In part one of this examination, we looked at how the French Revolution upended traditional seats of authority in France. The Monarchy was literally decapitated, and the Church’s role in French society was greatly diminished. In the wake of the French Revolution – and the Enlightenment that helped spawn it – Romantic writers and artists adopted Satan as the conquering hero, who unseated absolutist authority with a rebellion that was based upon individual sovereignty and reason. While these authors were not actual practicing Satanists, they did tap into a current of thought that was running through post-revolutionary French society – and there were those that took the newfound image of the Devil as a liberating archetype more deeply to heart.

In part one of this examination, we looked at how the French Revolution upended traditional seats of authority in France. The Monarchy was literally decapitated, and the Church’s role in French society was greatly diminished. In the wake of the French Revolution – and the Enlightenment that helped spawn it – Romantic writers and artists adopted Satan as the conquering hero, who unseated absolutist authority with a rebellion that was based upon individual sovereignty and reason. While these authors were not actual practicing Satanists, they did tap into a current of thought that was running through post-revolutionary French society – and there were those that took the newfound image of the Devil as a liberating archetype more deeply to heart.

With the demise of the Church, individuals around France began looking elsewhere for answers to life’s great mysteries, or at least found themselves emboldened enough to challenge Church orthodoxy. Along with the already established Freemasons arose a hodgepodge of upstart secret societies, as well as the increasingly popular Spiritualist movement. Certainly the most important figure to emerge from the mystical stew of 18th Century France was Occultist Eliphas Levi. To understand Levi’s brand of occultism, one needs to understand that like many French occultists, his ideas and identity were drawn in the shadow of the Catholic Church. Studying to become a priest, Levi fell in love and left the seminary to marry, but he never fully abandoned his Catholic beliefs. Turning his concerns to the state of post-revolutionary France, Levi initially became a voice for radical socialism based upon Catholic universalism.

After repeatedly being disappointed and revising his approach to social and economic change, Levi became immersed in magic and the occult. Still not abandoning his Christian orientation, he turned to Tarot and Jewish Kabbalah as means by which to uncover the universal truth of God. Levi laid out his “all is one” universalist approach to the occult in a number of books, the most important and influential being Dogma et Ritual de la Haute Magie, or Transcendental Magic, its Doctrine and Ritual, in 1856. In that work, Levi states that all ancient mystery practices, initiations, ceremonies and writings were “indications of a doctrine which is everywhere the same and everywhere carefully concealed.” As if to literally illustrate this very point, Levi produced arguably the most profound image in the history of the occult – Baphomet.

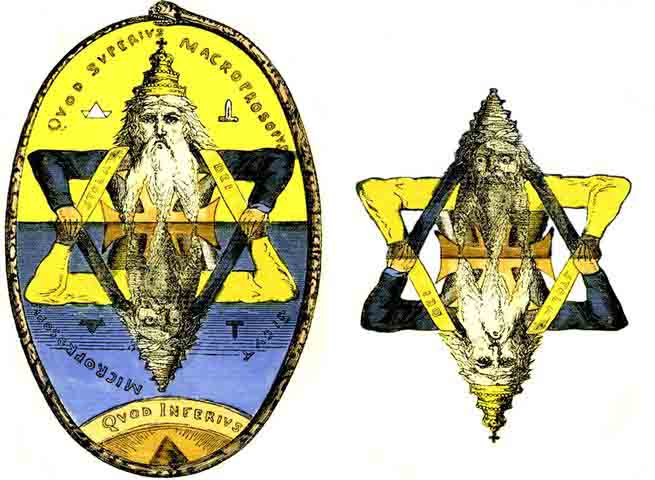

His Goat of Mendes, or Sabbatic Goat was a visual manifestation of the unification of opposites and elements of the universe to represent the “Universal Agent,” which is less like the Christian God, and more akin to the great Tao. It is clear from this that Levi’s understanding of “God” was far transcending that of the Church’s, which informed his early life, and was instead something more natural, elemental and primal, but one that still extended throughout the universe, into the heavens and cosmos. For certainly this is made clear in another famous illustration by Levi in Transcendental Magic; “The Great Symbol of Solomon,” which illustrates the occult maxim “As Above, So Below.” Levi’s whole understanding of the “Universal Agent,” or Truth, is the synthesis of light and dark, male and female, creation and destruction. Each is a manifestation of this Truth and each a pathway to this Truth.

