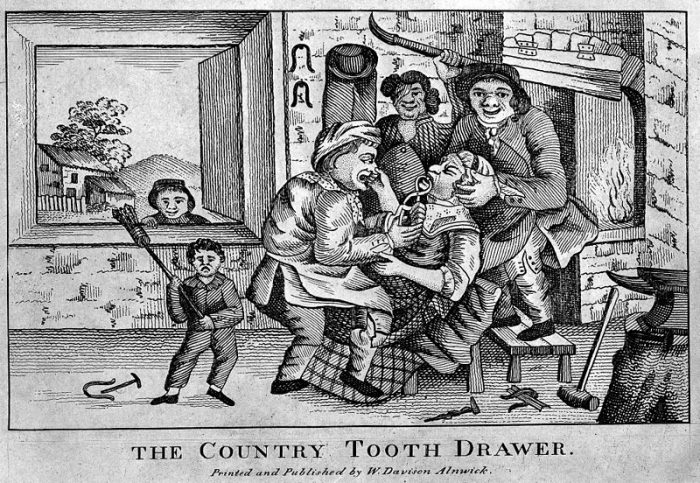

If you are anything like myself, a trip to the dentist is cringe-worthy at best, and utterly terrifying at worst. I had a colleague of mine, a dentistry student, describe this as “irrational, but not uncommon.” Though it is perhaps of little comfort, visits to the dentist, or the “tooth drawer,” as some practitioners who specialised in –you guessed it – pulling out teeth were called, were a little bit riskier in the past. The profession and science are relatively new, even accounting for the development of medical science as we know it, with the eighteenth-century dentist Pierre Fauchard, often referred to modern dentistry’s “father,” writing a scientific treatise on dentistry, Le Chirurgien Dentiste, describing oral anatomy, basic practices, oral pathology, amongst other things.

“The Country Tooth Drawer”, Courtesy of Wellcome Images

Before standards of practice, professional accreditation, education, and organisations were formed during the nineteenth-century, basic dental services were commonly provided by barbers (of the “barber-surgeon” variety, who did, also, offer shaves and haircuts) or tooth-drawers. Blacksmiths sometimes dabbled in dentistry as well, offering extraction services for a fee. This could be risky business, as this was prior to a good understanding of hygiene, disinfection, and oral anatomy. Some common themes in Northern Baroque genre paintings were market scenes with charlatan dentists on a platform flanked by an ape, ready to pull the teeth of a frightened customer. In fact, some of these procedures were charades to attract clients, with an accomplice planted in the audience, later given a fake, bloody tooth by which the tooth drawer could proclaim success without having pulled any teeth. Those who were convinced by the act were in for something entirely different.

Pietro Longhi “The Tooth Puller”, 1746

Theodoor Romouts “The Dentist”ca 1620-5 – look closely at the dentist’s necklace.

Others depicted dentists decorated with extracted teeth. Graced with necklaces and wide-brimmed hats with hanging teeth on display, the amount of fully drawn teeth – root and all – was an indication of the tooth-drawer’s skill, as a broken tooth could very likely cause infection and kill the suffering client. Even if the tooth had been fully extracted, a piece of bone could have tagged along, leaving the tooth ache sufferer with a broken jaw and deformity if given the chance to heal without further complication. And, maybe art did imitate life. Much to the chagrin of his peers in the early twentieth century, American dentist Edgar “Painless” Parker pulled 357 teeth in one day, strung them, and wore them as a necklace, much like the fellow in the above painting by Theodoor Romouts.

Further reading:

“Painless Parker: Part dentist, part showman, all American”, BBC: Magazine, 11 May 2015. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-31704287

Karl A.E. Enenkel, “Pain as Persuasion: The Petrarch Master Interpreting Petrarch’s De remediis“, in The Sense of Suffering: Constructions of Physical Pain in Early Modern Culture, eds. Jan Frans van Dijkhuizen and Karl A.E. Enenkel: 91-165.

Matt Filder, “A History of Dentistry in Pictures”, The Guardian, 16 June 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/society/gallery/2014/jun/16/a-history-of-dentistry-in-pictures