The term “colonial America” tends to conjure specific images, many of them unflattering.

Puritans.

Witch burnings.

The massacre of Native Americans.

One term that doesn’t usually spring to mind is “Bacchanalian revelries” – though that was exactly what 17th century travelers found when they visited Merry Mount, a small community just south of present-day Boston, Massachusetts.

Founded by the irrepressible Thomas Morton, Merry Mount (or “Ma-re Mount”) was a settlement dedicated to pagan traditions and unbridled celebration. The community began when Morton instigated an uprising of indentured servants, encouraging his fellow men to overthrow their masters and live as equals at Merry Mount. The settlers brewed beer, organized feasts, and befriended the nearby Algonquin Native American tribe. Perhaps as a nod to the community’s reputation as one long party, Morton proclaimed himself the “Host” of Merry Mount.

Morton’s colony outraged neighboring communities, especially Plymouth, a highly religious settlement founded by separatist Puritans. Among other things, New England Puritans opposed public drunkenness, dancing, premarital and extramarital sexuality, and religious traditions different from their own. All of these “sins” were business as usual at Merry Mount.

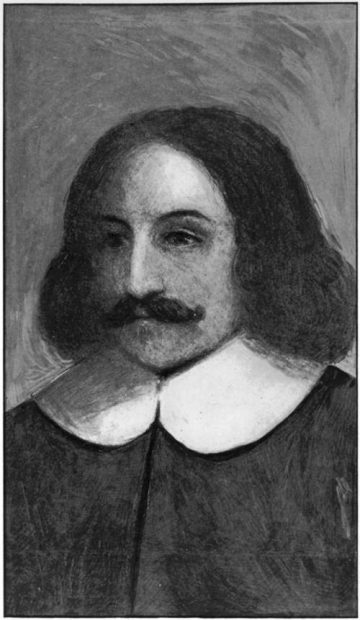

Governor William Bradford, enemy of Thomas Morton

William Bradford, then-governor of Plymouth, referred to Morton as a “lord of misrule” and the other residents of Merry Mount as a “wicked and [debased] crue.”

“Morton would entertain any, how vile soever,” Bradford wrote disgustedly in his memoir of colonial life, “and all the scume of the countrie, or any discontents, would flock to him from all places…”

