In 1656, King Louis XIV ordered the La Salpêtrière gunpowder factory to be converted to a hospice for poor women. His idea was to round up all of the impoverished people in Paris, and house them out of the way where they couldn’t tarnish the reputation of the glamorous city. So, La Salpêtrière began its 400 year journey to the present, including being the hospital where Princess Diana was pronounced dead in 1997. The Journal of Rheumatology published a lengthy article about the hospital’s history (I’ve included excerpts below), and pointed out the irony of Diana — a pop culture Mother Mary — dying at a hospital that spent so many centuries as a home to the “female dregs of society.”

All images via Wellcome Collection (CC)

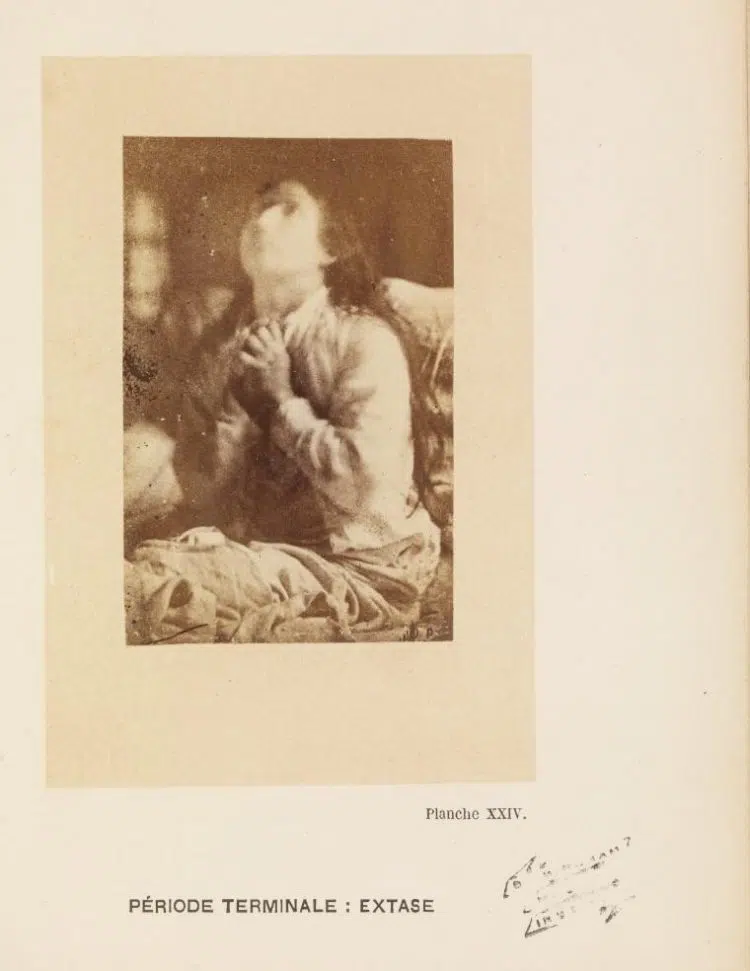

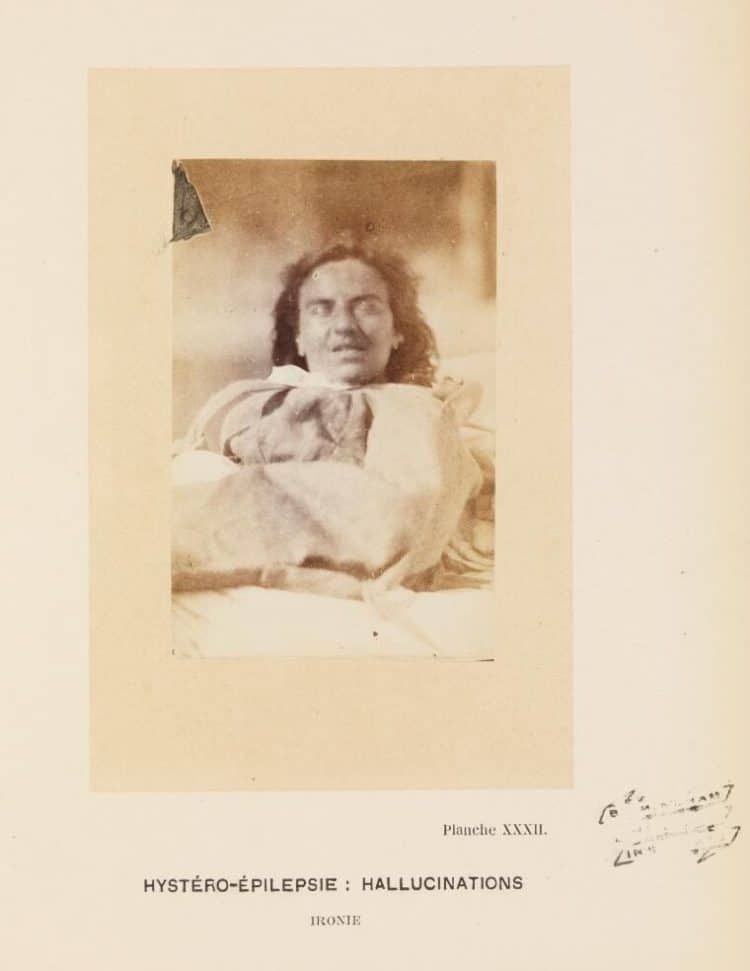

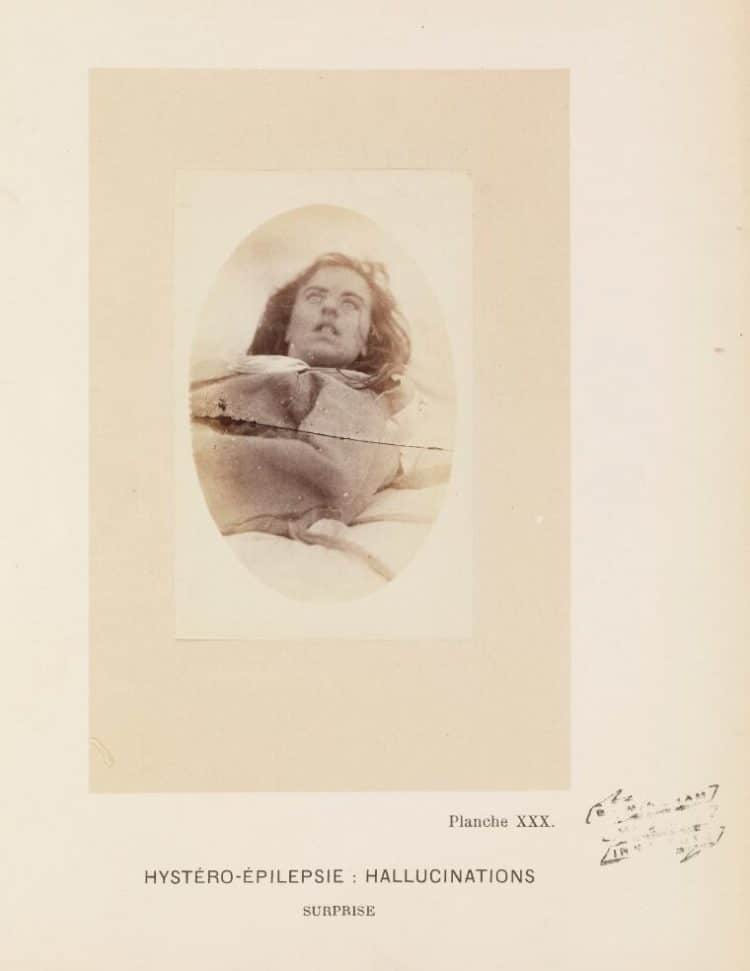

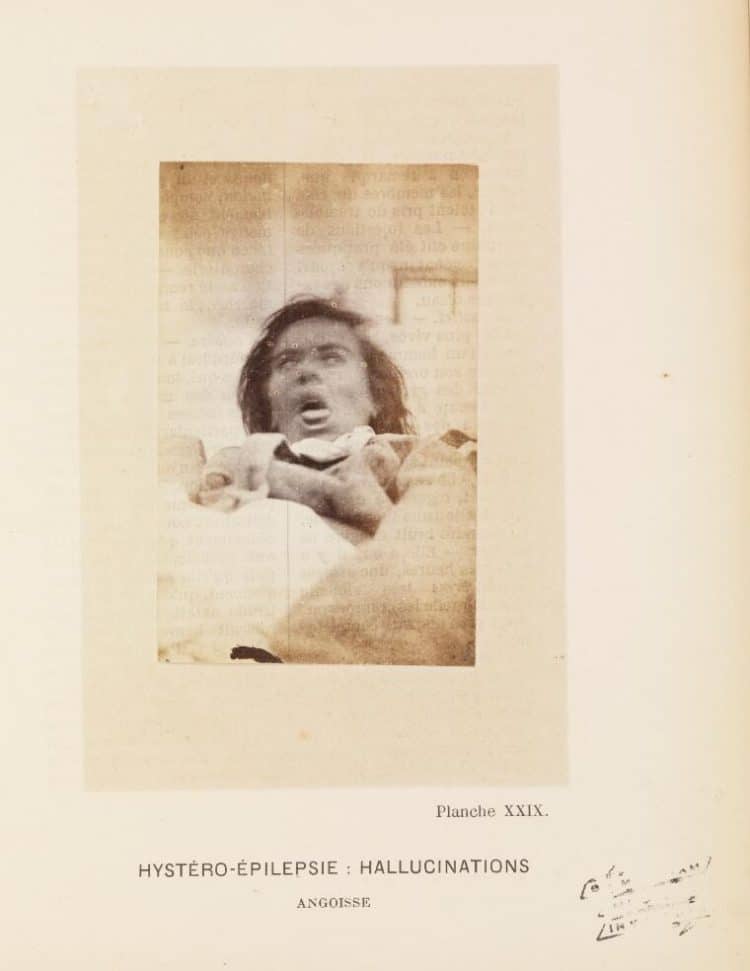

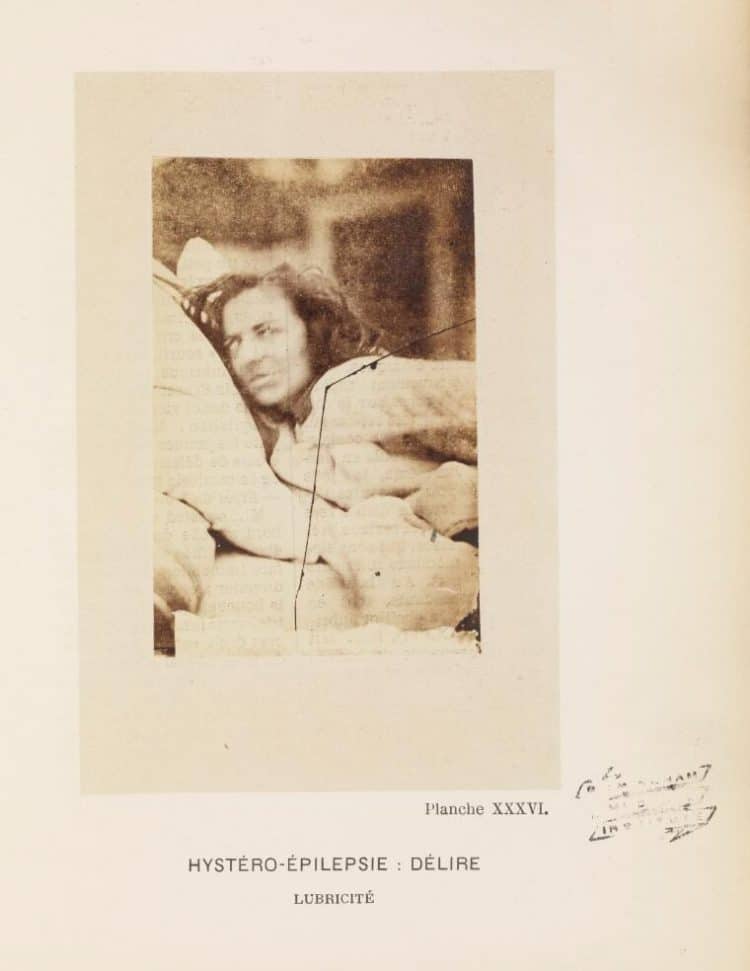

