via Fact written by David Katz

Fronted by an intense singer with an oblique songbook and a mysterious past, Glorious Din were unlike any other group to emerge from San Francisco’s ‘80s underground. David Katz tells the story of Eric Cope, the chosen persona of a Joy Division-obsessed Sri Lankan boy who travelled halfway around the world to follow his punk dream.

The early 1980s was an incredibly fertile time for underground music in San Francisco. The scene was centred on a troop of interconnected bands playing at alternative spaces to small but devoted audiences – an antithesis to the stadium status achieved by the local rock acts of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

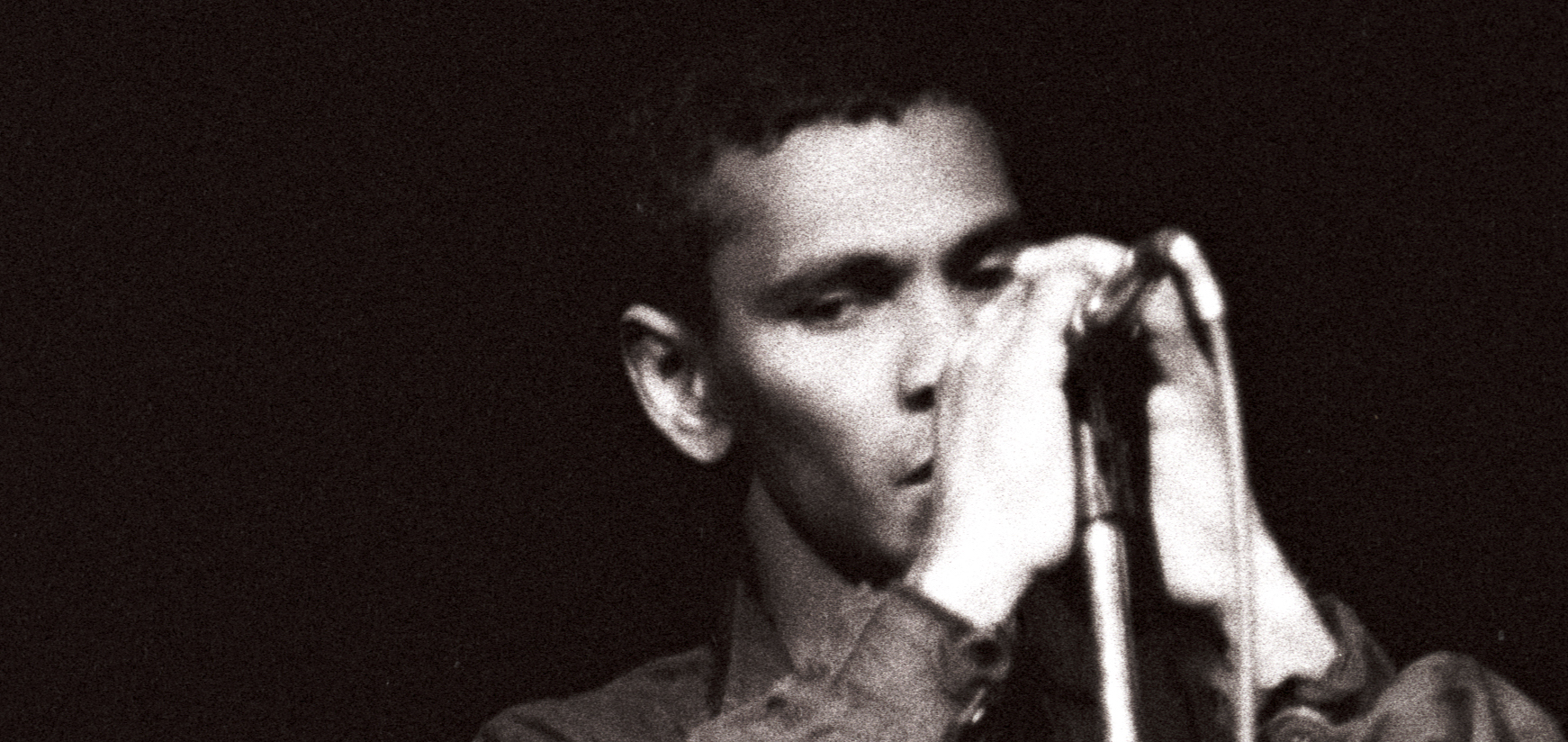

The multifaceted nature of the ‘80s scene – encompassing everything from three-chord thrash punk to garage-band pop, experimental art rock and atonal noise, all created by bands with overlapping memberships – can seem baffling to outsiders. Of the many acts clamouring for attention, Glorious Din was perhaps the best, their mesmerising sound instantly getting under the skin via their non-standard drum patterns, eastern-sounding guitar melodies, a melodic bass in pole position, and a dissociative foreign singer who intoned prophetic poems in a trance. The enigmatic group acted as a catalyst too, helping total unknowns to gain recognition and being the uncommon glue linking Faith No More, the Dead Kennedys and Michael Franti, as well as REM and the Cocteau Twins, such is the reach of their influence.

