Several weeks ago, when I wrote this piece for CVLT Nation, my aim was to make people aware of something hugely important happening in a part of the world that the press won’t touch. Understandably worried that they’ll end up in the next ISIS beheading video, news agencies don’t have people on the ground in Rojava, embedded amongst not the people fighting for their freedom, but those living it day to day.

The original article got a lot of comments. Probably as many as if I’d written the article ‘Liturgy: Greatest Band Ever or Just Greatest Metal Band Ever?’. Most pointed out, quite correctly, that I was leaving out the subtleties of the conflict in Syria and post-state politics in general (which I reduced to the term ‘anarchism,’ though there are a lot of ways that what is happening in Rojava isn’t anarchist). The huge range of ideas that can be called ‘anarchist,’ even broadly, create the same problem that always comes up when discussing metal. So many contrary ideas are contained within these two words that every time they are invoked, everything inevitably devolves into a replay of the most incisive thing ever written about revolutionary politics: this Monty Python bit.

So, I’d like to focus in on the ideology that is behind Rojavae, while expanding to take in the ways in which libertarian socialism, democratic confederalism, Communalism, libertarian municipalism – whatever you want to call it – is being practiced. As you can see, even when zooming in from anarchism in general to one particular strain, there are still too many strands to ever really keep it straight.

© zoriah

© zoriah

Tying these threads together is the work of Murray Bookchin, whose work Abdullah Ocalan, the intellectual forefather of much that is happening in Syria at the moment, discovered in prison. Bookchin had a complicated relationship with major strains of anti-establishment thought, such as Communism, Anarchism and Libertarianism, having supported and rejected all at different times in his lengthy career. His rejection of ‘lifestyle anarchists’ for their superficial commitment to the ideology will probably be familiar to anybody who has ever seen the comment thread under a Deafheaven review – ‘hipster metal’ anyone?

The system Bookchin arrived at was named Communalism. Developing the idea of Libertarianism Municipalism that he first advanced in the 1970s, Bookchin envisioned a way of organizing society along the lines of small municipalities – towns, villages and village-sized parts of large cities. Each would take care of its own business, coming together to decide on matters that affect more than one municipality. These regional democracies can combine to form much larger confederations; private property would become the collectively-owned property of the municipality, but personal property would still be permitted – in practice, this means that a business you own may be turned towards the good of the people around you, rather than for your own personal enrichment, but it doesn’t mean that anybody’s going to take your television.

Although he was often accused of utopianism, Bookchin based his ideals on real world examples stretching back thousands of years. Citizens’ assemblies of the kind he advocated have existed since ancient Greece, have appeared in medieval Italy, Germany and Iceland, early twentieth century Ukraine, and numerous times in Paris during the multiple revolutions there that were brutally put down. The committees and councils of the American Revolution did far more to establish the republic than the deified, slave-owning ‘founders’ did. Most recently, and most like the current situation in Rojava, the Spanish revolution saw millions of people directly administer their own lives while surrounded by totalitarian thugs.

Unlike the left-anarchists that Bookchin disparaged as ‘lifestylers,’ he didn’t reject legal means of bringing this kind of society about. Rather than wait for a revolution to arrive, Communalists see opportunities to begin the transition right now by forming community organizations, housing co-ops and cooperative businesses that provide a better alternative to the state and capital, gradually making them obsolete. Right now, stateists can easily fall back on the argument over who will supply roads, schools, hospitals and the like when the state is gone – Communalists aim to provide an answer.

This doesn’t mean that everybody who has put ideas like Bookchin’s into practice has avoided armed struggle. The Zapatista Army of National Liberation, who I mentioned briefly in my last article, are much smaller than their Rojavan comrades, but have been active and established for much longer. Since 1994, they have been at war with the Mexican government, though for much of their existence they have been in a state of ceasefire. Their early military offensives were swiftly put down, but after their defeat they came into their own, implementing a system of autonomous villages similar to those in Rojava, with the same emphasis on ecology, women’s rights and indigenous identity. They are also the product of a Marxist-Leninist ‘revolutionary cell’ adopting radically new tactics. Gone was the insistence on a ‘revolutionary vanguard’ to impose the revolution onto the people from above. Their ‘leader,’ Sub-commandant Marcos, didn’t mince words here: ‘I shit on all revolutionary vanguards.’ Their media savvy, sense of humour and early adoption of the Internet has meant that despite their small size they are one of the most visible revolutionary groups on the planet.

© zoriah

© zoriah

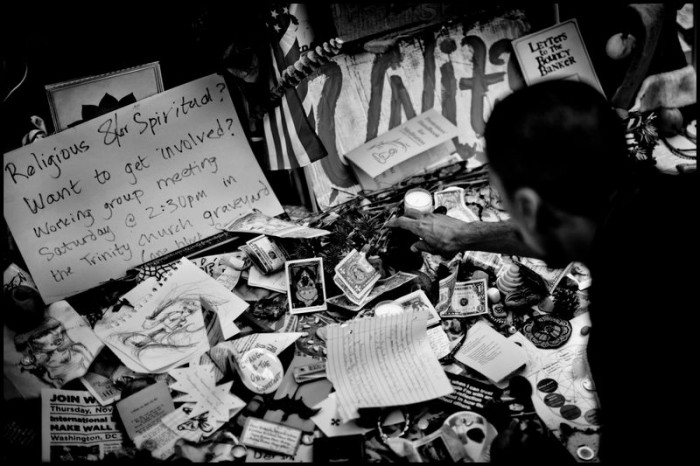

Even more visible – in the English-speaking world at least – was the Occupy Movement. Again, the movement lacked central leadership, with decisions being made by consensus in working groups and a central assembly. Almost from the start, Occupy was faulted for not having a goal, a set of demands, as if the Occupiers were going to do a SMART analysis on a whiteboard. It’s possible to see Occupy another way – as the 21st century, Western (or, in the many non-Western countries where it took off, Western-influenced) expression of the same ideals that motivate the Rojavans and Zapatistas. It was impermanent, heavily enmeshed in the virtual world, almost completely non-violent. Creating something, even temporarily, in the heart of places that belong to one’s ideological opponents, where you can’t be ignored, where your mere presence is an invitation to be tear-gassed, but which allows for marginal voices to be heard – that was the objective. It was a beta-test for a long-term occupation, a permanent community that has yet to arrive, and may need multiple successive trial runs before it can go live.

The point isn’t one that you’ll find often: there is actually cause for hope in this world, and I think that’s the reason so many people were attracted to my original article about democratic confederalism. Rojava may end in slaughter, the Zapatistas may fade into obscurity and Occupy may never surface again – but they happened, and they work. When they end, it’s rarely because of internal failure, but because of external violence; because, unfortunately, there is still a significant part of humanity that just doesn’t feel inspired to act by the possibility of a rational, peaceful existence. They’re fighting a losing battle. This system only has to work once over a large area with international visibility for all the arguments for the state to be rendered null.

References and Further Reading

Murray Bookchin, The Next Revolution: Popular Assemblies and the Promise of Direct Democracy (read the introduction by Ursula K. Le Guin here)

David Graeber, The Democracy Project: A History, a Crisis, a Movement

Leandro Vergara-Camus, Land and Freedom: The MST, the Zapatistas and Peasant Alternatives to Neoliberalism

Tom Hayden (Editor), The Zapatista Reader