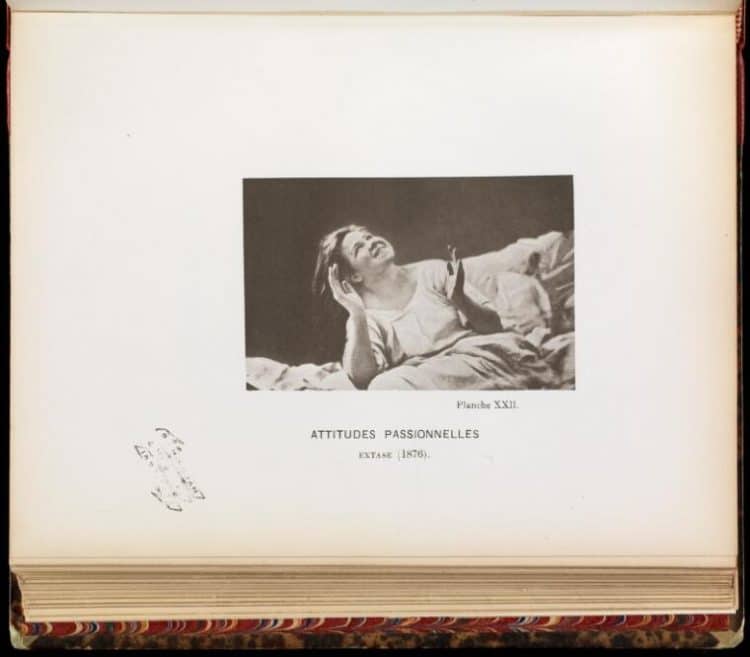

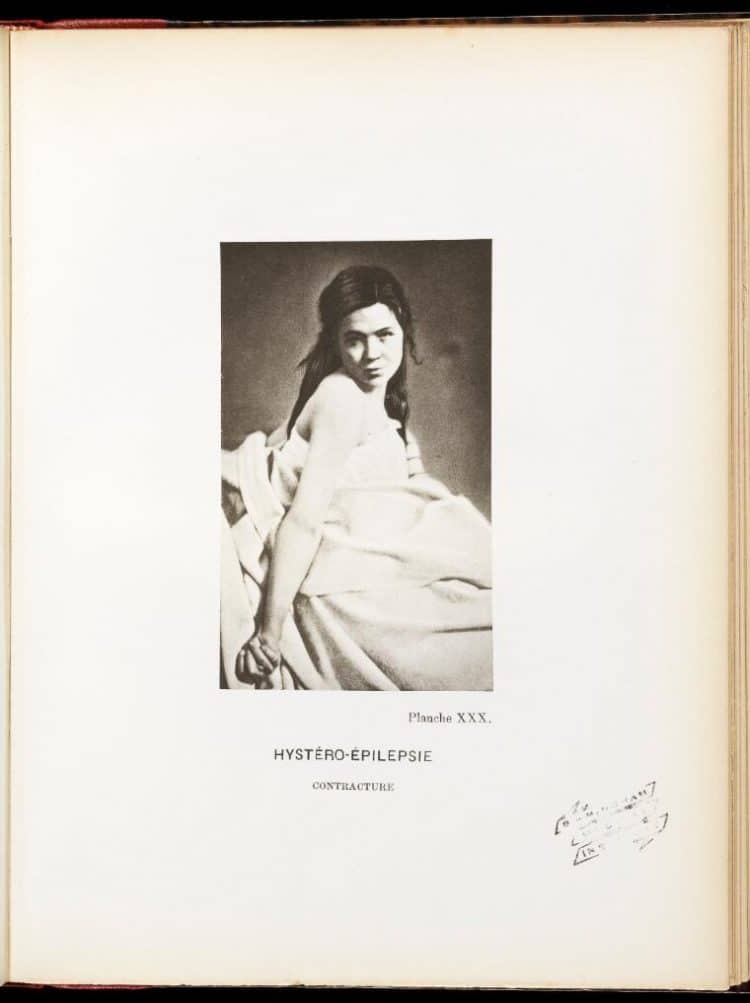

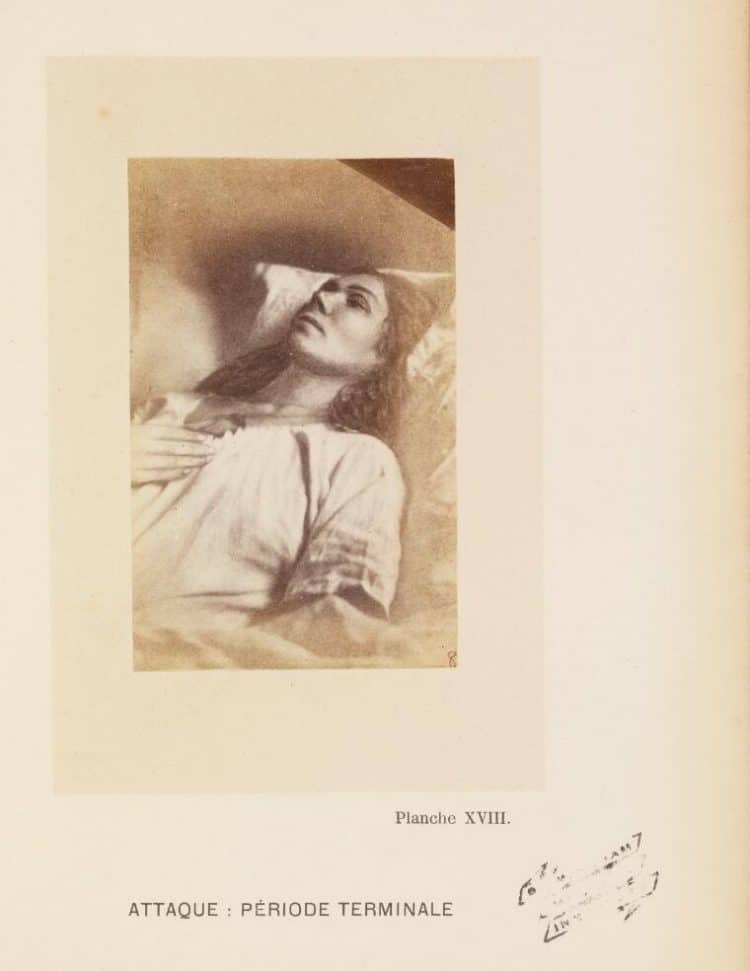

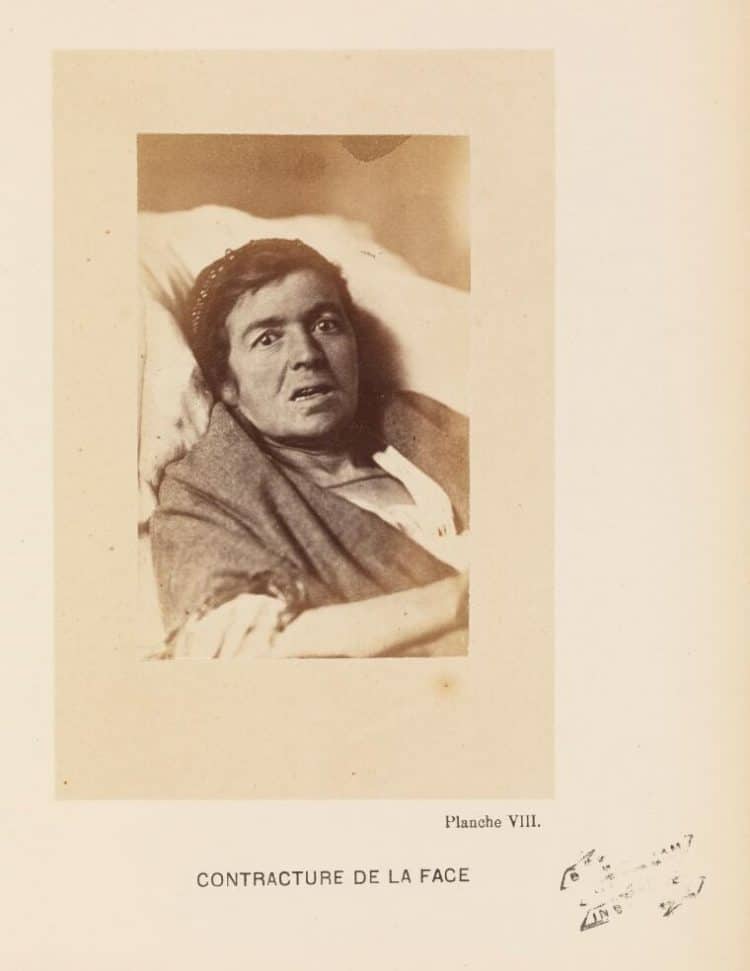

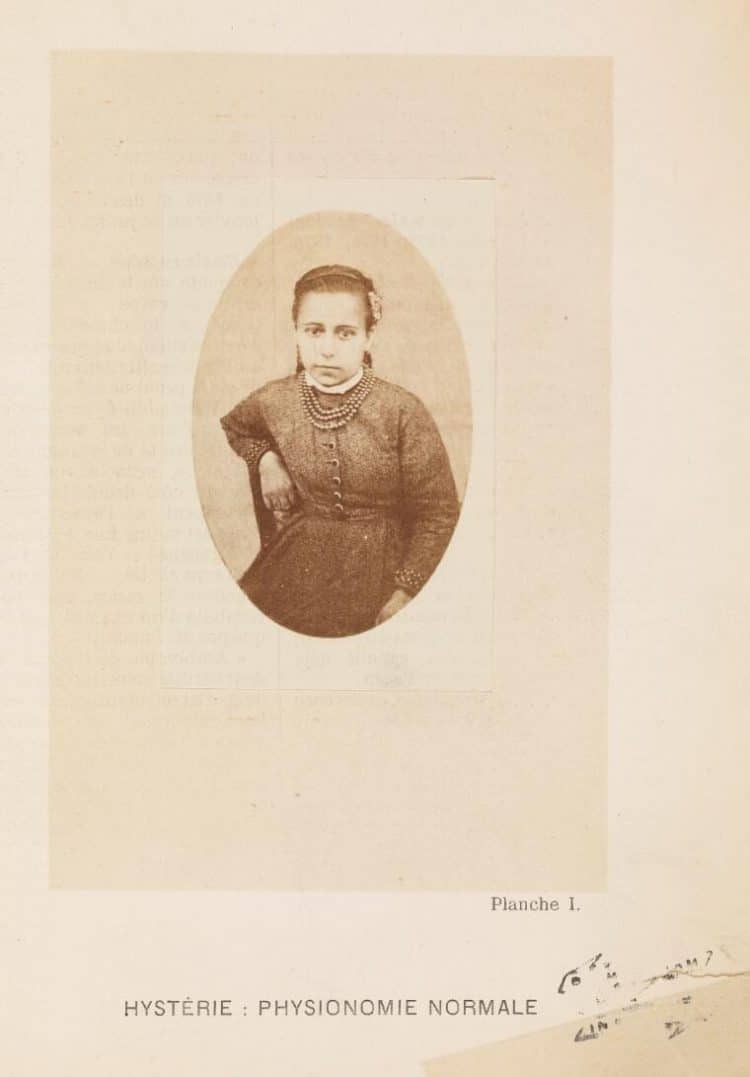

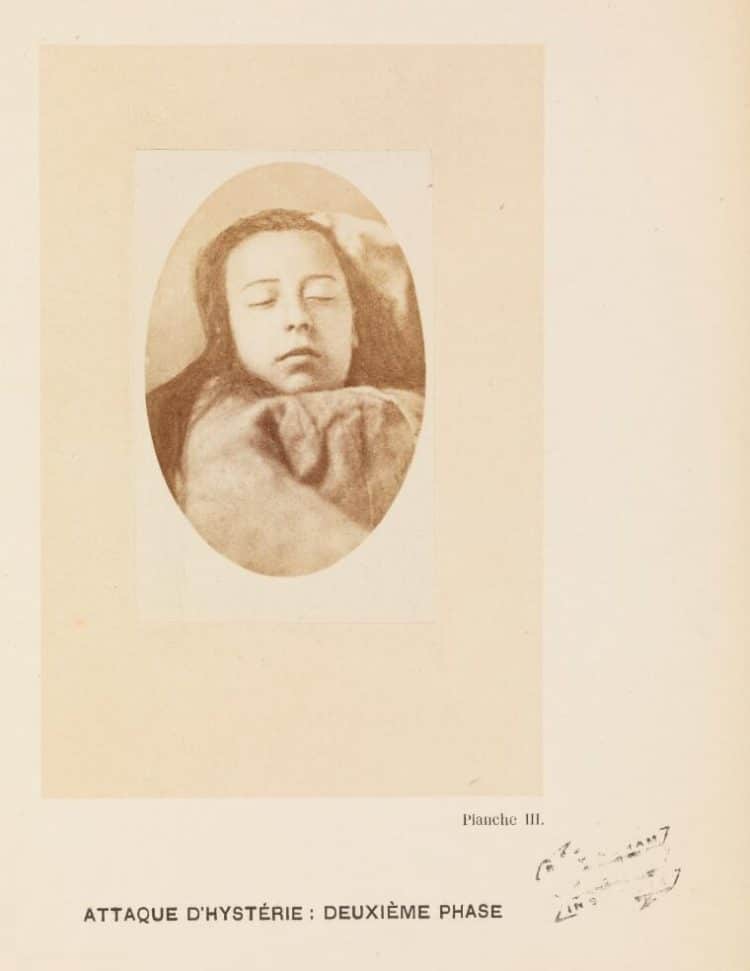

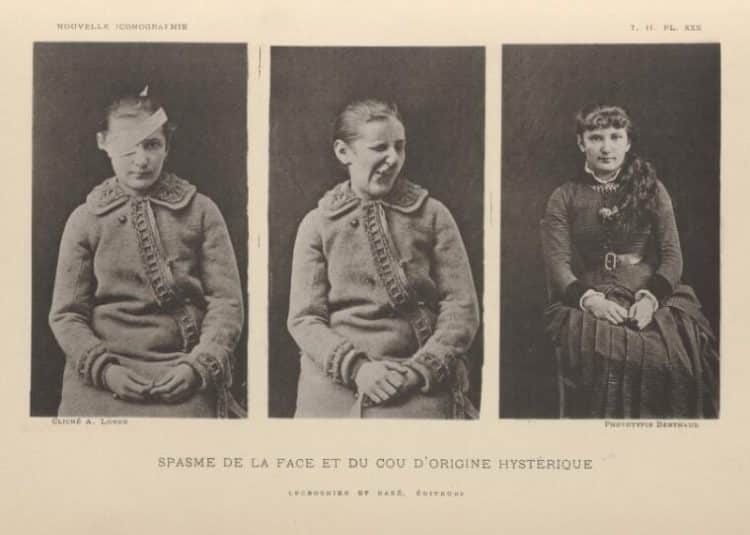

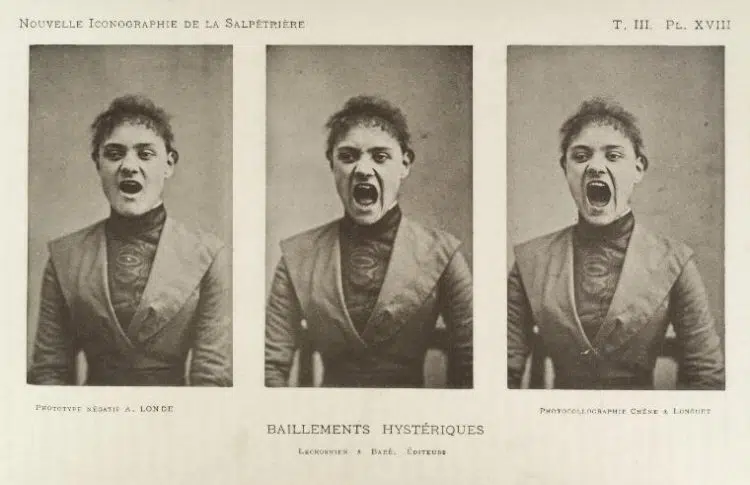

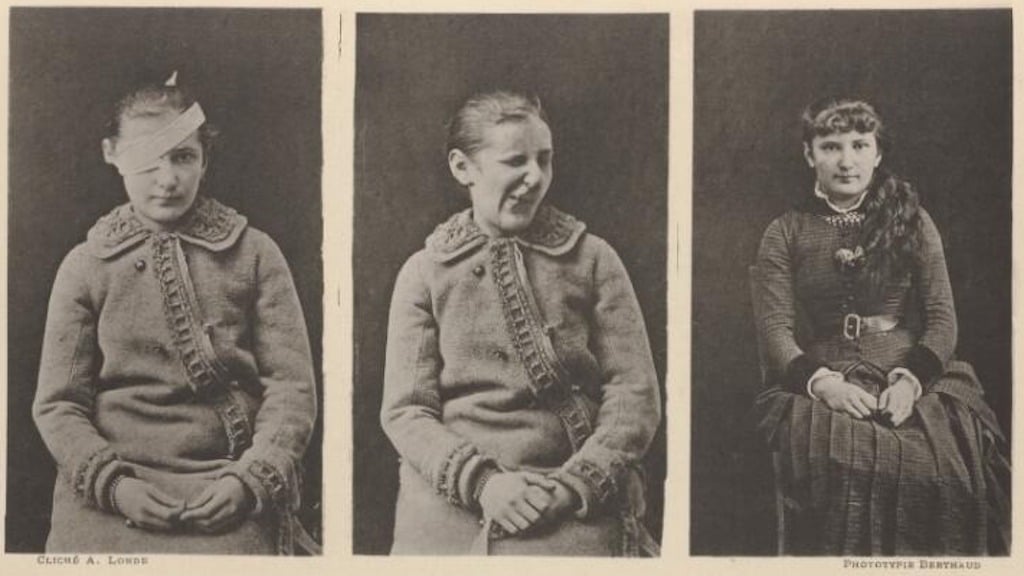

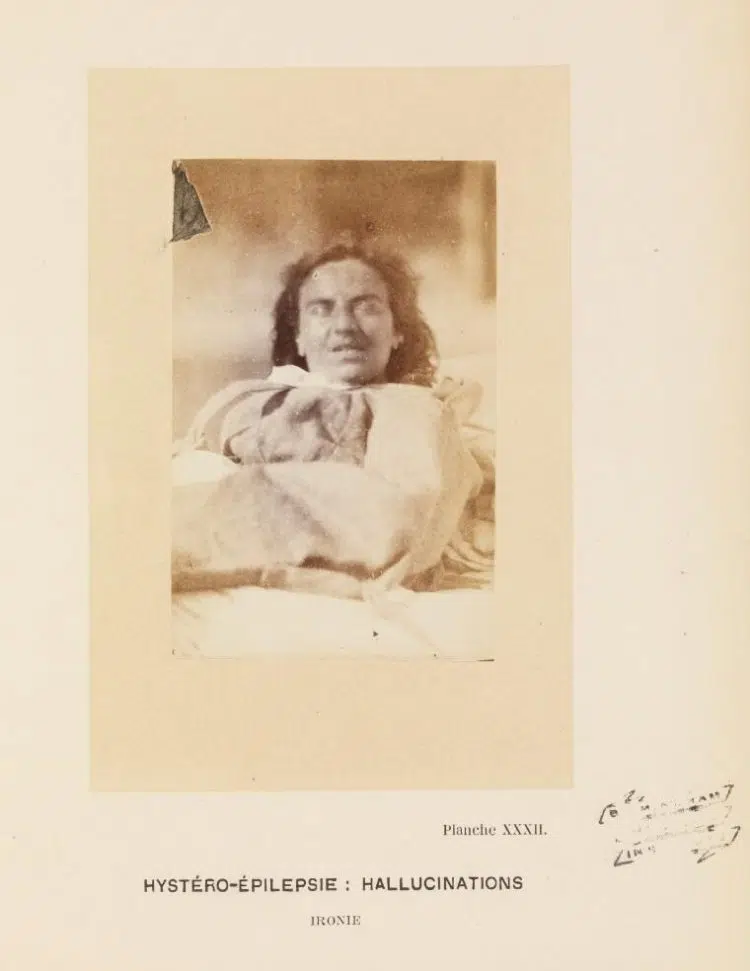

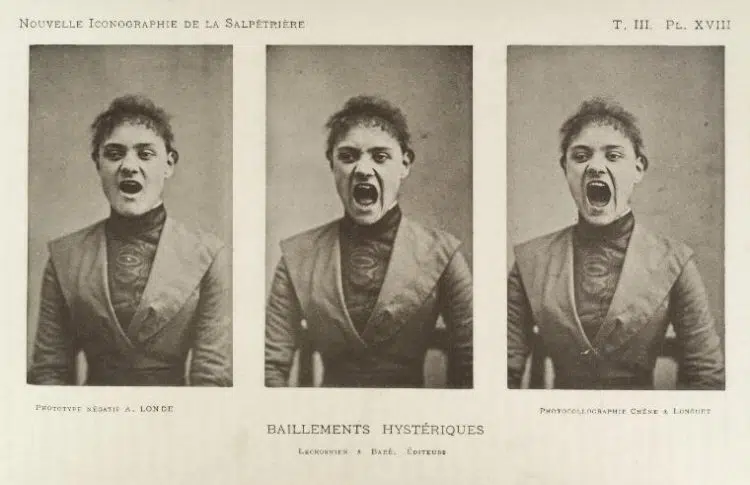

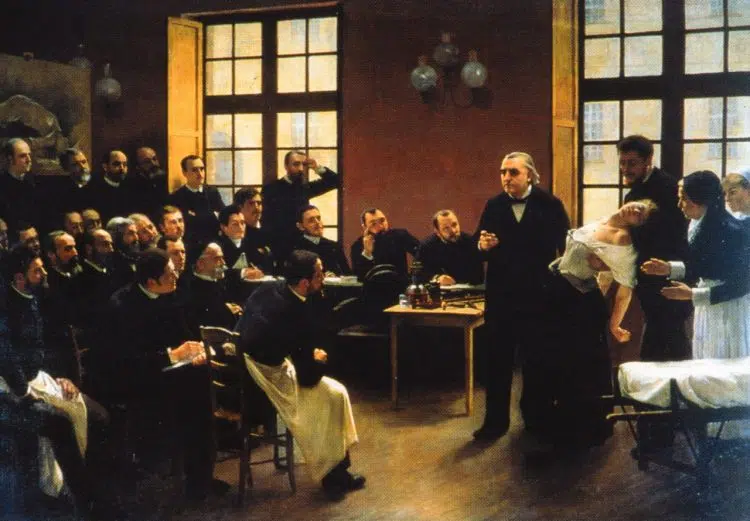

One of Western medicine’s most influential physicians, Jean-Martin Charcot, became known for his work on hysteria at La Salpêtrière. He studied the women housed there — many of whom were prostitutes, including some famous dancers from La Moulin Rouge — and he would have them put on live demonstrations of hysteria for his esteemed male colleagues. Amongst Paris’s prostitutes, Dr. Charcot’s hysteria demonstrations were well known, and even aspired to.