The tech giants of Silicon Valley have since turned San Francisco into a boutique yuppie playground, but the city was a transient place back then, characterised by low rent, cheap drugs, and radical social activism. Its overarching permissiveness made it a haven for misfits and dropouts rather than microchip prospectors brokering the latest dating app. The music of the ‘80s counterculture thrived in peripheral spaces, and part of Glorious Din’s appeal was their mysteriousness: a quartet of mismatched musicians not necessarily playing their chosen instruments, with the obscure lyrics of their intense frontman near impossible to decipher. The group imploded after only three years, but their cult appeal has lasted far longer through their two albums and related material on their Insight label.

Tracing the band’s backstory is no easy feat, since the lead singer and chief shape-shifter, Eric Cope, is central to the tale. Back in his native Sri Lanka, Eric was a barefoot boy with a Sinhalese name, born after the appearance of strange omens: a solar eclipse, the unexpected arrival of a helicopter, and a sleeping cobra on a train. His mother knew he would be different from everybody else and that he would have a gift to give, and her belief had a big impact on him. The young boy grew up with wild animals and birds all around him in the dry zone jungle of Polonnaruwa, in the North Central Province of Sri Lanka. The most important influence in his life then was the local shaman, Appu Hamy, who became his mentor, telling him Buddhist Jataka stories and other folk tales, and teaching him pal kavi chants while collecting the bones of animals that had been devoured by leopards in the night. Tin Tin comics were another early source of inspiration, and his mother played local music on the radio continuously. But everything changed when he was eight years old and his family moved to the urban environment of Galkissa, a beach town outside Colombo.

“When my parents moved to the city, I felt like a noose was around my neck, and I felt it get tighter and tighter,” he recalls. “I was not in the jungle, so there was something missing in my life, and getting into trouble, and comics, was how I filled that empty space. By the time I was 15 I was a seasoned thief, moving in and out of crowded markets and stores, stealing whatever I could, but I mostly stole books and comics. And the thief was born because of the destruction that happened to me after my parents moved to the city. I was alone, an out-of-place outsider, so I would just move about in the street to see what I could steal. I didn’t want to get into trouble, but I did.”

Soon he would endure school suspensions and a jail term. “In 10th grade, when I was 15, I was getting another beating by a priest, who later became the rector of the school. I had enough of all that, so I got a hold of the cane, broke it in two, and hit him back. He fell and hurt himself, and I got suspended from school for three weeks. Then, a few months later, I was riding a bus and hadn’t paid the fare, and I got caught. The conductor was trying to take me to the police station, so I hit the conductor with his ticket machine. I went to jail for this, and got expelled from school.”

After his release, he worked as a gravedigger and then in a fiberglass boat factory. A visit to a village ‘dentist’ resulted in the loss of eight teeth in a near-death experience. He encountered Bob Dylan in the 1972 Concert for Bangladesh film, about the benefit gigs put on by George Harrison and Ravi Shankar, which inspired him to buy a guitar and become a folk singer. Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout, the 1971 film about siblings left to fend for themselves in the Australian outback, also had a profound effect on him. And crucially to the next stage in his story, his family hosted a 16-year-old girl from Bettendorf, Iowa, for a few months; he made music with her too.

At 19 years old, with a strange working class English accent picked up from John Peter Jones’ Brixton-set book The Feather Pluckers, he travelled to the emirate of Sharjah where he worked in a pet shop run by a Palestinian. The conditions were exploitative; his employer retained his passport, making him work 14-hour days under the threat of deportation, and after three weeks he lashed out at his boss and fled. Thankfully, a friend who worked as a cook on a Greek ship got him a job as a ‘house boy’ for some Dutch construction workers lodging at a local guest house. “The Dutch people loved me,” he says. “They were only a year or two older than me, and we all liked the same music – a lot of early punk, Elvis Costello, Joe Jackson, and the Eagles, Beach Boys and the Supremes.”

