Originally published on Dec 13, 2016

The following is part one in a two-part essay on racism in the criminal justice system of America. This article will detail the policy decisions at a national level that have contributed to the institutionalization of racism in the American criminal justice system.

When I am not running around the woods black-robed and naked sacrificing virgins and infants under the light of the full moon, or immersed in ancient grimoires, I am wearing a suit and a tie defending the Constitutional rights of the most maligned among us – the outlaw, the criminal, the true misfit that has crossed a line that many of us know not to cross. To pay my bills, feed my family and fund my nocturnal occult proclivities, I work by day as a criminal defense attorney. I love my job because it is the one profession in America where I get to call cops liars to their faces, and rather than face retribution, sometimes, instead, I am rewarded for it (I once got a five minute not-guilty verdict from a jury in which my entire defense was, “this pig is a liar liar, pants on fire”).

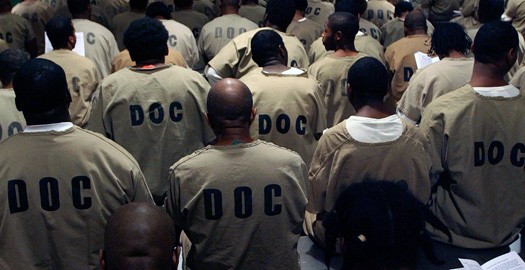

I also hate my job, because I see a side of humanity that is more broken, sadder and darker than any lyric of any heavy metal, goth or punk song could ever be. I live in that dark; its ooze long ago consumed my heart and soul, making me something more callous, more hateful and darker than I ever wanted to be – but also more awakened. The truest thing Anton LaVey ever wrote was that “Satan represents man as just another animal, sometimes better, more often worse than those that walk on all-fours, who, because of his ‘divine spiritual and intellectual development,’ has become the most vicious animal of all.” I work with vicious animals, both inside jail cells and out. Some wear orange, some wear blue and some wear suits. The American criminal justice system, based on alleged God-given “natural law,” is an exercise in (in)humanity at its absolute worst, and the fodder for this system, the meat that fills its belly, are the young black men of America. When Black Lives Matter takes to the streets and airwaves demanding justice and fair treatment, the problem is not, nor ever has been, with them; the problem is the radical disconnect with the white viewers at home who simply have zero frame of reference to even understand the genocidal threat that black America faces every time they leave their house at the hands of those that are sworn to “protect and serve,” the shock troops of a criminal justice system that seeks to grind them up and destroy every inch of their being.

