He was three times nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature, an accomplished bodybuilder, a trained soldier, an expert swordsman, a model, an actor, a singer. Any one of these achievements is impressive, two or three exceptional, all of them taken together is evidence of near superhuman willpower, an Übermensch towering above us ordinary mortals.

But then Yukio Mishima had a darker side: tormented in his youth by a disturbed grandmother with aristocratic pretensions, shamed by his overbearing father into hiding his early work, possibly closeted or bisexual, partly the model of Japan’s westernised post-war generation – and on a deeper level, a throwback to its imperial past. The guy was complicated.

Born in Tokyo in 1925, Kimitake Hiraoka (Yukio Mishima is a pen-name) was the child of upper middle-class parents, who a hundred years ago would have served feudal lords, but who now found themselves serving a unified, modern nation as government bureaucrats. Almost as soon as he was born, he was snatched away by his grandmother, Natsu, the granddaughter of a Daimyo (a powerful feudal lord) and wife of a wealthy government offical. Natsu was prone to outbursts of violence and melancholy, and enforced a strict regime on the infant Yukio’s life, only allowing his mother to see him at appointed times for timed breastfeeding sessions. The company of other boys, sports and even sunlight was off limits, so Yukio would spend his days playing with his female cousins’ dolls.

When he was older and his grandmother’s grip on his life loosened, it was replaced with his father’s overwhelming concern that Yukio wasn’t ‘masculine’ enough, and the prime evidence of this was his son’s writing (apparently Hiraoka senior had never heard of Hemingway, Mailer or any of the other literary tough-guys who combined a love for the written word with scotch and fistfights). Despite his father’s interference, Yukio was getting good, and soon his short stories were appearing in prestigious literary magazines. One early story, 1946’s ‘The Cigarette,’ describes the shame he felt and the bullying he endured when he ‘came out’ to his friends in his school’s Rugby club about his membership in the school’s literary society.

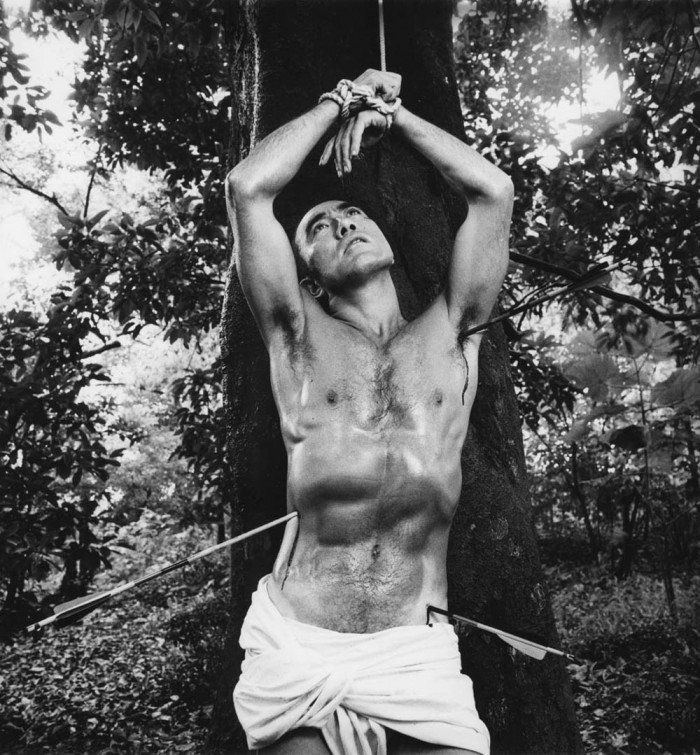

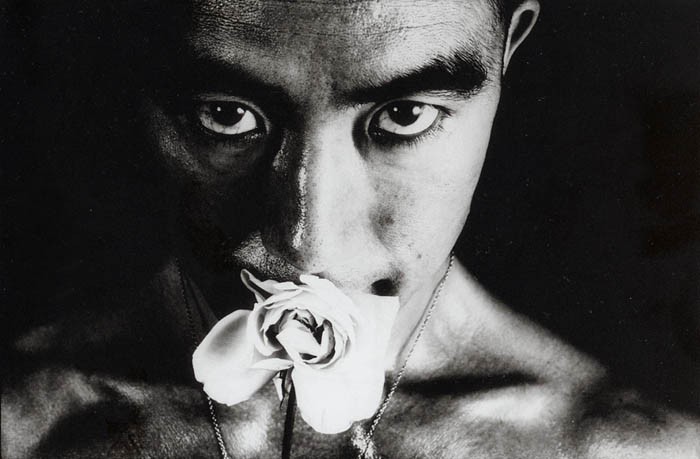

His first novel, 1949’s Confessions of a Mask, was an explosive hit upon its release. The novel was loosely autobiographical: it’s narrator, like Yukio, was a sickly child, small and physically frail, but a deep admirer of masculine strength and beauty. The narrator is also secretly gay, and in right-wing pre-war Japan, that’s practically a death sentence. Speculation about Yukio’s sexuality followed him throughout his life, and has never been satisfactorily answered: he was married and had children, but also frequented gay bars (perhaps for research into his often homosexual characters) and was often photographed in homoerotic poses, bare-chested and oiled, stripped down to a loincloth or as Saint Sebastian, an early Christian matyr shot through with arrows who has become something of a gay icon over the years (and maybe always was.) It’s definitely the case that he had a long-term affair with another award-winning writer, Jiro Fukushima, who first visited Yukio to ask where to find the gay bar described in his novel Forbidden Colors.