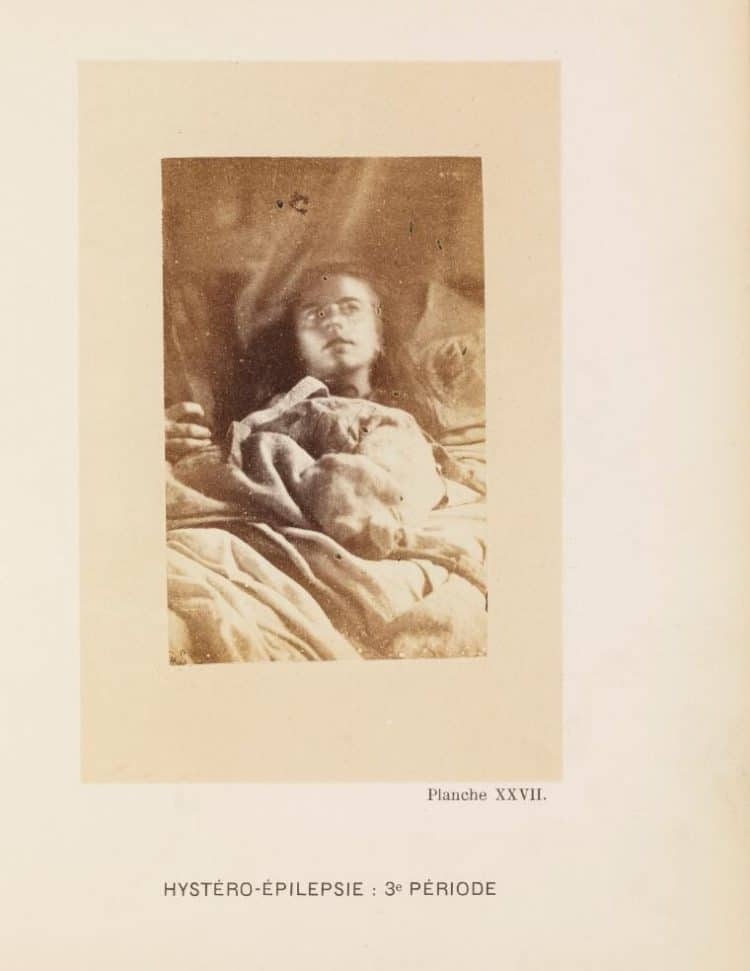

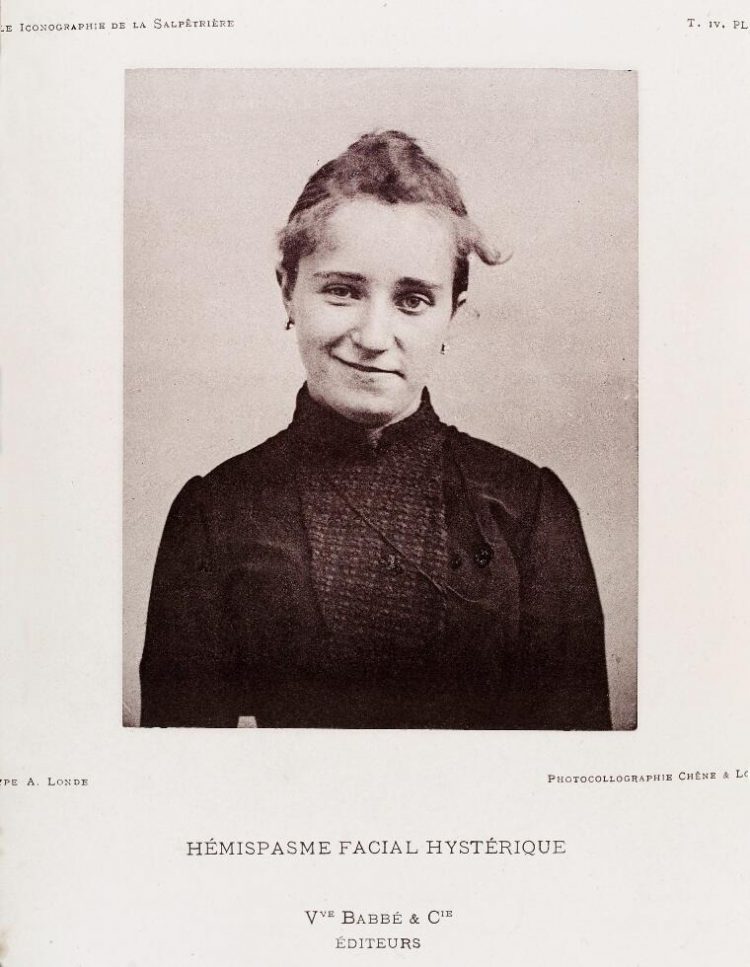

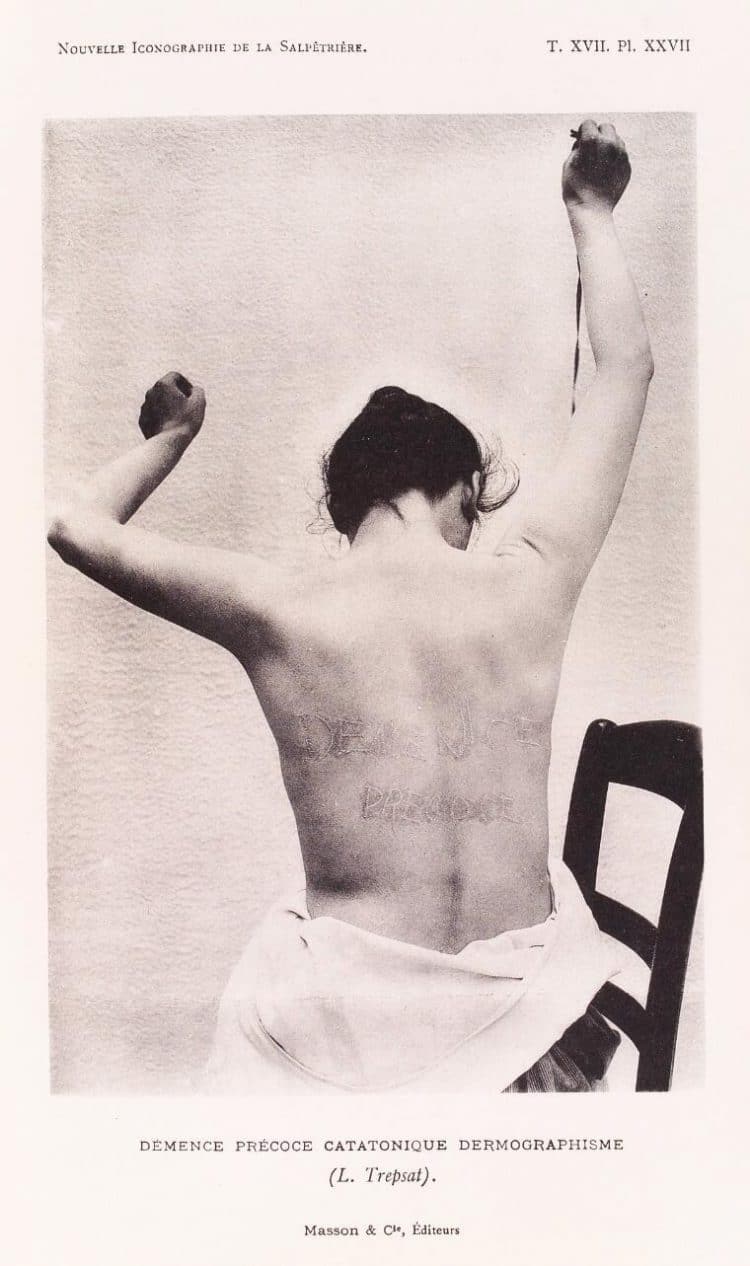

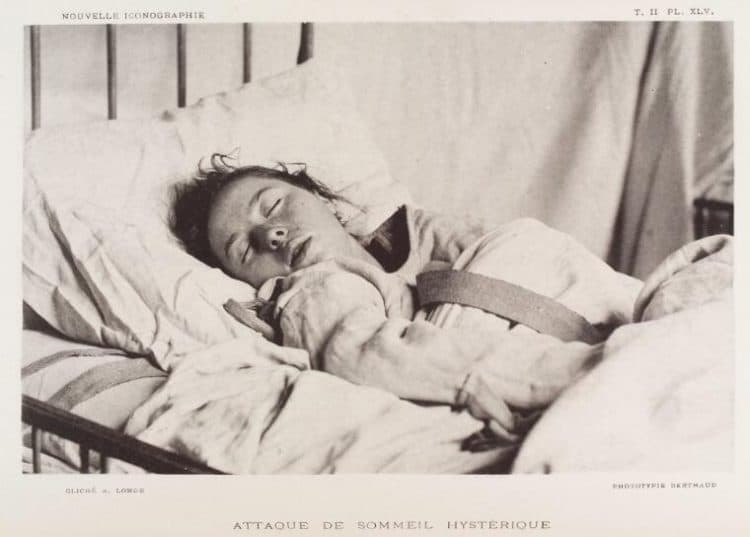

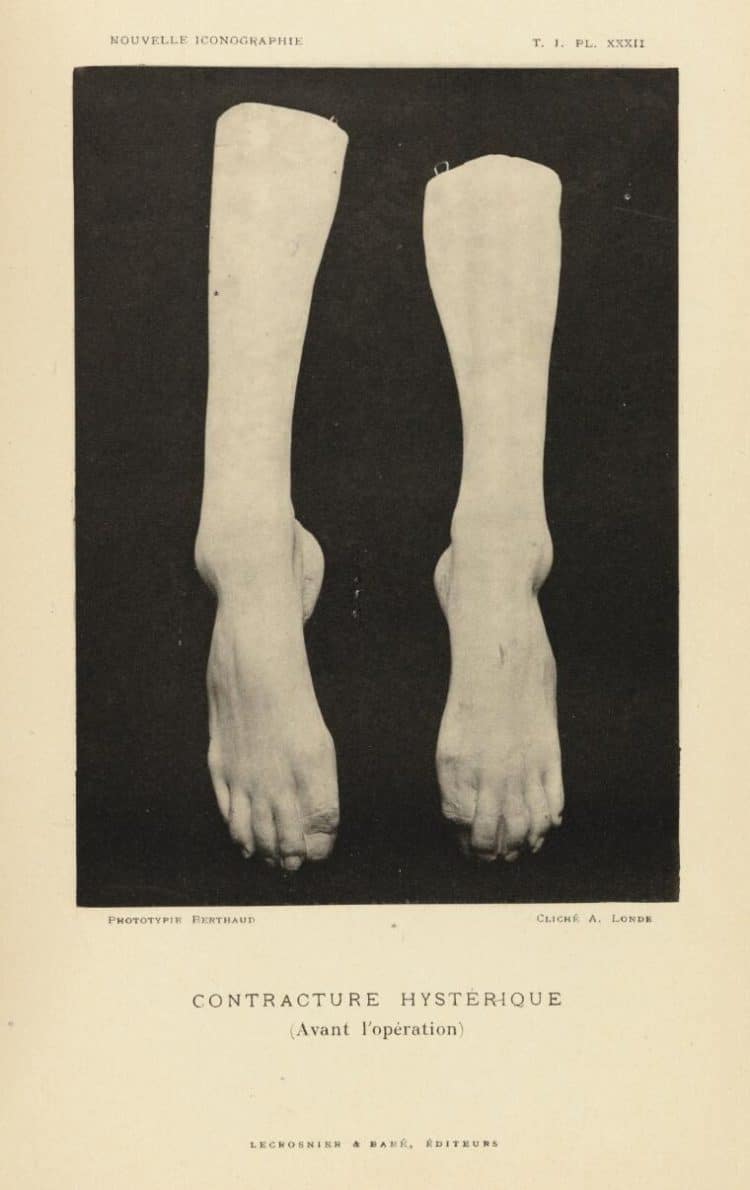

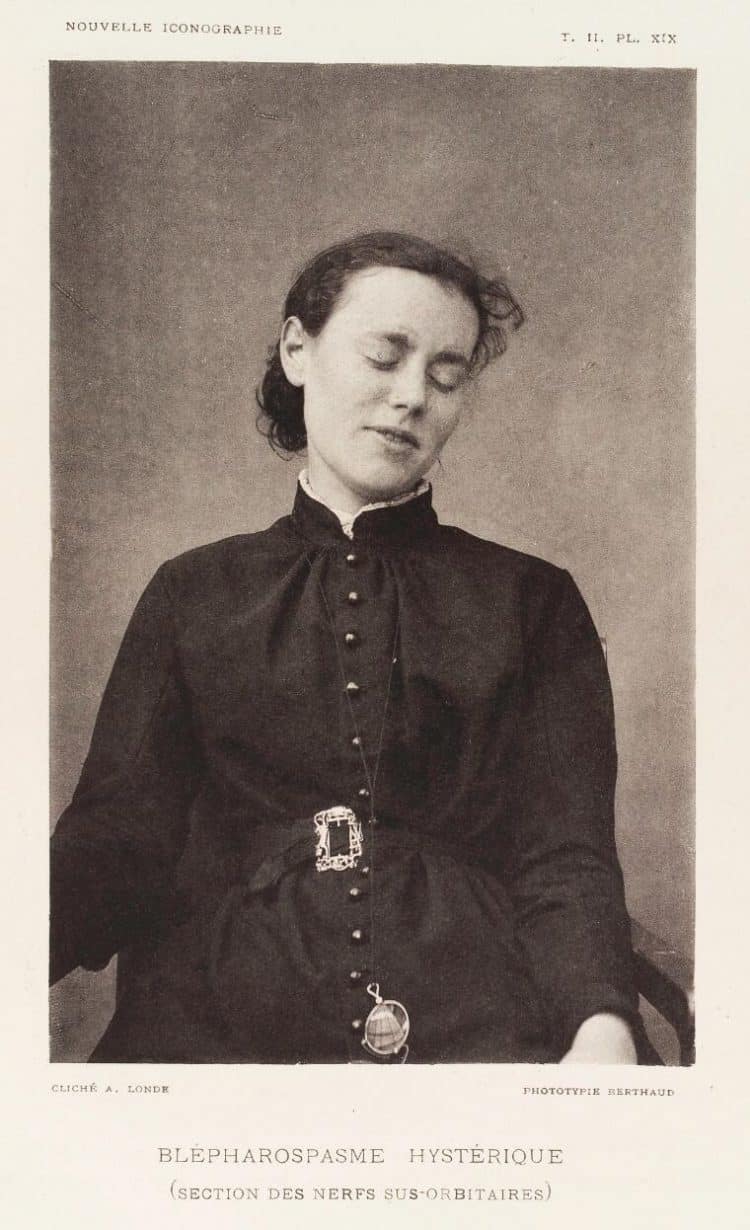

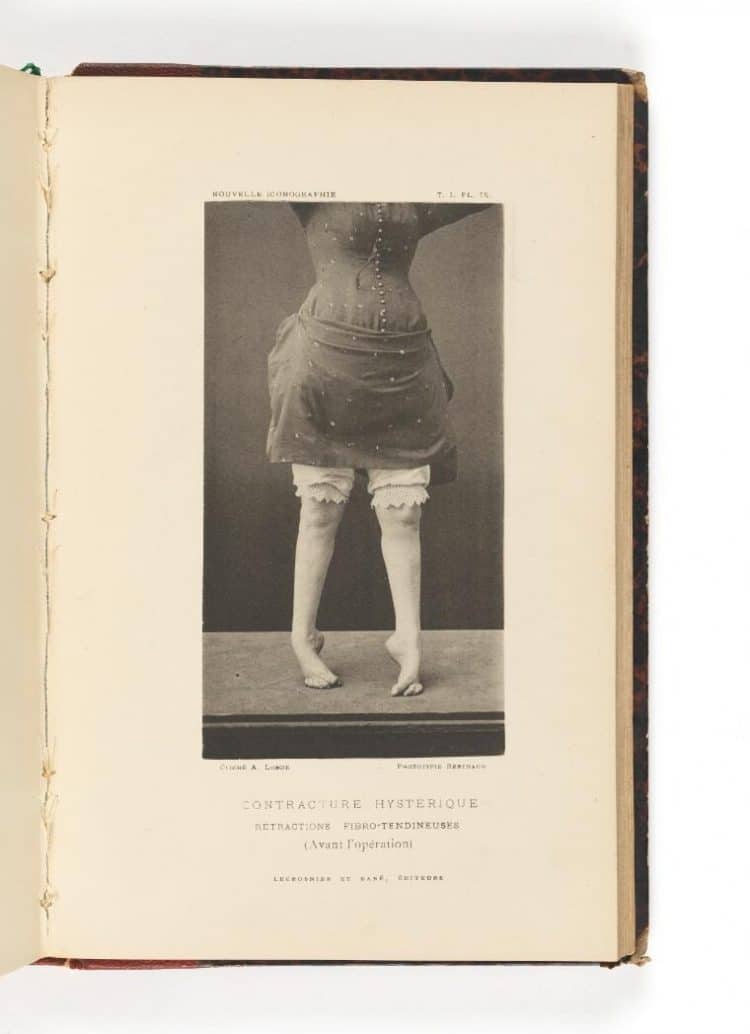

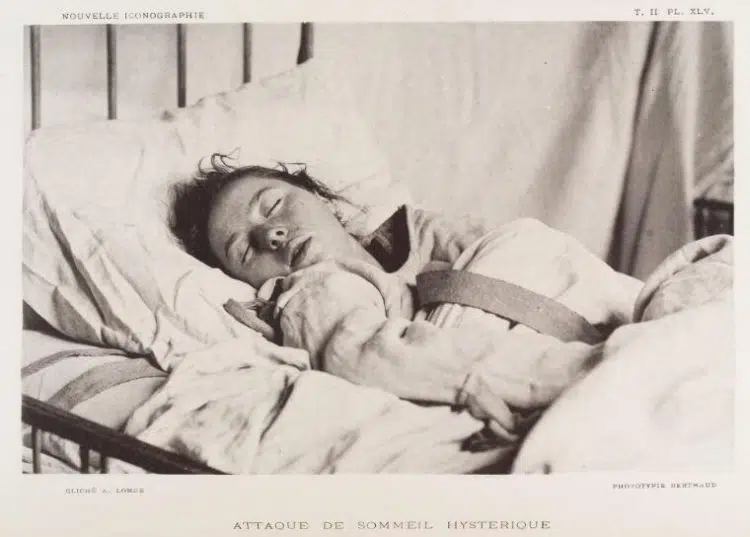

The symptoms of hysteria included shortness of breath, anxiety, insomnia, fainting, spasms, seizures, vomiting, convulsive fits, deafness, inability to speak, and more. The cures? Well, what do you think a bunch of male physicians would prescribe to suffering, mentally and physically ill women? I’ll tell you: routine marital sex (not the sex work kind); pregnancy and childbirth (fulfilling their true calling as women); “Paroxysmal convulsions” aka orgasms (hot); and last and maybe least, getting some rest (aka men leaving them the fuck alone). No wonder the Western medical industry and Big Pharma are so considerate of women’s bodies.

Charcot attempted to treat La Salpêtrière’s patients with hypnosis, since it seemed the prescribed sex and pregnancy-related treatments weren’t working. His work was highly influential on Sigmund Freud, who studied under Charcot for 4 months between 1885–1886.

