feature was originally posted on the Epic Webzine RAREPEACE IG – Linktree Written by Sarah Von-H

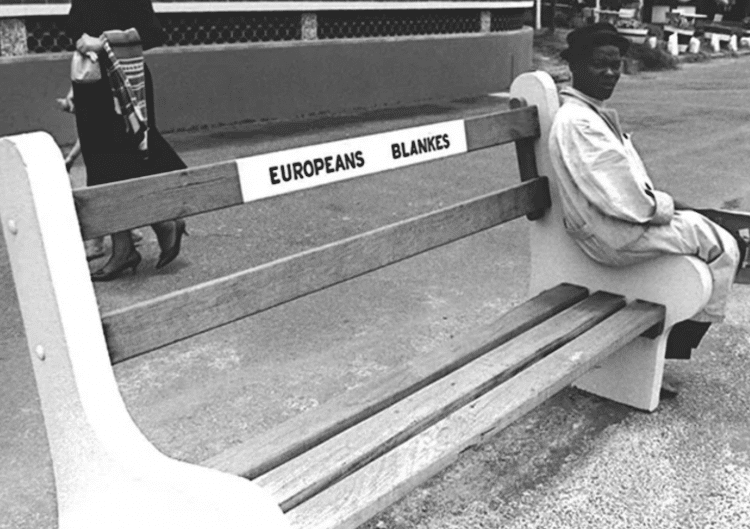

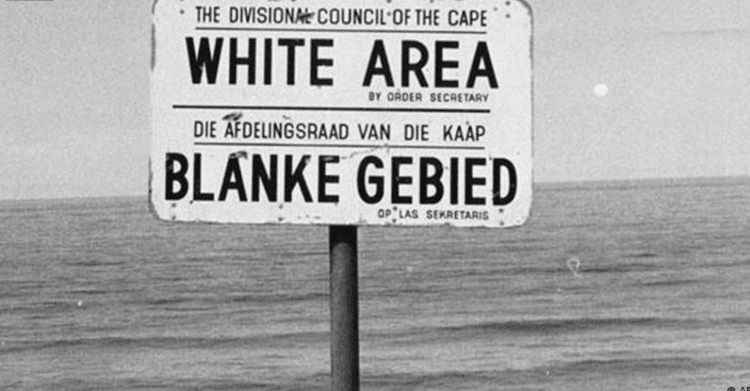

The history of South Africa is stained by the system of legislation that upheld segregationist policies against non-white citizens of South Africa also known as apartheid (“apartness” in the language of Afrikaans). After the National Party gained power in South Africa in 1948, its all-white government immediately began enforcing existing policies of racial segregation. Black citizens were dealing with great feelings of hopelessness and loneliness. There was always a reminder of danger around the corner.

This negative atmosphere led by the harsh political climate, contributed to the success of the uprising rave music movement in the early and mid-90s as there was an urgent need for change, temporary distraction, and peace of mind.

“While we found ourselves in a place of freedom where we could take drugs, meet many people, we also were incredibly obtuse about the life of black citizens in South Africa” – Charles Blignaut

The first known rave was in Piccadilly, Yeoville at an old cinema that was turned into a club. With numerous smoke machines, neon lights, and an over-the-top sound system they were able to create a historical event that is still relevant to this day.

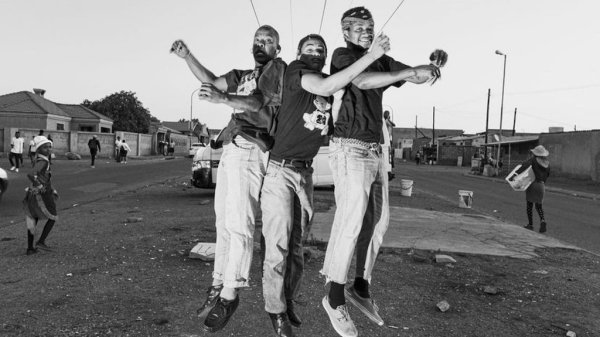

There was an overwhelming feeling of discovery in its own way; getting to know a black person for the first time and realizing that it’s actually great to be with each other whilst getting to know a white person and feeling safe around them. The mixed club scene in Yeovllle brought a multicultural change to the neighborhood which from 1990 to 1995 became a melting pot for the open-minded, curious, and tolerant. “The music brought the black boy and the white boy together. It has never happened before” – Vinny Da Vinci

White kids that grew up in super fascists racist family wanted to get away and start becoming part of the rave scene” – Dj Lakuti Many scholars have suggested that oral traditions such as poetry which was traditionally seen by some South Africans as a legitimate means of criticizing authority, and music, played a big part in the resistance. Oral traditions were in fact more accessible to a large number of South Africans compared to written material. Numerous protest songs emerged from these traditions.

The apartheid government greatly limited freedom of expression through censorship, reducing economic freedom and mobility for black people, as they were expected to racially segregate their musical endeavors. Mixed-race bands were sometimes forced to play with some members behind a curtain, and people who listened to music composed by members of a different race faced government suspicion.

Music scholar Anne Schumann writes that music protesting apartheid became a part of Western popular culture, and the “moral outrage” about apartheid in the west was influenced by this music.

