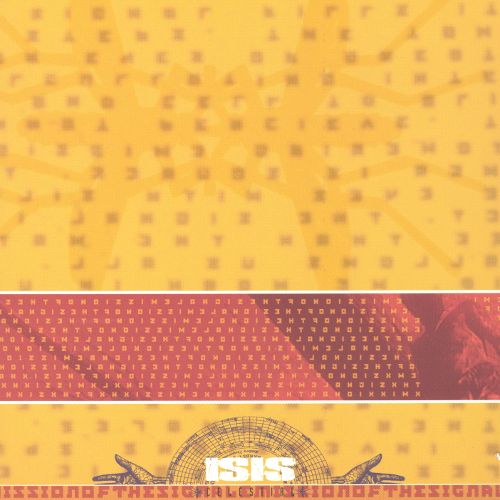

In the early 2000s, experimental heavy music was experimenting with dense, cerebral material and creating music with wild ambition. With their peers in Neurosis, Isis helped to pioneer post-metal, bringing a whole new palette and approach to extreme music. And now with Isis reforming – albeit briefly – under the Celestial moniker, it seems an especially good time to go back and rediscover their incredible debut record, some eighteen years after its initial release.

For many the reunion show was a little bittersweet: the tracks remain wonderful but the band who performed were older, more grizzled and the performance, a benefit for Caleb Scofield’s family, was tinged with sadness. In addition the band have arguably done their best work in the years since the split; Aaron Turner in particular helms the formidable Sumac, clearly built on the foundation of the more feral Isis outings (not to mention Old Man Gloom), but Jeff Caxide, Aaron Harris and Bryant Clifford Meyer went on to form Palms, an expansion on (and a poppier reaction to) the floater post-metal established on Oceanic and Panopticon.

Celestial, the culmination of the sound cultivated on their debut EPs Mosquito Control, The Red Sea and Sawblade, pushed them into more challenging territory. Embracing a more thematic approach, the album references the Mother/Tower themes, referencing technology and the erosion of personal liberty (later probed further on Panopticon).

Musically, the record is monstrously heavy. Starting with a curious industrial/insectoid scratching (SGNL>01), the record bursts into “Celestial (The Tower),” a chuggy track peppered with sparks of noise. The central riff cycles through variations before reaching its culmination with a sweeping electronic section, awash with spacey noises, like a washed-out Hawkwind. “Glisten” kicks things back op after the lull, and from there the light/ dark pattern is established as a framework to house the harsh guitars and ambient electronics. This takes myriad forms, introducing new ideas and jerking them away, squeezing a riff until it changes, building songs up only to have the guitars drop away so the underlying hard ambience is all that remains.

“Deconstructing Towers,” the most ferocious outing on the record, is harrowing, the flirtation with feedback and noise coming to be fully embraced. Here the careful architecture of the record is contrasted with uncontrollable bursts of wailing, structureless anti-music. It’s the gem of a varied, focussed record, and subsequent tracks don’t attempt anything as destructive. The last half of the record is generally more subdued, the final two SGNL tracks completing their first cycle and “New Circuitry” and “Continued Evolution” adding a gentler tone. The record ends with “SGNL>04,” a more subdued take on the scratchy examples found earlier.

As a bonus, some of these themes are expanded on the EP SGNL05, which expands on the scratchy space noises but adds elements of free jazz and, though it features some more traditional heavy moments (particularly “Divine Mother”), leans more into the more formless, experimental elements as displayed on the record. The closing track “Celestial (Signal Fills the Void)” is a companion piece to “Celestial (The Tower),” and the tracks have been performed in tandem live. The track – and this cycle of Isis – ends with, well, celestial-sounding synths in the Jesu tradition, a fitting conclusion.

It’s odd that Celestial so clearly references Godflesh when Turner later went on to collaborate with Justin Broadrick on the mortifying Greymachine (and as cover artist for several Jesu releases, not to mention his involvement with Hydra Head). Indeed, there are plenty of bands which contribute to the rich aural background of the record; certainly Black Sabbath (who they later covered) and Pink Floyd’s wilder experimentations (much more apparent on Oceanic/ Panopticon). The record is clearly in-line with some of the Neurosis material which had emerged by that point, but Celestial showed they clearly emerged with their own personality for two bands with a similar aesthetic and ambition.

Listening back, the record is still as feral as when it was recorded, still as steeped in oblique mystery (which makes it a little arrogant), still a record that forces the listener to engage with frosty harsh noise alongside weighty, satisfying riffs, little of which is welcoming or accessible. Of all of the post-Isis material, Turner’s work with Sumac is closest to its unhinged energy, anger and ferocity, but also the creative spirit in which it achieves these goals. To expand on this, this was the framework for so much that came after it; who hasn’t picked up a post-metal record and heard a segment that could be lifted straight from Celestial?

It’s never a bad time to revisit the record, and for those who have taken Caleb’s loss hard, it’s a good time to look to one of the key early moments in the scene in which he was a key player. Celestial was the birth for so much, and despite its oblique themes remains a joyous record.