His Dutch companions subsequently arranged for him to get a visa, sponsoring him to go to Holland for a time. There, he wrote to the exchange student from Iowa who had stayed with his family in Sri Lanka, saying that he wanted to come to America. Her parents made arrangements for him to travel there, where he attended a local chiropractic school and soon met a young woman named Jessica Lea. Although she was already pregnant with another man’s child, they quickly married.

“When our boy Bruce was three months old, we went to Philadelphia,” he continues. “I was going to go there and start a punk band, and we lived in a $5 hotel in the poorest section of Philadelphia for four or five months, and when our money ran out Jessica Lea’s sister and her husband rescued us—they sent us two airline tickets to Alaska, so we lived in their trailer in Big Lake where they were homesteading. Then Jessica Lea got a job as a hotel maid in Anchorage, so we moved to Anchorage and I got a job in the planning department as a graphic tech. I mostly drew maps and delivered them to the clients.”

It was in Anchorage in 1980 that he took on the persona of Eric Cope. “The name Eric I got from a book and film called Fade To Black, where the main character is called Eric Binford,” he explains. “He’s a true loner, an outsider, who was similar to me in every way—he didn’t belong anywhere, so he was absorbed in his own world. The name Cope I got from Julian Cope, who sang with the Teardrop Explodes—a name I also knew from a Daredevil comic I had in Sri Lanka.”

With the name change, Eric Cope switched his wardrobe, and went from dressing like a skinhead to wearing a fishtail parka given to him by an Inuit in the streets, which made him feel like one of the mods in Quadrophenia. But his life was as unsettled as ever. “Our marriage was falling apart—very sad times. We were listening a lot to Neil Young, and Donovan’s A Gift From A Flower To A Garden. Jessica Lea left with Bruce, our boy, for the first time, and she left many more times after that, but kept coming back. I got fired from my job in the planning department, so I decided to go to New York to get a punk band going. But then Jessica Lea said for me to take her and our boy to Iowa first, and I ended up with her in Davenport again. Then we had another son, who I named Ian after Ian Curtis of Joy Division.”

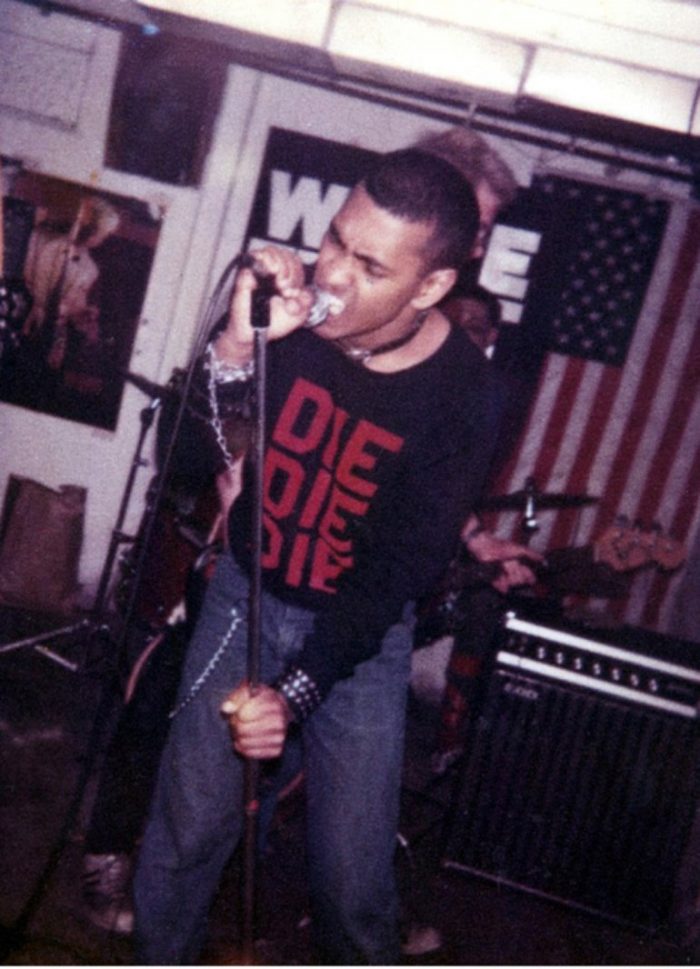

By 1981, Cope was in a hardcore punk band called White Front, formed with another singer called Tim Storm, who had placed an ad for musicians at local shop Co-op Tapes and Records. “We both sang and we mostly did songs by Circle Jerks and Black Flag, but faster than how they do them,” he says. “We also did Buddy Holly and the Doors and Beach Boys, but we did these songs faster than Circle Jerks or other punk bands. We had Eric Larson on bass, then Doug Heeschen joined on guitar, and I started to write a lot of songs then.”

