A woman walks through the dusty, grimy, street. It is packed with an immeasurable number of bodies, yet people seeking their ale still find her amongst the crowds due to her dark, peaked hat. She is one of the alewives in the community, producing enough overage from her family’s daily consumption to bring home extra income on market days.

In a few years time she is selling extensively out of her home. With the passing of her husband and the loss of his income, brewing becomes her only way to maintain independence. She mounts an alestake to her house as an advertisement to potential customers; the post is crowned with a sheaf of wheat to symbolize her wares.

The woman’s only companion is her a cat; it is as essential for company, as it is for protecting the grain-stores from pests. The cat will often warm itself by the large cauldron of cooling wort, moving when the woman comes to remove some of the frothing barm from the top of the pot. This yeasted concoction is added to a portion of flour, acting as leavening for the bread she will bake and eat that day.

It has long been suggested that the alewife (alternately referred to as brewess or brewster) served as the inspiration for the mass-media image of witches in the English-speaking world. In many areas of pre-Renaissance Europe, brewing was one of the few ways a woman could add income to the household. Particularly in Ireland and the British Isles, ale, hard cider, and small-beer were important commodities. Much of the water around growing communities was not potable due bacteria and waste, so low-alcohol beverages were an important source of hydration and nutrition. Women who were able to produce large quantities of ale in their homes could amass sizeable sums of money, some even surpassing what their male family members were able to bring home.

The ability of the trade to bring financial independence to women seems to have been one of the main reasons that its activities began to fall under scrutiny. As alewives’ homebrew operations grew into alehouses and pubs, they must have commanded extensive economic power. It is estimated there were 17,000 alehouses in England and Wales by the 16th century. Taken with inns and taverns, that equals about 1 drinking establishment for every 200 people.

This economic power was greatly undercut by the European guild system, who forbade women from roles of power in many of their charters. The merchant guilds began trade that brought hops to England. Continental-style beer was pushed as more sanitary, with hopped beer being a more “pure” product. With fear of the Black Death returning, cleanliness and shelf-stability were active selling points in the conversion to beer. Britain’s male-dominated brewers’ guilds begin incorporating Dutch immigrant brewers to their ranks in trade-port cities, and by the 1650’s, hops-based beer becomes a fully domestic product.

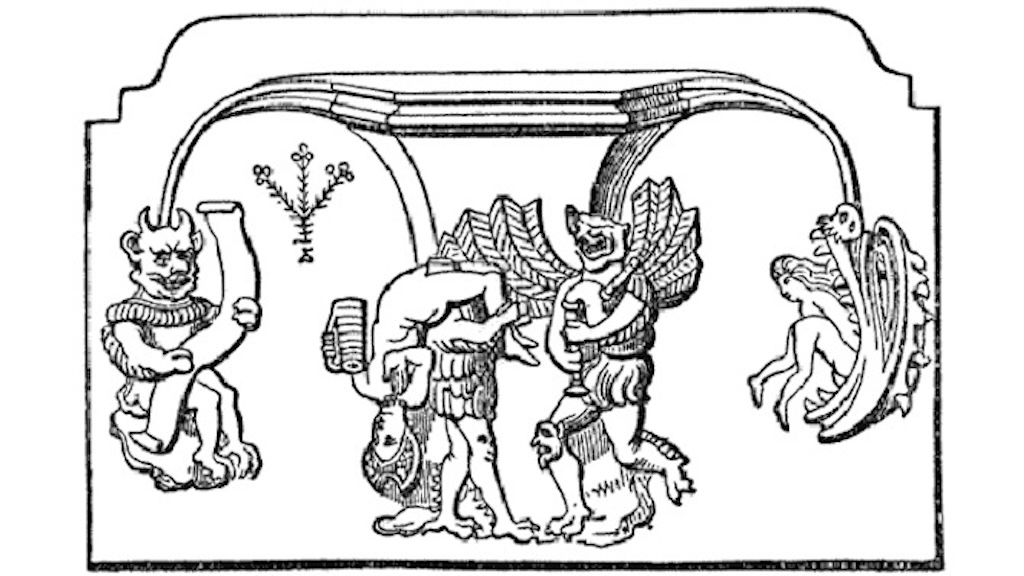

The guild system, with aid from the church, supported cultural depictions of alewives as cheats and sexually promiscuous. Images of alewives cavorting with, and being carried off by demons begin to show up in Doom paintings and church carvings around England in the early 15th century. Doom paintings conflate all sorts of “sinners” into the single group of the damned. Sinners were often represented in the nude; a viewer was meant to identify their transgressions by the symbols and attributes within the image. Depictions of nude witches riding household brooms appear in illuminated manuscripts as far back as 12th century, an image that could easily be conflated with an alestake aloft on a house.

Cats, too, saw a status change during this same time period. In medieval England, the keeping of small pets beyond burden animals and livestock was associated with the Cunning Folk, practitioners of folk-magic that used these familiars to aid in their practices. As Christian religiosity rose, households that used cats to protect their stores became suspect. Alehouses would have been viewed just as the homes of the practitioners of folk magic, indiscriminately swept up in a larger religious fervor.

The image of an alewife as a rowdy, conniving, woman was a common presence in the popular literature of the time. John Skelton’s The Tunning of Elynour Rummyng is a depiction of an alewife of this sort, selling ale doctored with chicken excrement that is purported to keep her customers looking young for their husbands. The poem said of Rummyng that, “the devil and she be sib[lings].” Skelton also recounts how she buys a charm from another woman meant to improve her ale yeast.

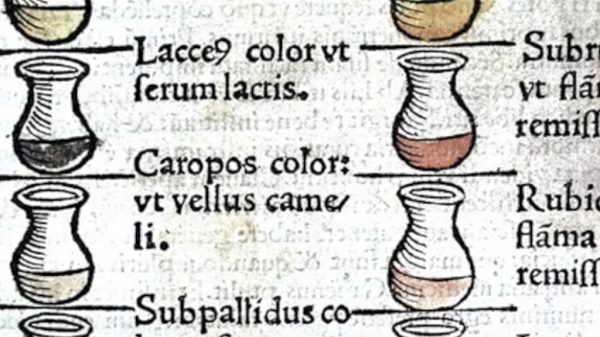

Originally written at the turn of the 16th century, Skelton’s poem first appeared in print around 1550, during the era of religious upheaval in Europe that gave us both the Reformation, Counter-Reformation, and the beginnings of the witch trials. The cover of a printed edition from 1624 shows Rummyng with a dark, pointed-peak, hat and a warted, curved, nose. This depiction of an alewife shows similarities to an image from another publication of the time, that of Anne Baker, an accused witch implicated by the Witches of Belvoir during their trial.

In the age of the Internet, images circulate and get modified, often without any attribution. We sometimes act like this is a new phenomenon, but it really is an issue as old as images themselves. Medieval Europe was a time when it was common practice to reuse woodblocks, reedition older prints, and copy works from existing sources, allowing iconography to shift meaning, just as today. It is easy to see how images of alewives, due to the vicinity they were placed with other targets of social persecution, could have their attributes conflated with witches. The power of images was exercised to its most negative ends–to marginalize, persecute, and consolidate capital for personal gain.

Read more about the history of women in brewing here.

NOTE: There is an equally plausible analysis of “witches garb” as tied to representations of Europe’s Jewish population in the Middle Ages. Whether this theory is the true origins remains unclear. What we know for sure is that the use of these attributes was designed as a tool to “other” populations and limit their power in society.