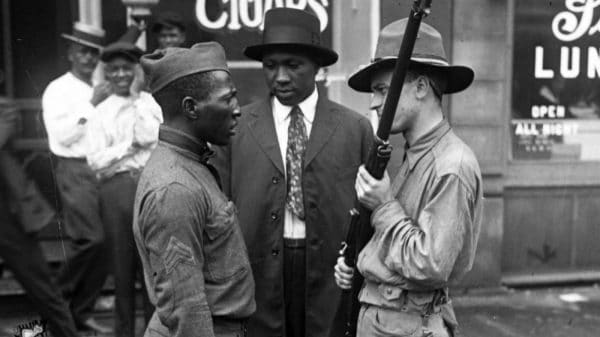

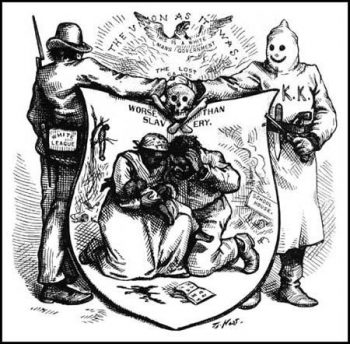

Before delving into the process by which this occurs, there are three socio-political and economic factors that undergird the system, ensuring that it remains a system bent on destruction, and not rehabilitation– despite claims to the contrary. For purposes of this article, I am not going to revisit the long and terrible history of racism in America. It is enough to say it is literally embedded in our bones. The birth of this nation included the enslavement, torture and murder of the black race (after, of course, the nation’s indigenous people). That racial wound has remained buried in the psyche of this country, sometimes manifesting itself outwardly more so than others. We are currently in a time where it is no longer buried at all, but a part of our everyday existence in a way it has never been in my lifetime. To pretend otherwise is to remain willfully ignorant of history, as well as current events. So, to use the language of logic, it is safe to say our nation’s racial history is the necessary cause at the basis of the current racial disparity in our criminal justice system, but there is also a growing list of sufficient conditions built on the long festering racial disparity at the heart of this country that has made matters far worse than they should be. To begin to understand some of these conditions, let us look at three legislative acts that occurred over the past 40 years that have ensured the institutionalization of racism at the heart of the criminal justice system.

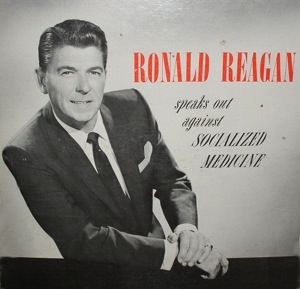

The first is Ronald Reagan’s campaign to defund mental health care treatment in the 1980’s. Continuing the same disastrous approach that he applied in California as governor, Reagan slashed funding to the National Institute of Mental Health as well as cut social programs designed to help the mentally ill. Most significantly, with the help of Congress, Reagan repealed the Mental Health Systems Act of 1980 that was signed into law by then President Jimmy Carter, which would have upgraded, reformed and guaranteed funding for the nation’s mental health care system. The net result of these actions was what became known as “Deinstitutionalization,” which is the process of closing up mental health facilities and/or moving those most in need of mental health care out of the mental health care system and into…well, nothing. There was no safety net at the end of Reagan’s rainbow.

The end result was an explosion of mentally ill individuals ending up homeless and untreated, placing them on the path toward a new form of institutionalization – the Department of Corrections. Since 1980, there has been a 780% increase in the American prison population. Stop and think about that number for a minute, if you can even process an increase in incarcerated individuals that large. This massive number is, in part, because the nation’s jails now serve as warehouses for the mentally ill – and what a warehouse they are. It should come as no surprise to anyone that other than receiving medications there is little to no treatment for the mentally ill in these prisons, and the mentally ill inmate’s inability to communicate with a staff who are not mental health professionals often leads to violent outcomes. As an attorney, I would say that approximately 1 in 3 of my clients suffer from some sort of mental health issue, and often I need the assistance of a trained psychologist to communicate with my client in order to come to a solution that isn’t simply throwing them back into the D.O.C. I know from experience that if you don’t have in place a mental health professional at the forefront of interactions with a mentally ill individual, nothing good will come from it. So when police or jail officials – who demand submission to their authority – interact with these individuals, nothing good comes from it. One particular incident stands out from when I was a very young lawyer, in which a welfare check was made on a mentally ill client in his basement apartment. When police arrived, the client became agitated – as even most non-mentally ill persons become when the police arrive at your door, especially if you are doing nothing wrong and there was no reason for them to be there. Rather than de-escalate the situation by bringing in a mental health professional, the police did what police do and used brute force to subdue the man. Instead of helping a mentally ill person that day, the police ended up tazing and beating up my client before charging him with Resisting Law Enforcement. The good news is that he didn’t end up dead, like Kajieme Powell of St. Louis did, or Ben Anthony C de Baca of Rio Rancho, New Mexico, or Alfred Olango of San Diego, or Kenneth Chamberlain Sr. of White Plains, NY, or James Boyd of Albuquerque, or countless more that I could spend the entirety of this article listing who were shot and killed by police who didn’t have the training, time or patience to deal with a mentally ill person, and decided murder was the only way to handle them.