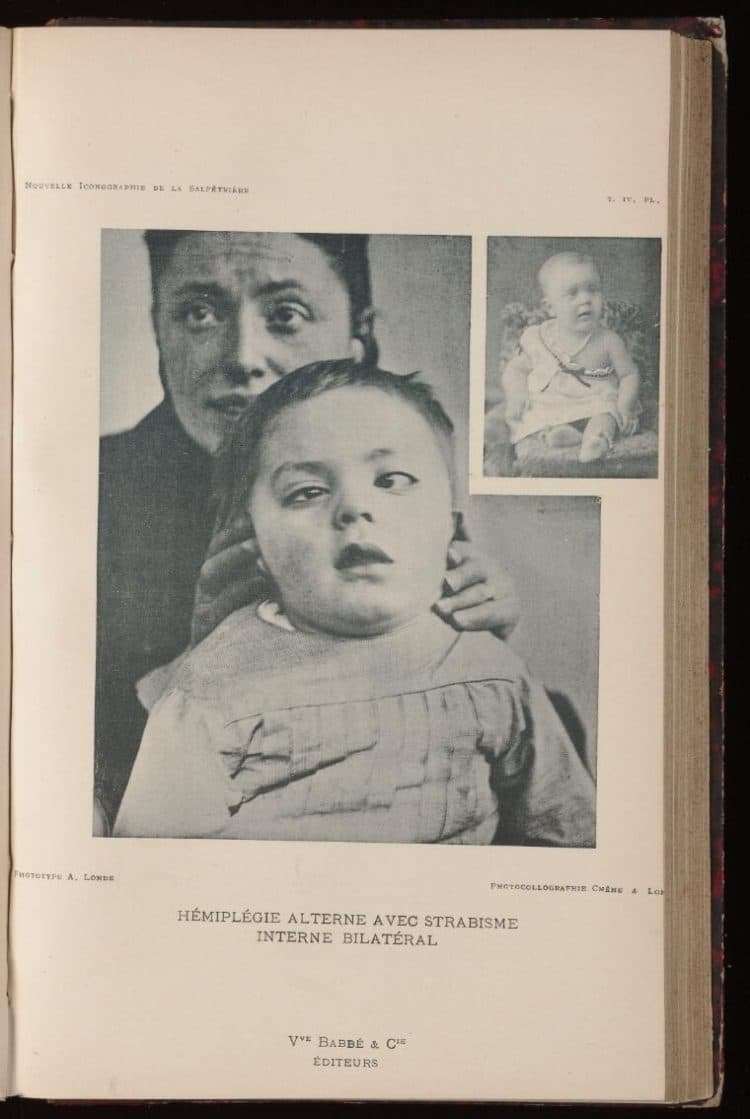

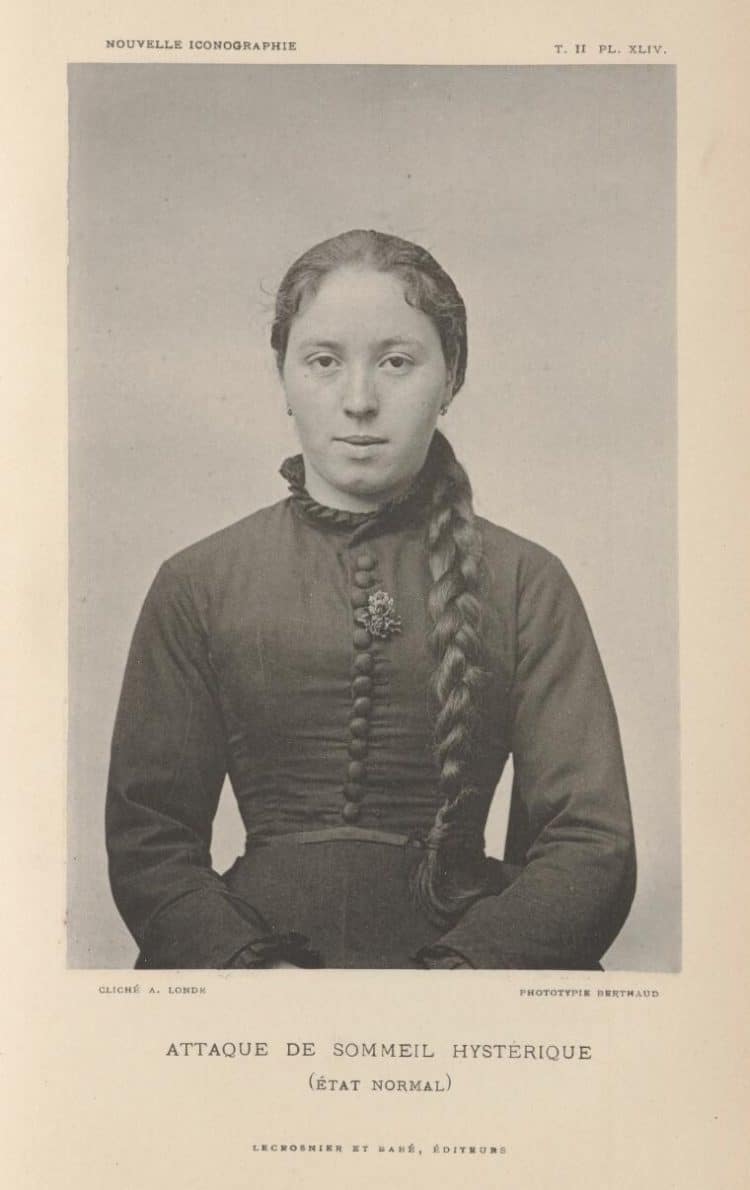

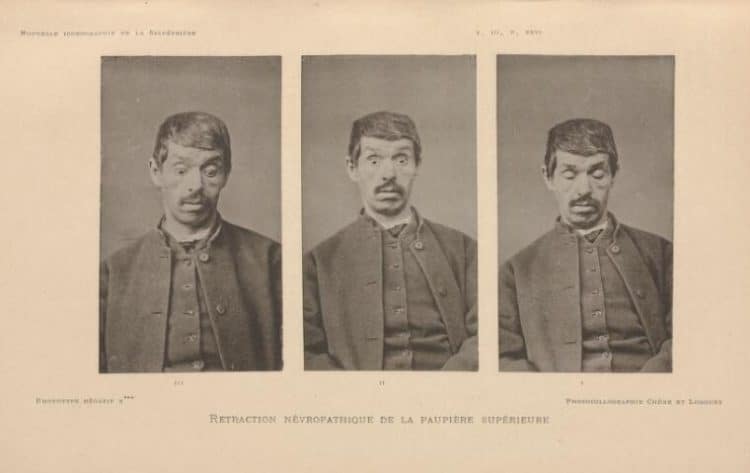

Below are a few excerpts from this era of La Salpêtrière’s long history, as well as a collection of images of its patients from the 19th Century. Imagine telling any of these women that in 150 years, girls would be pretending to be suffering from mental illness in order to get more followers on Tik Tok. The Moulin Rouge dancers may have gotten it.

Text via The Journal of Rheumatology

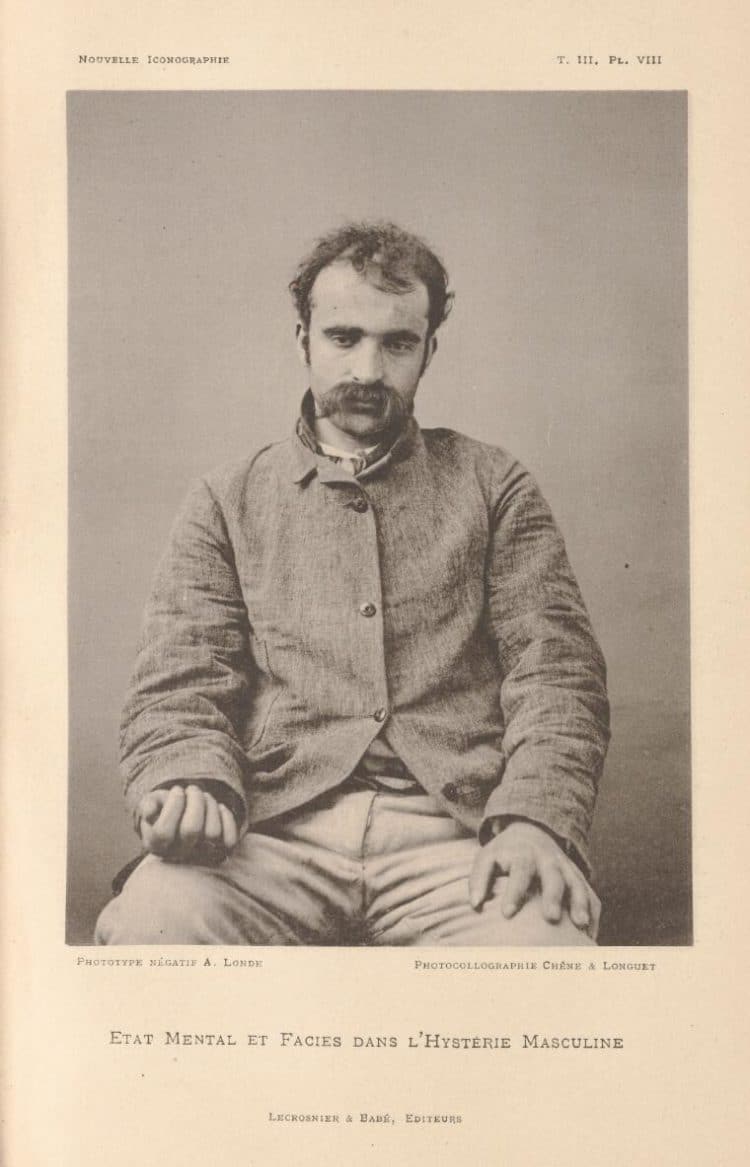

In the 19th century, the inmates of La Salpêtrière were the female dregs of society: paupers, vagabonds, beggars, prostitutes, the decrepit, senile, and insane. In the middle of that century the greatest name in the history of La Salpêtrière appeared, Jean-Martin Charcot, born in 1825. Charcot is considered by many to be the founder of modern neurology. His students constitute some of the great names in the history of that discipline. At the age of 27 he began an association with La Salpêtrière. Twenty years later, a prestigious chair in neurology was created specifically for him, a position he held until he died in 1893.

Charcot was particularly fascinated by “hysteria,” a condition that is much less common today. In his celebrated Tuesday public lectures, Charcot illustrated his findings on hysteria by live demonstrations8 (Figure 4)9. The patients put on display were young women who had found refuge in La Salpêtrière from lives of unremitting violence, exploitation, and