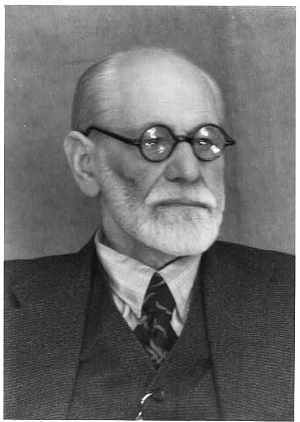

For good or ill, the theories of Sigmund Freud exerted an enormous influence on the 20th century, becoming deeply entrenched in Western culture to the point that Freud’s terms “ego”, “id” and “subconscious” have become common in everyday language. Within only a short time of its invention, psychoanalysis leapt from clinical practice into the world at large. In his 2002 documentary series The Century of the Self, Adam Curtis explores the application of Freud in the realms of advertising, marketing and politics. “This series,” Curtis narrates, “is about how those in power have used Freud’s theories to try and control the dangerous crowd in an age of mass democracy.”1

Utilizing a “trademark style” of “the contrast between commentary and image”2, between a bricolage of violence and chaos, and the reassuring and authoritative tone of Curtis’ narration, Curtis argues for the pervasive influence of Freud and his relatives throughout twentieth-century life in Europe and America. In four hour-long segments, Curtis recounts the impact of Freud’s theories “of human nature… [consisting of] primitive sexual and aggressive forces hidden deep inside the minds of all human beings. Forces, which if not controlled, led individuals and societies to chaos and destruction.”3 At its heart, The Century of the Self, concerns the impact and adoption of Freud, as the powerful wrestle with the basic nature of humankind, which Freud handily reduces to the idea of the id.

Utilizing a “trademark style” of “the contrast between commentary and image”2, between a bricolage of violence and chaos, and the reassuring and authoritative tone of Curtis’ narration, Curtis argues for the pervasive influence of Freud and his relatives throughout twentieth-century life in Europe and America. In four hour-long segments, Curtis recounts the impact of Freud’s theories “of human nature… [consisting of] primitive sexual and aggressive forces hidden deep inside the minds of all human beings. Forces, which if not controlled, led individuals and societies to chaos and destruction.”3 At its heart, The Century of the Self, concerns the impact and adoption of Freud, as the powerful wrestle with the basic nature of humankind, which Freud handily reduces to the idea of the id.

In the first episode of the series, “Happiness Machines”, Curtis argues that Freud’s American nephew Edward Bernays “was the first person to take Freud’s ideas about human beings and use them to manipulate the masses.”4 According to Curtis, Bernays introduced Freud into the world of marketing, targeting what he saw as the irrational and emotional realm of subconscious desire to coerce consumers into buying products.

While Bernays’ influence waned in the depression of the thirties, Curtis argues that the authoritative regime of Nazi Germany sought to channel human urges away from consumerism and towards the unity of the new state, as championed by the Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels – who even claimed inspiration from the writings of Bernays. The twin engines of business and politics, Curtis insists, were driven by the same fear and awe of the raw human desire of the human id.

The work of Adam Curtis is uncompromisingly controversial. His overtly argumentative stance, at odds with the dispassionate “both-sides” perspective of many documentaries, has placed him at odds with left and right alike. Apart from the core of his argument, the critic Jonathan Rosenbaum questions Curtis’ use of montage and filmic techniques, which Rosenbaum fears are in many ways analogous to the seductive marketing techniques Curtis himself criticizes.5

In fact, these very techniques of montage have placed Curtis’ work in something of a legal limbo, where questions of rights to music and clips have left his work marginalized in proper channels. Ben Waters carefully points out that this has left Curtis’ work in circulation in internet backchannels, often in painfully close proximity to conspiracy theorist videos, something which Curtis himself has been accused of indulging in. Yet, as Waters points out: “Although often described by detractors as a conspiracy theorist, his arguments in fact tend the opposite direction: he might describe history through narrative, but he doesn’t believe it has intentional authors… Ideas might shape the world, but those who have them or promote them seldom get the results they wish for.”6

Adam Curtis’ The Century of the Self is, above all else, an exploration into the power of ideas in contemporary thought. While Freud’s methodology and his conclusions have not largely held up to scientific scrutiny, their dangerous implications sent the men of power scurrying for a means to subvert and coerce by whatever means at their disposal. The widespread influence of Freud underlines the fact that ideas – even wrong ideas – hold enormous power over each and every one of us.