But what does mental illness and the incarceration of untreated mentally ill persons have to do with race? Statistically, African Americans are 20% more likely to suffer from mental illness than the general population. One of the reasons for this are the social conditions that lead to childhood stress suffered by those subjected to poverty and violence. Recently, the CDC determined that 30% of children living in the inner city suffered from PTSD, or what the not-at-all-racist-as-fuck doctors at Harvard called “Hood Disease” (because the term PTSD was apparently too equated with white military veterans to sully it by including black children on the list of sufferers?). Even if you aren’t living in a “constant war zone” as the study articulates, the barrage of constant racism takes its toll on the African American psyche as well, according to health care professionals. In the end, not only is American society a threat to the physical safety of the African American community, but it is also a psychological threat as well. All of this is compounded by the lack of resources in African American communities to treat mental illness. Because of Reagan’s attack on mental health care, it now takes out-of-pocket money and insurance to treat mental illness, something that historically economically disenfranchised communities simply do not have. The end result is that once an untreated person commits a crime due to their mental illness, the criminal justice system is left to sort out mental health care for these individuals, something it is often not equipped to do.

The next piece of the racist puzzle is Bill Clinton’s 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, a bill so bad that even in this sharply divided political climate legislators at a state and national level have recently worked together to roll back many of its most harmful elements. This is the same bill that haunted Hillary Clinton on the campaign trail earlier this year when she was reminded that she had called young black men “superpredators” in a 1996 speech in support of her husband’s atrocious crime act. The Clinton crime bill did a lot of things, but the two main prongs of it were the increase in prison sentences and the increase in the number of police officers on the streets (the latter of which will be the subject of part two of this essay).

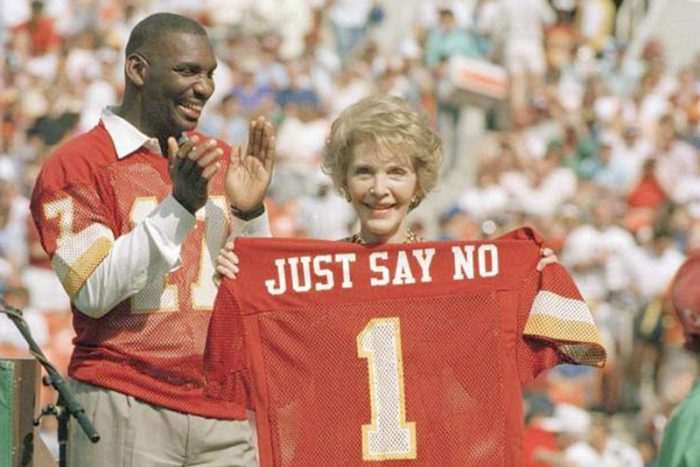

Clinton’s bill did not come out of a vacuum. Starting with Reagan, politicians’ go-to on the campaign trail was to be “tough on crime,” allowing for little to no nuance in addressing the nation’s rising crime rate (a rate whose increase, it should be noted, was one of the greatest results of Reagan’s defunding of mental health care in the country). Democrats and Republicans responded at both the national and state level implementing harsher sentencing laws and increasing the criminalization of acts that had previously either not been crimes, or which had been minor infractions or misdemeanors. This all dovetailed nicely with Reagan’s “War on Drugs,” and in concert these two legislative trends worked together to harshly punish drug users – black drug users specifically.

If there was any doubt that racism was baked into the system at this point, one need only look at another gem from Reagan’s greatest hits called the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. The law created a disparity in sentencing guidelines for crack cocaine and powder cocaine, which imposed the same penalties for the possession of an amount of crack cocaine as for 100 times the same amount of powder cocaine. And why? Because crack cocaine was cheaper and more popular in the black inner city than it was in the affluent bungalows of Hollywood. Cocaine was everywhere in the 1980s, but whether or not you were going to lose your life over using it depended on what color you were and what kind of cocaine you could afford. It was only in 2010 with the Fair Sentencing Act that this disparity was finally addressed. In the time in between, African Americans were six times more likely to serve lengthy prison sentences than whites for using what is essentially the same drug.