rape. The asylum provided them with more safety and protection than they had ever known. In addition, the selected group of women who became Charcot’s star performers achieved something close to fame. It is not surprising that they put on a good show.

Jane Avril, the Moulin Rouge dancer immortalized by Toulouse-Lautrec, was admitted to Charcot’s service at the Salpêtrière at the age of 149. In her memoirs, she describes the lengths the “crazy girls” would go to in order to capture attention — to become Charcot’s “stars of hysteria.” These memoirs partially explain why hysteria was regarded as contagious.

Charcot attracted students from all over the world. At that time neurology and psychiatry had not yet separated themselves from one another, and gifted and ambitious men in these new disciplines made the pilgrimage to Paris to study with the master. Among them were Alfred Binet, William James, and an ambitious young neurologist from Vienna, Sigmund Freud. Freud’s stay at La Salpêtrière for 4 months made an indelible impression; he even named his first son after Charcot, and ultimately wrote Charcot’s obituary.

Charcot was convinced that he understood the underlying cause of hysteria. Freud once heard Charcot exclaim, very excitedly: “Mais, dans des cas pareils c’est toujours la chose génitale, toujours…toujours”. I translate this as “In cases of this type, there is always something sexual going on; always….” It is very tempting to speculate that this comment shaped Freud’s subsequent thinking.