The revival of mystical philosophy, and, moreover, of transcendental experiment, which is prosecuted in secret to a far greater extent than the public can possibly be aware, has, however, set many old oracles chattering, and they are more voluble at the present moment than the great Dodonian grove. As might be expected, they whisper occasionally of deeds done in the darkness which look weird when exposed to the day. The terms Satanism, Luciferianism, Diabolism, and their equivalents, have been buzzed frequently, though with some indistinctness, of late, and in accents that indicate the existence of a living terror—people do not quite know of what kind—rather than an exploded superstition. To be plain, the Question of Lucifer has reappeared… It has reappeared not as a speculative inquiry into the possibility of a personal embodiment of evil operating mysteriously, but after a wholly spiritual manner, for the propagation of the second death; we are asked to acknowledge that there is a visible and tangible manifestation of the descending hierarchy taking place at the close of a century which has denied that there is any prince of darkness…this improbable development of Satanism is just what is being earnestly asserted, and the affirmations made are being taken in some quarters au grand sérieux. They are not a growth of to-day or precisely of yesterday; they have been more or less heard for some years, but their prominence at the moment is due to increasing insistence, pretension to scrupulous exactitude, abundant detail, and demonstrative evidence… Books have multiplied, periodicals have been founded, the Church is taking action, even a legal process has been instituted. The centre of this literature is at Paris, but the report of it has crossed the Channel, and has passed into the English press. As it is affirmed, therefore, that a cultus of Lucifer exists, and that the men and women who are engaged in it are neither ignorant nor especially mad, nor yet belonging to the lowest strata of society

– A.E. Waite, “Devil Worship in France”, 1896

In 1789, France erupted in revolution. The fuse which had been lit by the Enlightenment that promoted individual reason and rights over the sovereignty of Church and King had finally exploded as a result of extreme economic inequality, famine and debt, and it did so in a manner that took down the monarchy and threatened to lay waste to the Catholic Church as well. Unlike the American Revolution that was essentially waged against a foreign power, the French Revolution was a total upending of society from within. “Liberty, Equality and Fraternity” was the carrion call against a Monarchy and Church who cared only for power and the affairs of the bourgeoisie. As if to underline the difference in radicalism of the American Revolution versus the French, King George of England survived the loss of the colonies, while France’s King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were beheaded by guillotine and thrown into unmarked graves.

The Church faired only a little better. Prior to the revolution, not only did they have an overstated hand in governance, but they owned a fair amount of land, and collected a 10% tax on the population as well. For all of their abuses of power, churches were destroyed and priests were hunted and butchered during the “Reign of Terror.” There was a viable movement to de-Christianize France entirely, which was headed off by citizens who could not entirely forgo religion. In the end, the Catholic Church was still vanquished from the halls of governance and the separation of church and state was firmly established in France.