Over the next twenty years, Yukio would write 34 novels, 50 plays, 25 books of short stories, and at least 35 books of essays, all the while also posing for photographs, starring in films and living the life of his country’s foremost literary figure. His politics had always skewed to the right, but it was a conservatism rooted in his country’s past instead of a push towards a western-style future or the emulation of European fascism and nationalism that had driven his country to war. Bushido, the Samurai code of honor, figured prominently for him. For Yukio, embracing Bushido meant rejecting the industrialized militarism that had began in the Meiji period (1867) – to his critics he was a right wing loon, no better than those driving around Tokyo in speaker-equipped vans delivering sermons on lost honor and traditional values. The figure of the emperor also loomed large over his nationalistic thought, though he denounced Emperor Hirohito for, of all things, declaring that he wasn’t a demi-god after Japan’s defeat in World War II. In Japanese tradition, the emperors are descended from Amaterasu, goddess of the sun. Few, if any, Japanese citizens, including the emperor himself, really believed this, but for Yukio the statement was a betrayal of the men who had fought for a ‘living god.’ He declared that Hirohito should have abdicated when the war was lost, which enraged more mainstream right-wingers.

After years of seeing his right wing beliefs almost eclipse his literary achievements, Yukio decided to take action. He enlisted in the Ground Self Defense Force and underwent basic military training; then, a year later in 1968, formed a group that called itself the Tatenokai – the shield society. He recruited close to a hundred young men, mostly college students, and began training them in karate and military tactics (they were allowed to train alongside the Ground Self Defense Force). Ostensibly, they were a volunteer militia who would protect the emperor in the case of a left-wing revolt, but two years after they were formed, their true purpose became known.

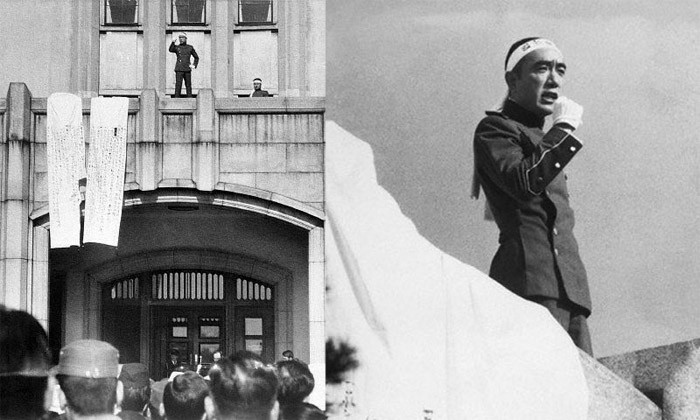

On November 25, 1970, Yukio and three members of the Tatenokai bluffed their way into the Tokyo headquarters of Japan’s self-defense forces. Once there, they took a high-ranking official hostage and barricaded themselves in an office. Wearing a homemade uniform, Yukio Mishima stepped out onto a balcony overlooking a field where soldiers were training and began to give a speech. This was his big moment – all his fame and achievement was nothing compared to what he was about to do on that balcony. He was going to change Japan, the world even, and restore the honour it had been losing since the ‘black ships’ of the first European traders arrived.

He was laughed off the balcony shortly after his speech had begun. Ashamed, he retreated back into the office and knelt on the floor, drawing his tanto – a short dagger.

Seppuku, often called ‘hari-kari’ in the west, is an excruciating way to die, even when done correctly. Though far too many western-made films depict it as a disgraced samurai simply impaling himself on his sword (and dying instantly), the correct way is to plunge the twenty-five centimeter long blade into one’s abdomen and begin cutting from right to left, with the aim of spilling one’s intestines. At a specified point another samurai, called the kaishakunin, will cut your head off – if they do it right, a sliver of flesh on the neck will remain so that the head can hang in front of the body.

The Tatenokai members accompanying Yukio didn’t exactly get his, or their own, seppuku right. Yukio did his part, cutting his stomach open, but his kaishakunin, Masakatsu Morita, failed to decapitate his leader after several attempts and passed his sword to another Tatenokai member, Hiroyasu Koga, who finished the job. Yukio would have been alive until the final blow. Morita stabbed himself in the stomach, and again, Koga, a skilled Kendo practitioner, stepped in to do his duty. It is rumoured that he now lives as a Shinto priest on the island of Shikoku.

It’s unclear whether his coup attempt was merely a pretext for a nobler suicide than he could have achieved at home with pills and vodka. It’s clear that the world lost a monumental talent: in the moments before his death, he composed a jisei, a death poem:

“A small night storm blows

Saying ‘falling is the essence of a flower’

Preceding those who hesitate”