Inherent in all of Levi’s work and illustrations is the implication that things are not as they initially seem. In Baphomet, one sees first and foremost the terror of the Christian Devil, but Levi asks us to look deeper. In doing so, we uncover the god of the great Witches’ Sabbat, the Great God Pan (whose name literally means Universal). This god, Levi notes, is “the god of our modern schools of philosophy, the god of the Alexandrian theurgic school and of our own mystical Neoplatonists, the god of Lamartine and Victor Cousin, the god of Spinoza and Plato, the god of the primitive Gnostic schools; the Christ also of the dissident priesthood.” Therefore, the Devil, or the “Old Serpent,” is really just an aspect of the Universal Agent. The effect this idea has had on the occult, gnosticism and theistic Satanism is immeasurable.

Lest one think that Levi was a Satanist, though, one need only turn to his opinion of black magic. While Levi thought the Devil represented the “eternal fire of terrestrial life, the soul of the earth,” and a force that in itself was neutral and able to be tapped for good, it could also be used for black magic, which he roundly condemned. Much like Augustine, who viewed sin as an irrational disorder in a rationally ordered neoplatonic universe, Levi emphasized, “in black magic, the Devil is the great magical agent employed for evil purposes by a perverse will.” He acknowledged its use and power, but vilified its use as a disorder, akin to insanity (keeping in mind that in a properly ordered neoplatonic universe reason and rationality are what is “good,” while insanity is the disordered corruption of that good).

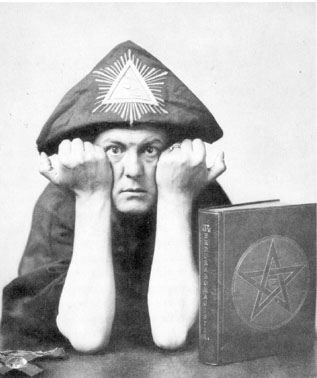

Another of Levi’s magical concepts that had a profound impact on Satanism, and modern Luciferianism, was “The Great Work.” This was described by Levi as “the creation of man by himself, that is to say, the full and entire conquest of his facilities and his future; it is especially the perfect emancipation of his will, assuring him….full power over the Universal Magical Agent.” The idea being that mastery of magic is mastery of the will and the universe itself through alignment of one’s will with the Universal Agent, thus gaining the ability to shape the world in accordance with one’s properly ordered Will. This, of course, is the basis as well for Aleister Crowley’s work, and is the idea behind his famous maxim, “Do What Thou Wilt.” In Crowley, like in Levi, there is a belief in a greater transcendental Universal Agent, and like Levi, despite any beliefs to the contrary, Crowley’s system of magick was in the service of accomplishing the “Great Work,” and not the work of a black magician.

Another of Levi’s magical concepts that had a profound impact on Satanism, and modern Luciferianism, was “The Great Work.” This was described by Levi as “the creation of man by himself, that is to say, the full and entire conquest of his facilities and his future; it is especially the perfect emancipation of his will, assuring him….full power over the Universal Magical Agent.” The idea being that mastery of magic is mastery of the will and the universe itself through alignment of one’s will with the Universal Agent, thus gaining the ability to shape the world in accordance with one’s properly ordered Will. This, of course, is the basis as well for Aleister Crowley’s work, and is the idea behind his famous maxim, “Do What Thou Wilt.” In Crowley, like in Levi, there is a belief in a greater transcendental Universal Agent, and like Levi, despite any beliefs to the contrary, Crowley’s system of magick was in the service of accomplishing the “Great Work,” and not the work of a black magician.

At the same time, this idea that the individual’s Will could be the basis for the creation of reality has been stripped to its very essence in modern Luciferianism, with or without a transcendental agent by which to unify with. Similarly, Levi’s mystification and sanctification of the Devil in his work opened the gates for transcendental Satanism, as did his discussion about aligning the will with the Devil, despite his condemnation of such activity. It is no coincidence that the Temple of Set subscribes to neoplatonism in the same manner that Levi and Crowley did.

So while Levi was not a Satanist, his work greatly informed modern Satanism, as well as that of the French occultists who practiced in his wake – some of who are alleged to have been given into the temptation of the power promised by black magic that Levi so vehemently warned against. In part three of this series we will turn to their supposed nefarious activities.