“The name White Front was Eric’s idea, because he thought it sounded racist and fascist and would get attention because he was black,” explains Heeschen, the Davenport native who would later play bass in Glorious Din. “They wanted to play the Clash, Dead Kennedys, Black Flag, the Dead Boys—anything loud, fast and bratty. They teamed up with Craig Caldwell, a high school kid, and Eric Larson, a former professional cyclist with a troubled family history. I was the only one who could actually play an instrument, but we found a sound that worked enough to get some basement shows, and a show at the local gay bar. We practiced in Eric Cope’s rented house in the east side of town, and the cops came to shut us down pretty often in the summer when the neighbours had their windows open. The Unitarian Church in Iowa City was a focal point for punks in eastern Iowa, because it was in a college town, but they only let us play once we convinced them Eric was the singer, and they wouldn’t let us put the name on the poster for the show.”

Heeschen was raised among the suburban cornfields and joined a rock covers band as a high school student, but switched focus after being exposed to the Sex Pistols and the Ramones in 1978. Instead of taking up his probationary placement at MIT, he decided to pursue music, and says that Cope made an immediate impression. “When I first met Eric Cope, I thought he was on the verge of exploding. He had a wide smile, and when he got excited he would almost shake. He also had a dark side that came out after a beer or two, and we were always watchful to make sure he didn’t start any trouble that would get him locked up or killed. He was impatient, smart, philosophical, and driven to music to a ridiculous degree. I was impressed about how little he cared about anything else—music was everything.”

Within a year White Front had been banned from every local venue, so they decamped to San Francisco in August 1982 at the suggestion of Tim Tonooka, publisher of Ripper magazine. Their drummer stayed behind in Iowa, so a Rough Trade ad brought in Bay Area native Pete Herstedt, who had played guitar in Santa Barbara punk band the Generators and was also competent on drums. “Pete was a solid drummer with a simplistic style that worked well for us,” says Heeschen, “but he was mysterious and never let us know where he lived or worked. He was trying to keep his home life separate from his band life, so it took years to figure out even simple details about him.”

Local venues were wary of hosting White Front because of their name, and artistic disagreements cause a rupture in January 1983. “Eric was listening to a lot of Joy Division and Killing Joke, and he wanted to move the sound that way, while Tim wanted things faster,” says Heeschen. “So when we wrote songs it was half of one kind and half of another.” Storm, Heeschen and Herstedt splintered to form the garage-rock Koel Family, and Cope and bassist Eric Larsen started the psychedelic Other Voices, which soon split. Cope then began playing with guitarist Jay Paget, who’d left his native Boston to study journalism at the University of Oregon, only to spend a couple of years hitchhiking all over the West.

“I wanted to get as far away from Boston I could get, physically and culturally,” remembers Paget. “So after a final drunken night in Boston going to a Marshall Tucker concert with my friends, I flew to the West Coast. I can still recall my first glimpse of Eugene and the sinking feeling that accompanied it as I stepped out of the airport into the grey skies and the air filled with the smell of the paper mills of the Pacific Northwest. I didn’t know anyone in Eugene so I spent a lot of time teaching myself to play guitar – just before I left home I grabbed my brother’s guitar, without asking him. At the time, my musical influences were holdovers from high school and FM radio, like Springsteen and Billy Joel. I lasted only a couple semesters at the University of Oregon. I had met a bunch of freaks who were very entertaining and none of them in school, and I willingly followed their lead to places I later thought I never would have gone if I had only known.

“After a couple years I struck out on the road hitchhiking with absolutely no plan other than seeing where things would take me. I would stay in towns for a few months, work a bit, then head back out on the road. I either gave away or sold everything I owned. A woman from Davis, California, gave me a white Ovation guitar that I would tout around and play while waiting for rides. I was not listening to the radio and did not have much of a sense of what was happening musically. Being on the road was a choice, so I can’t really say I was homeless, but I must say I fully removed all of the usual safety nets like a home, money and a circle of friends to rely on. I landed in San Francisco in 1982—the proverbial end of the road. I was tired and wanted something different, all my belongings could fit into a Converse gym bag. I had tricked with a guy named Max who was happy to put me up until I could get a job. I made a few friends in town and eventually the circle widened to the point where I met folks in a band named Radio Free. They introduced me to the Mab and Club 181 in the Tenderloin, which looked like a cross between a gangster bar and a bordello.”

Read the Rest of this AMAZING Feature HERE!