Maintaining and building on Reagan’s legacy, Clinton’s crime bill created more prisons, criminalized gangs (freedom of black men to associate be damned), ended higher learning in prisons (ensuring a move away from the “Corrections” aspect of the Department of Corrections towards the use of the penal system strictly for punishment), and also created the three strikes rule that sought to harshly punish repeat offenders. This last provision was replicated in many states, leading to injustices like that of Leandro Andrade, a 44-year-old father who stole videotapes of “Snow White” and “Cinderella” for his kids’ Christmas presents, and who, as a three-time felon, was handed two consecutive sentences of 25-years to life for the theft (because, as noted before, simple crimes like theft were now elevated to felonies as a part of the “get tough on crime” movement). Indiana, the state in which I practice law, has a habitual criminal enhancement, which is our version of the three strikes law. Recently I had a client who was arrested for something he did not do. The case was eventually dismissed, but while it was pending there was a no-contact order in place between him and the mother of his children (the crime he was accused of took place at her residence, and even though it was not a domestic crime, the court still put into place a no-contact order). While in custody, my client called the mother of his children, because she was the mother of his children and he was checking on his kids. The state discovered the calls and charged him with a felony for violating the no contact order. They also threatened to file the habitual offender enhancement. In total, he was facing 9 years for making a non-threatening phone call to his kid’s mother. That’s Clinton’s crime bill legacy.

The net effect of these “tough on crime” policies was to criminalize more acts and increase punishment, while decreasing the likelihood of success for a convict re-entering the community, which led to an increase in recidivism. This wiped out entire generations of black men from their communities. It is not uncommon at all for me to represent young black kids whose fathers were long ago consumed by the system, and without whom, they turn to the streets for an education on how to be a man.

Compounding these issues is the greater economic story of America, which is the third and final pillar that ensures that most inner-city black Americans remain in a cycle of poverty, crime and institutionalization in our nation’s jails and prison. There is narrative out there that the North American Free Trade Act of 1994 hit the small towns of America the hardest. For sure, it is true that one of the many effects of NAFTA was the death of many small communities that lost manufacturing jobs. I am from one such community and I have seen the ravages of NAFTA first hand on the “white working class” that has been the obsession of so many in the media of late. What this narrative misses, though, is that it wasn’t only small town whites who perished under the blade of free markets, but also blacks and whites in the inner cities. The area of the highest crime rate in Indianapolis used to be a quiet working class community. Blue collar workers of all races went to their jobs at RCA, GM and Ford, came home, raised kids and were able to provide a future for their families. Now, the east side of Indianapolis is a shooting gallery populated by abandoned warehouses and empty factories. The words “shooting on the east side” is as expected and as common as the weather report on the local news. Many of the whites have long ago moved out, although some of the proud and stubborn ones remain. One thing unifies them with their black neighbors, and that is they are all trying to cobble together a living with very little resources to work with.

The National Institute of Justice has determined that two factors reduce the risk of recidivism for a convict returning to society: the first is employment and the second is whether or not they are returning to a “disadvantaged neighborhood.” The effects of NAFTA have turned most previously stable working-class city neighborhoods into “disadvantaged neighborhoods,” to say nothing of the job prospects that await ex-convicts. In the past, a convict could re-enter the work market more easily through a low skilled blue collar job and make a decent wage doing so, now those jobs are gone and no one is bending over backwards to hire felons, or at least hire them at a living wage. The end result? Poverty or a return to a life of crime.

Yet as noted, NAFTA has had a similarly ruinous effect on small town white America as well, which, similar to the inner city, has seen an increase in drug abuse and crime. But what poor white Americans do not face are the racially targeted effects of the Reagan and Clinton crime bills, as well as the most immediate manifestation of racism in the criminal justice system – the police themselves. In part two of this essay, I will focus on the Clinton crime bill’s most lethal legacy: the over-policing of America’s city streets.