The sky has darkened

Thirteen as we are

We are collected woeful around a book

Made of human flesh– Mayhem “De Mysteriis Dom Sathanas”

Not only macabre inspiration for black metal lyrics or H.P. Lovecraft, one book published as recently as 1923 is rumoured to be bound in human skin. Perhaps the most famous example – and for many, the most macabre (that we know of) – is Marquis de Sade’s Justine et Juilette, bound in the flesh from a woman’s breast.

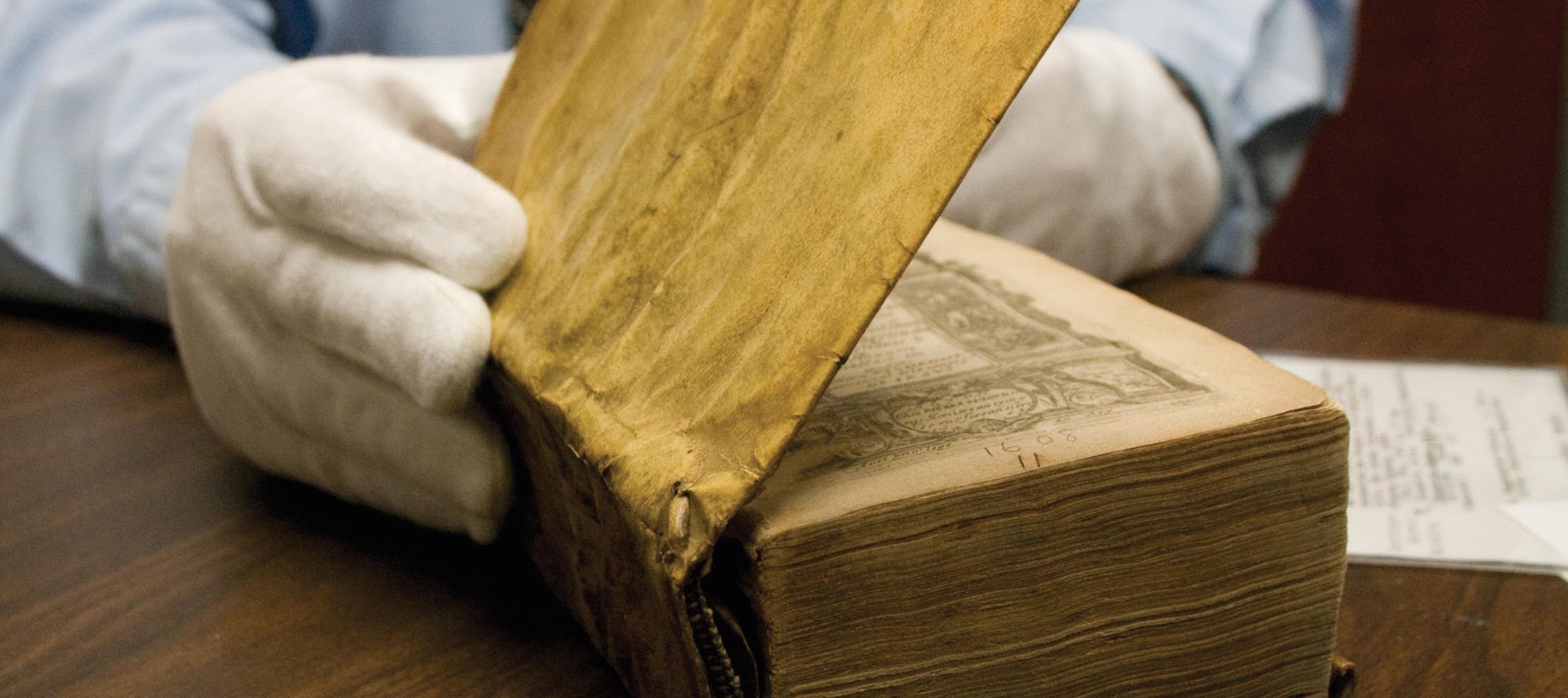

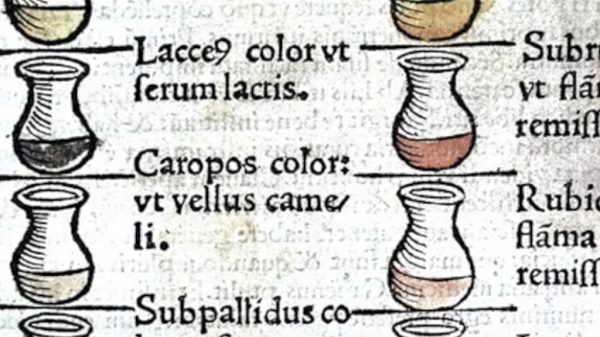

Though one may assume that these books are relics of a long past, a seeming majority of the ones rumoured or confirmed to be bound in human skin are much more recent, many from the 19th century. The intentions of the bindings vary. Some note that individuals, often criminals, volunteered their skin after death – which doesn’t seem too far-fetched, given the practice of gathering medical specimens from the corpses of dead criminals, and the fist-fights at the gallows over bodies. They may have known already what might have been in store for them after death, or already been ordered to be ‘anatomized.’ Although society was becoming progressively more secular, there may have been religious ideas of the body merely being a vessel for the everlasting soul, and acts of giving up one’s body after death, especially in the case of someone convicted of a crime, were considered a form of penance. Finally, there may have been practical reasons for some bindings: flesh is flesh.

Over the last few years, several American libraries have announced the presence of these books among their collections. Both the Houghton Library at Harvard and the lover of the macabre’s dream destination, Mütter Museum, have such books. Harvard’s copy of Arsène Houssaye’s Des destinées de l’ame is also one example, with the library stating publicly that the likely human origin of the binding was confirmed by several tests, and further noting that while other books in the university’s collection had been rumoured to have human bindings, with tests confirming that in fact, their bindings are sheepskin. Houghton’s copy of Houssaye’s book is dated from the 1880s, and its contents perhaps shed light on its choice of binding: it is a text on the afterlife and human soul.

