via Flashbak

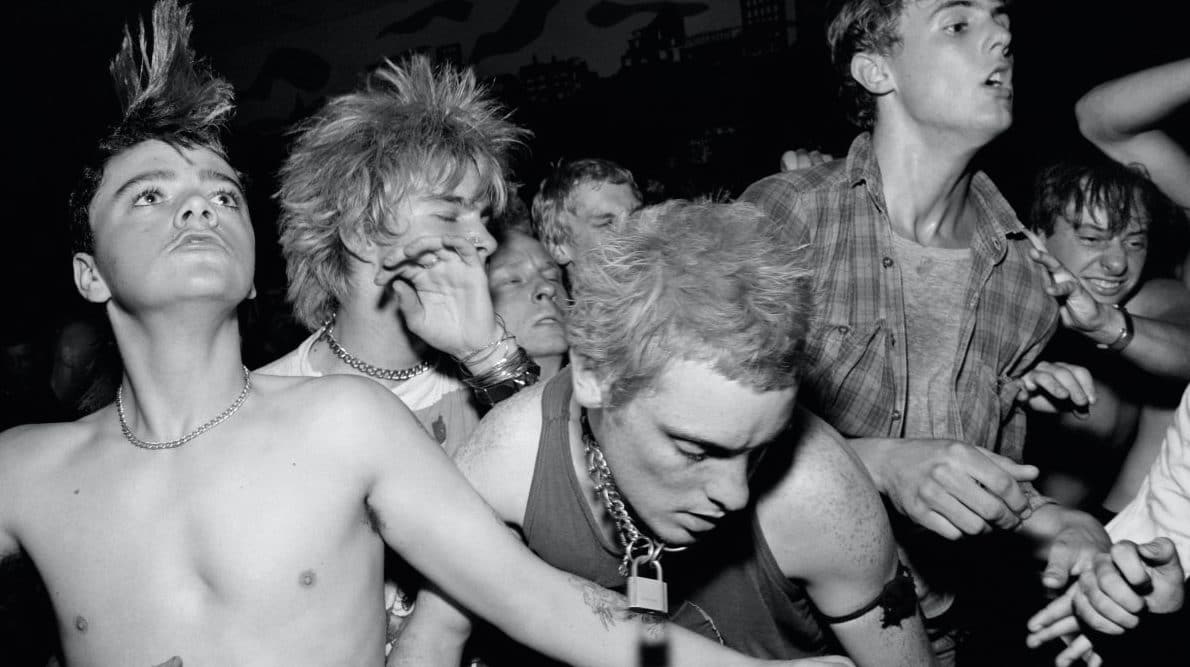

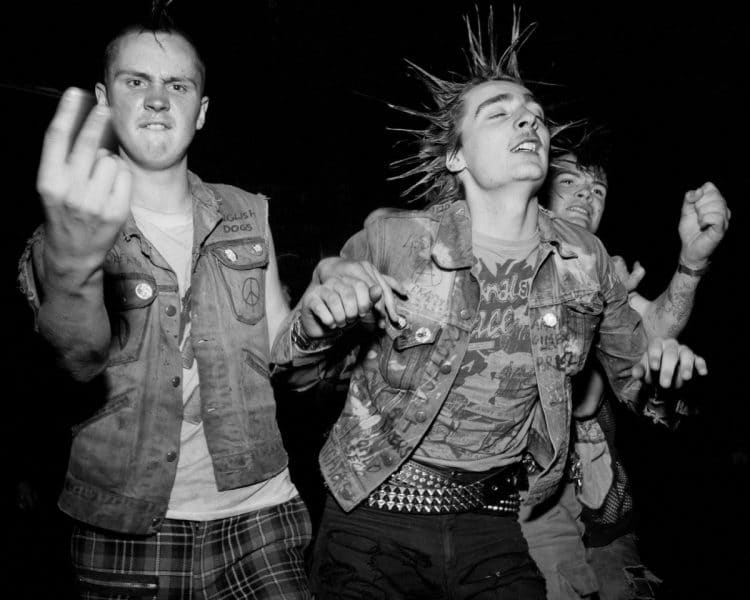

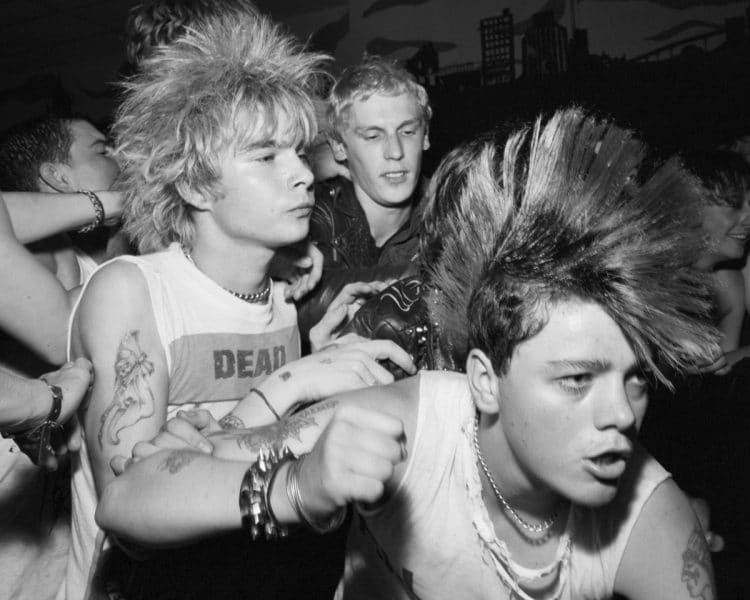

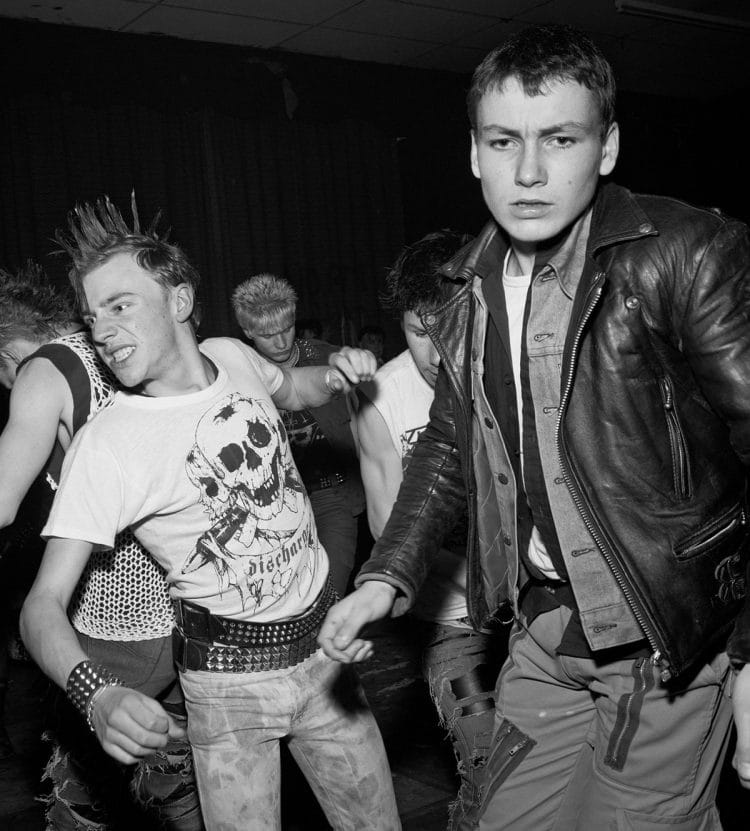

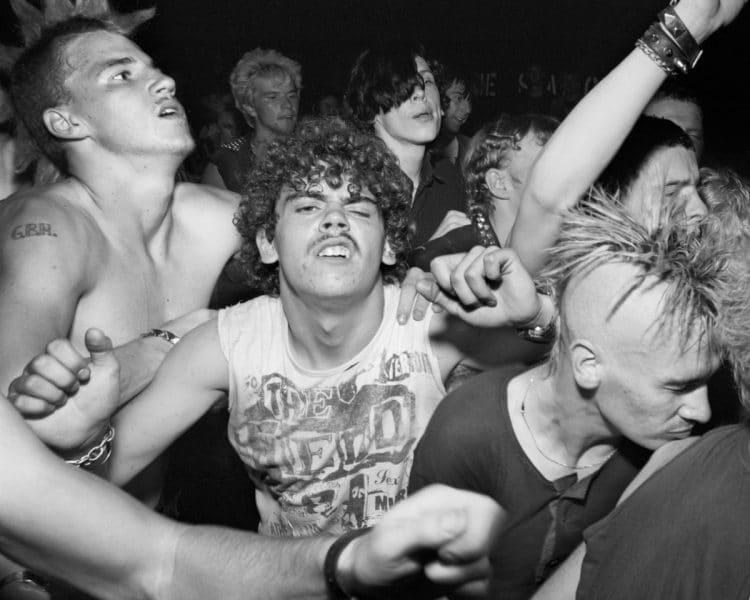

Chris Killip didn’t set out to document the anarcho-punk scene in Newcastle on Tyne in 1985. The photographer moved to the city ten years earlier on a fellowship, then stayed on until the early 90s. What attracted him most, he says, were the people “who history happened to.” Specifically, for Killip – who got his start as a beach photographer in his native Isle of Man – that meant working class people in England’s North East during the period of Britain’s de-industrialization.

Killip became known as “the photographer of the de-industrial revolution,” he says, “but it was by default. I was simply photographing what I saw.”

