When Cortez and his conquistadors arrived on the coast of Mexico in 1519, never before having seen or heard of tattooing, they were horrified to discover that the Indigenous people not only “worshipped devils in the form of states and idols,” but had somehow managed to “imprint indelible images of these idols onto their own skin.” Body modification wasn’t just seen by the ancient Maya as a way to sculpt the body, but also to improve it. The pliability of human flesh, bone and form allowed for an extension of Maya creativity, and served as another outlet for their spiritual and sociopolitical beliefs. They believed due to the pain involved during modification procedures, the person undergoing it went through a spiritual transformation as well as a physical one. Modification rituals were seen as the most effective way to communicate with their deities, and served the mutually symbiotic relationship they had with the Gods – you give us food, rain and life, and we will bleed for you in exchange.

Cranial modification of Maya male. Photo © Colette Dowell.

As seen with their near-vertical temples built into the skies, the Maya equated height with proximity to the Gods. Cranial manipulation was one of their most notorious and beloved practices. Boards were strapped to the front and back of an infant’s head to achieve a permanently elongated skull. Among 1,600 skulls acquired from 122 Maya cities during a study led by archaeologist Stephen Houston, 90 percent of them had cranial elongation. Resin beads were also hung from the hair on a child’s forehead to make them cross-eyed. They likened crossed eyes to the glare of a jaguar before it attacks its prey.

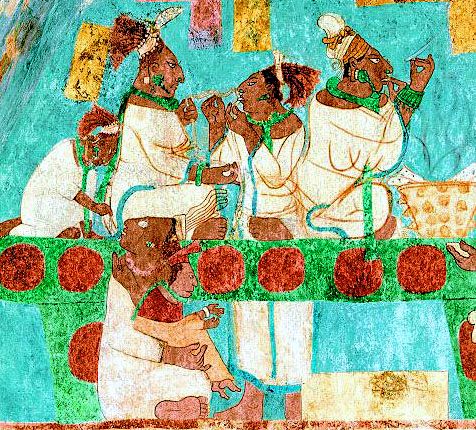

Mayan women perform bloodletting in an offering ritual.

They were known for dental modification, frequently embedding small pieces of jade, turquoise, obsidian and pyrite into their teeth. The Maya elite preferred to file their incisors into a T-shape. Mystery surrounds their seemingly expert medical application of stones. In a time of no documented dental hygienic practice, the holes and filings were done with such precision that rarely is serious damage or harm visible. There is little evidence of calcium deposits around the stones, and therefore little evidence that implants led to root damage or disuse of a tooth.

Stela 24 at Paxchilan, depicting Lady Xoc drawing a barbed rope through her tongue.

Royal bloodletting rituals were a vital part of Mayan life, as they believed the soul resides in the blood, and thus royal blood was revered as the most potent for offering to deities. Men practiced penile bloodletting, where they used a stingray spine to pierce the genitals, letting blood drip onto a piece of parchment which was then burnt as an offering. Some have suggested penile blood letting was done to compensate for women’s menstrual cycles. Elite men and women would pierce their tongues with a stingray spine, then a thorn-freckled or obsidian-embedded vine was inserted into the tongue and pulled through. These rituals drew large crowds to central plazas to witness and celebrate, as smoke rose towards the heavens from the bloodied parchment, with the hopes the offerings appeased the Gods. Satisfied Gods meant steady rains and a good farming season were on the horizon.

Lord K’inich Janaab’ Pakal seen wearing jade ear spools on this base relief at Palenque.

Tattoos were achieved by creating small ornate cuts on the skin and rubbing the wounds with pigment. Ear lobes, septum, nostrils and labrets were commonly pierced and stretched. Cords were run through the piercing and heavy stones were attached, weighing down and eventually gauging the piercing. When there was an elite bloodletting ritual, it was not uncommon for massive “piercing parties” to break out in the plaza, usually during a major astrological event. Body modification was not just encouraged, it was expected of all people. Bishop Diego de Landa, the famed Spanish destroyer of 95% of recorded sacred Mayan text, noted a dispute between two men in his book Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, in which one man exiled his son-in-law from the household for not having enough body modifications.