Aside from the potential moral and ethical issues that might come up from such bindings, the usage of human skin in book-binding has some practical problems. Thinner than, for example, pig skin, the leather exterior is not as robust as that from non-human animal counterparts. Though it is unclear, and probably unlikely, that this practice continues into the present in the West, it did not take place on a large scale in the first place. Specimens from the 1800s are likely attributed to ideas of personal atonement for criminal acts, where the bodies of criminals were ingrained in systems of budding scientific research pre- and post-mortem. Whilst a book might seem loosely connected to research, two examples rumoured to be bound in human skin – Josephy Leidy’s collection of textbooks bound in human skin and an abridged Danish edition of A.E. Brehm’s Brehms Thierleben – involve subjects involving biological science.

Further Reading:

Heather Cole, “The science of anthropodermic binding”, Houghton Library Blog, http://blogs.harvard.edu/houghton/2014/06/04/caveat-lecter/.

Samuel P. Jacobs, ‘The Skinny on Harvard’s Rare Book Collection’, The Crimson, 2 February 2006.

M.L. Johnson, “Some of the nation’s best libraries have books bound in human skin”, Victoria Advoate 11 January 2006, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=861&dat=20060111&id=K-lYAAAAIBAJ&sjid=rVYMAAAAIBAJ&pg=5031,2157846.

Beth Lander, “Welcome to this inaugural edition of Fugitive Leaves”, Fugitive Leaves, http://www.collegeofphysicians.org/histmed/welcome/.

Navya S. Nambudiri & Vinod E. Nambudiri, “Anthropodermic Bibliopegy: Lessons From a Different Sort of Dermatologic Text”, JAMA Dermatol, January 2014, http://archderm.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1814819.