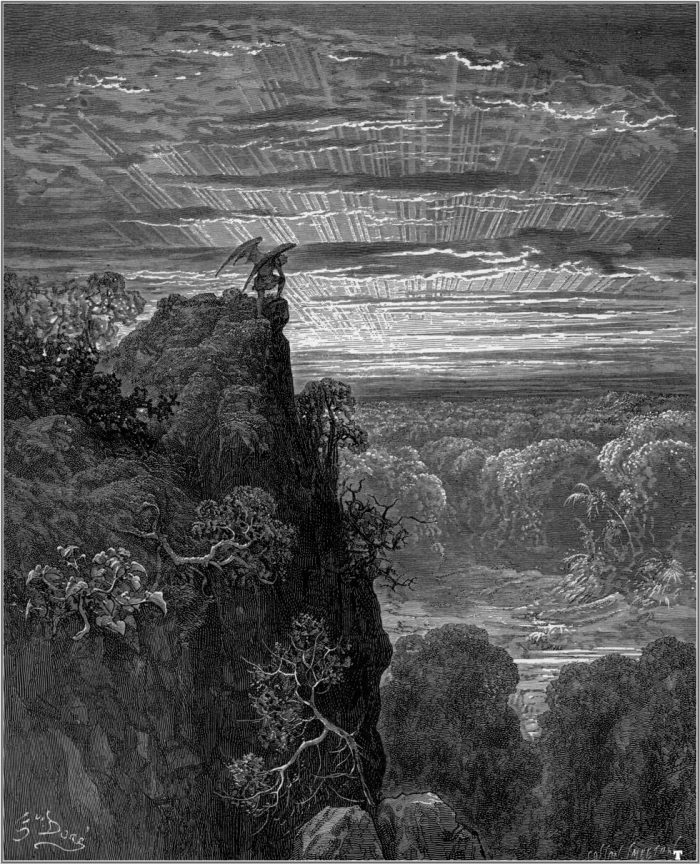

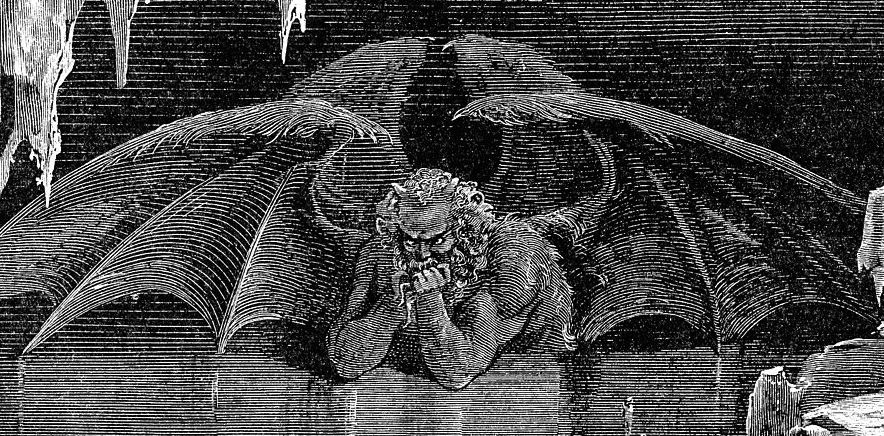

As could only be expected in the wake of such a re-ordering of society, shockwaves from the Revolution were still being felt in France over the next one hundred years (and arguably still inform French culture today). Riding those shockwaves was Satan, the liberating rebel himself, who found his way into art, literature, and religious and political intrigue throughout 19th and early 20th century France, starting with the English and French Romantics.

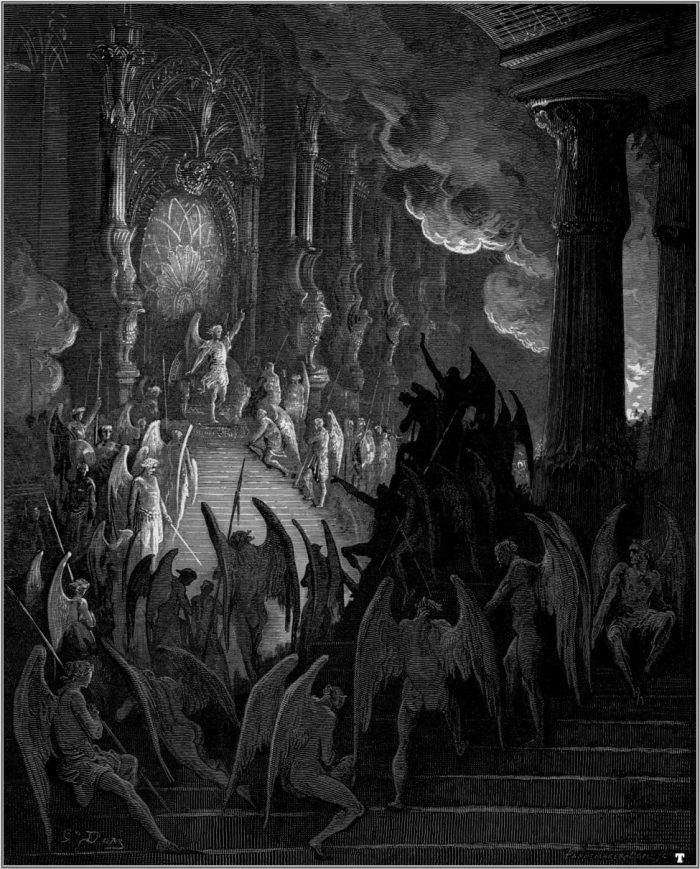

In the wake of the Enlightenment and its subsequent revolutions, Romantics such as Percy Shelly, William Blake, Victor Hugo and Lord Byron found themselves searching for new mythologies to fill the void left by the demise of the prior world order governed by divine sovereignty. They found it in the Dark Lord himself. Considering the Romantics were fascinated with myth and wonder while at the same time promoting the individual liberty and reason of the Enlightenment, Satan was tailor-made for their needs. Taking their inspiration from the Ruler of Hell in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, who was cast as an icon of freedom, reason and rebellion, these writers portrayed Lucifer Morningstar as the patron saint of man’s revolution against an absolute divine authority that cared little about the individual’s wants and needs, both spiritually and materially. So prevalent was their adoration of the Devil and his liberation theology that these literary giants were sometimes dismissed by more conservative writers as the “Satanic School.”

Although none of the Romantics who drew upon Lucifer for inspiration could properly be called “Satanists,” as there is no evidence that any of them participated in satanic or occult rites, their influence on those in France who were still fighting against the re-establishment and encroachment of conservative and religious forces cannot be underestimated, particularly by those individuals who would eventually marry active spirituality with the Romantic ideal of Satan. In part two of this discussion, I will turn to some of the personalities in French culture who danced with the Devil through more than just poetry, and who left an indelible mark on our current understanding of Lucifer and Satanism.