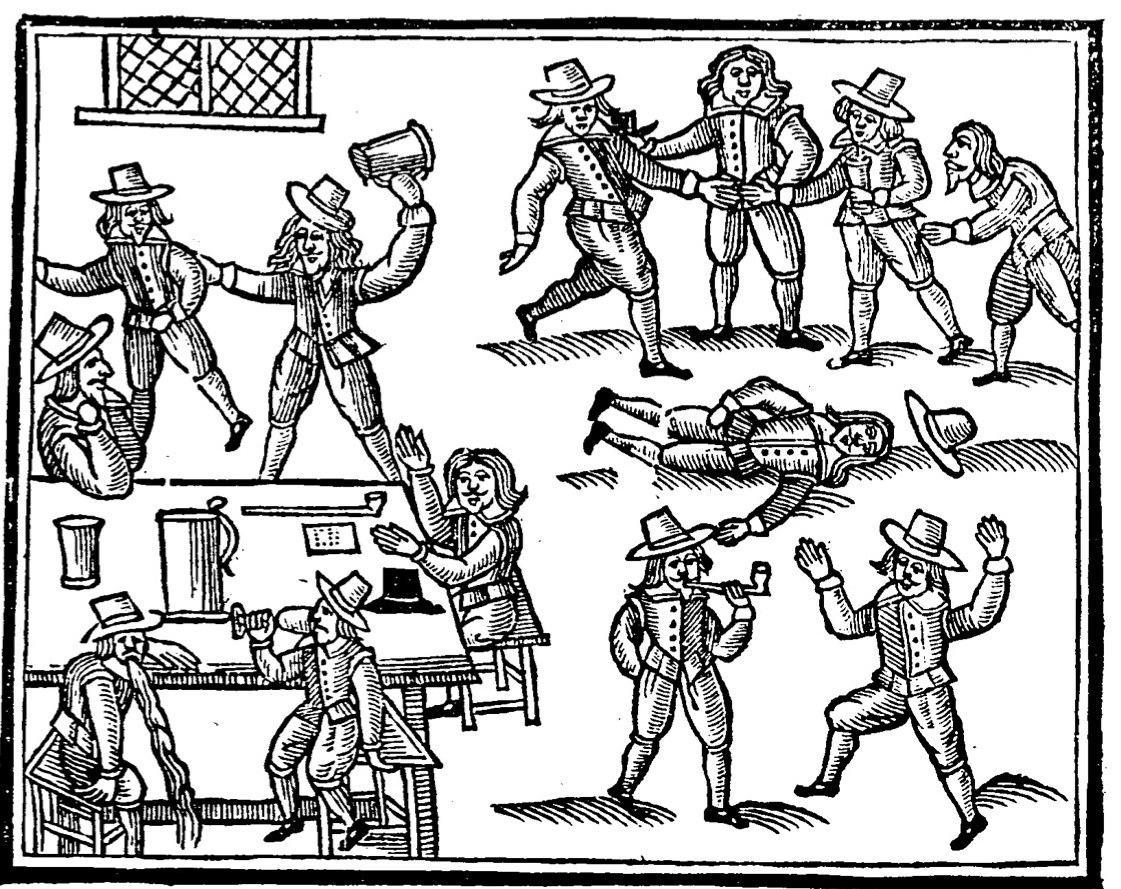

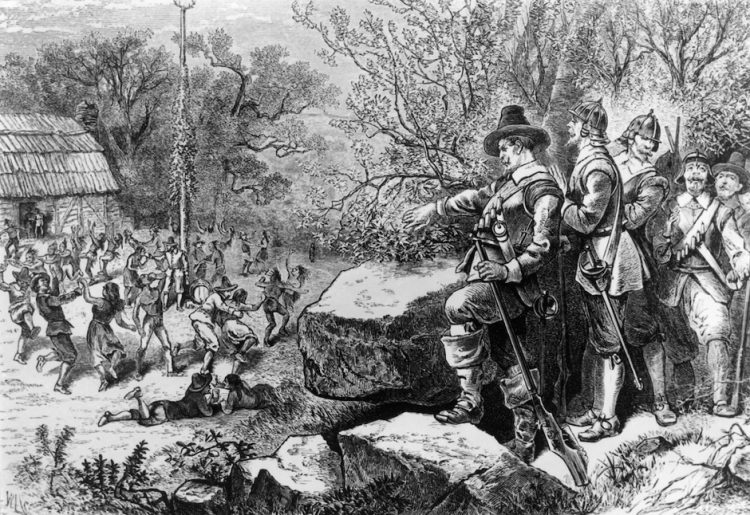

The conflict came to a head in 1627 when Merry Mount hosted a traditional pagan May Day celebration, complete with an 80-foot maypole topped by stag antlers. Morton wrote a poem calling upon various Greek and Roman gods and affixed it to the maypole, and, by his own account, members of the community danced “hand in hand” and drank “a barrel of excellent beare.” The group sang a song written especially for the occasion, with lines praising joy, women, and multiple deities. Most alarming to Governor Bradford, who decried the festivities in his memoir, the Merry Mount crew “invit[ed] the Indean women for their consorts, dancing and frisking together…and worse practices.”

It was the last straw for the Plymouth settlers. They developed a plan to destroy the festive colony and, according to Morton, “make it a woefull mount and not a merry mount.” In 1628, the settlers gathered a coalition of men from surrounding communities and charged Morton with selling guns to Native Americans. He was exiled and eventually sent back to England, but not before all of his belongings were seized and his home burned to the ground.

19th century engraving of Puritans encountering the maypole at Merry Mount

Morton, however, refused to be held down. He returned to the shores of Massachusetts less than two years after his exile, prepared to start anew. Startled by Morton’s return, the Plymouth settlers threw a barrage of legal issues in his path in an effort to prevent his regaining a foothold in New England. He was imprisoned and finally exiled to Maine, where he died circa 1647.

Merry Mount could have served as a model of possibilities – an alternative to the Puritan strongholds that made up the rest of colonial America. Instead, like its Native American neighbors, the colony fell victim to powerful people who destroyed what they could not control.