We were exercising our freedom but escaping reality. We all accepted that we were new South Africans but not interrogating our whiteness and our past and what we continue to contribute to an unequal society.

– Charl Blignaut

Writing in the Inquiries Journal, scholar Michela Vershbow writes that although the music of the anti-apartheid movement could not and did not create social change in isolation, it acted as a means of unification, as a way of raising awareness of apartheid, and allowed people from different cultural background to find commonality.

The music played at raves was inspired by European sounds such as techno, jungle, breakbeat, and acid house as DJs were able to smuggle vinyl into the country when traveling back and forth to Europe.

Most of the music played at the raves (mainly remixes of popular songs), became extremely popular but was still not available for the masses to purchase due to apartheid restrictions in South Africa.

This fomented a strong need for music creation within the country which led to the foundation of Kwaito, a movement that broke all barriers and which is considered to be the sound of South African rave music by leading a post-apartheid township subculture into the mainstream.

The genre was born in the township of Soweto at a time driven by tension yet freedom as in 1994 Nelson Mandela took office as the first democratically elected president of South Africa.

Typically at a slower tempo range than other styles of house music, Kwaito often contains catchy melodic and percussive loop samples, deep bass lines, and vocals. The lyrics are sung, rapped, and shouted.

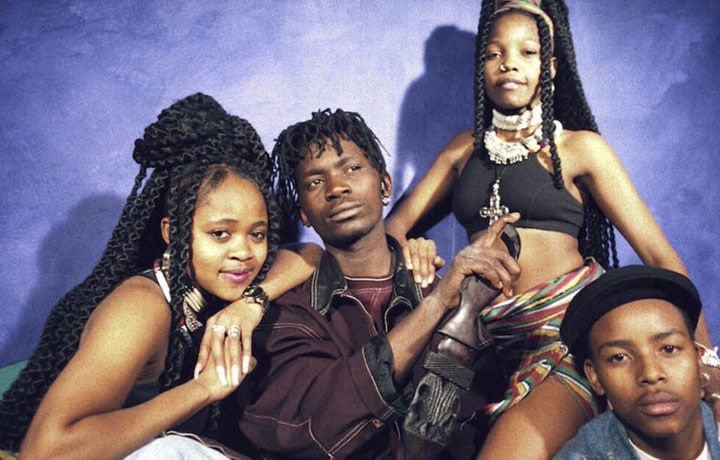

The word kwaito originates from the Afrikaans kwaai, a slang term that is the equivalent of the English term hot. Lebo Mathosa is known to be one of the main faces of the genre. She rose to fame as part of the group Boom Shaka, and later became a solo artist known by many as South Africa’s ‘wild child’ because of her sexually explicit lyrics and dance moves, she gained widespread popularity and performed at Nelson Mandela‘s 85th birthday celebration. Their first single “It’s About Time” was released in 1993 and their first album Kwere Kwere was produced in 1994. Her group Boom Shaka is considered to be a voice for young women and a symbol of empowerment pushing sexuality as an expression and celebration of black female bodies and the natural female sexual desires.

Very soon the name of Boom Shaka was tied to the political climate by trying to get women’s voices heard through recording a new South African anthem that simply says “women have the power to change the society”. The group offered women a new kind of agency in self-representation in post-apartheid South Africa.

It is safe to say that the removal of the political and economic sanctions greatly transformed the South African music industry.

AFRO-HOUSE AND THE EVOLUTION OF KWAITO

Afro House is a sub-genre of house music that mainly developed from South Africa. It is a blend of Kwaito, Tribal, Deep, and Soulful House music, and it is often seen as strands of Deep House or Soulful House, although it has its own unique sound.

It’s said to have originated in areas like Pretoria, Soweto, Johannesburg, Durban, and Cape Town.

Many years have passed since its inception but Kwaito still holds dominance in the music scene and it’s an inspiration for many South African DJs who understood the importance of the genre that currently influences their new sound.

Some Afro-house tracks may include a selection of vocals sung in an African language, while other tracks offer a blast to the past with the usage of old South African songs, lyrics, and folklores.

The genre can be divided in two different branches: the African tribal sounds (tribal-house, Afro-beats) and the other blending Chicago/NYC Soulful house with an African twist and a more vocal-led style.

Some of the main DJs and music producers that helped shape this sound by turning it into a global success are Black Coffee, Black Motion, Brian Temba, Chymamusique, Culoe De Song, C-Major, Darque, Deepconsoul, DJ Fresh, DJ Kent, Kaylow, Bucie, Siphiwe Mkhize (Enoo Napa), Jackie Queens, Wanda Baloyi, Echo Deep, Da Capo, Sir LSG, Tumelo, Lilac Jeans, Jullian Gomes, Derrick Flair, D.O.R. Projects, Gintonic, Octopuz, Zulumafia, House Victimz, Nastee Nev, Veneigrette, Young DJ, Rancido, Liquideep, UPZ and DJ Afrozilla and many more feature amongst the names associated with Afro House music.

Labels including Nulu, Rise, Union, MoBlack, and Vega Records have become the main point of contact by signing the majority of DJs and producers in the scene.