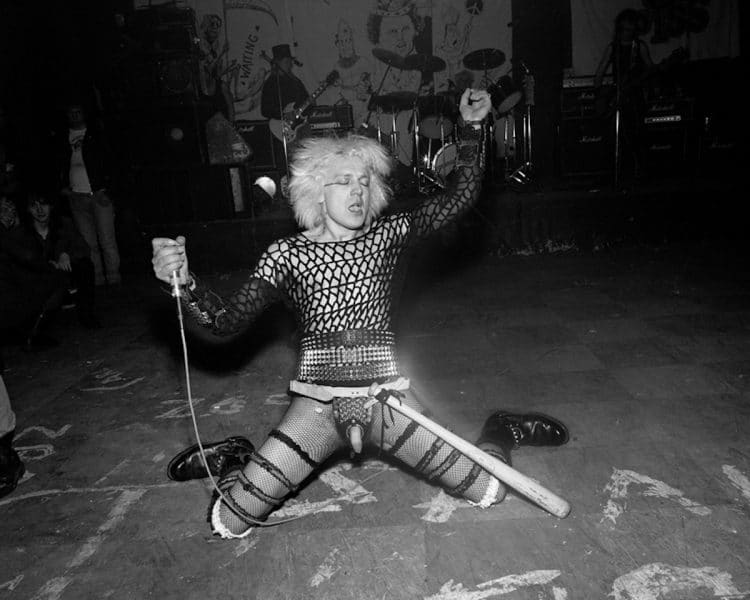

“During this period, I would also photograph things at night; venues and events. One night, somebody said I should check out The Station – an anarcho-punk venue set up in an old police social club in Gateshead – so I went along the following Saturday and was blown away by the place. It was so different to anything else because it wasn’t a commercial space. It was owned by the people who were dancing there and the bands that played there – a group called the Gateshead Music Cooperative.”

“Things were pretty depressed” at the time, Killip says. Or as Eccentric Sleeve Notes – an online archive for a local music ‘zine that ran from 1981 to 1984 – puts it: “Newcastle was a grim place in the 1980s. Unemployment was high. Culture was low. The town centre was deserted on weekday nights and if you did venture out, you had to watch yourself because the quiet streets made it more dangerous.”

Despite, or because of, the city’s decay, a thriving alternative music scene sprang up. But The Station was an anomaly, off the map. It doesn’t make an otherwise comprehensive ESN survey of 1980s Newcastle clubs. From the looks of Killip’s photos, one might make certain assumptions – that The Station, for example, was the kind of place one might be warned away from, especially if they didn’t fit a certain type.

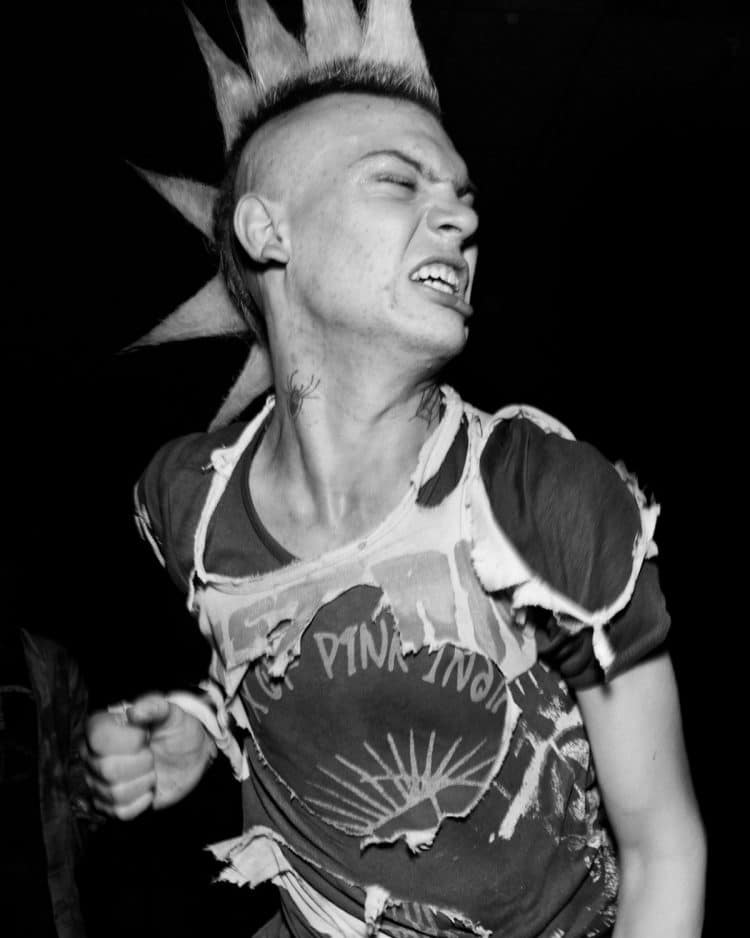

But instead of the anti-social violence wrongly associated with anarchism or rightly associated with the fascism of right-wing punk, Killip found solidarity. “These weren’t the punks of 1970s London,” he says, “these guys were politically aware. They were very keen on animal rights and would often join the miners’ strike marches…. My problem was that they only had one outfit. They were good outfits: they worked on them until they perfected their punk look. But it meant that the nights all blended into one.”