via: Res Obscura

In a previous post, I touched on the phenomenon of “cannibal medicine” in early modern Europe. It turns out that it was surprisingly common for medical patients in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to be prescribed drugs that contained human remains. These included everything from powdered human skull to more byzantine preparations like Oswald Croll’s infamous 1608 remedy which invites the reader to “take the fresh corpse of a redhaired, uninjured, unblemished man,” and “leave it one day and one night in the light of the sun and the moon, then cut into strips.”

Although historians like Richard Sugg have already written perceptively about medical cannibalism, the special role played by mummies in this story has always seemed intriguing and rather under explored to me. I spoke a bit about this at Yale’s History of Medicine colloquium last month, and thought I’d adapt some of my thoughts into a post.

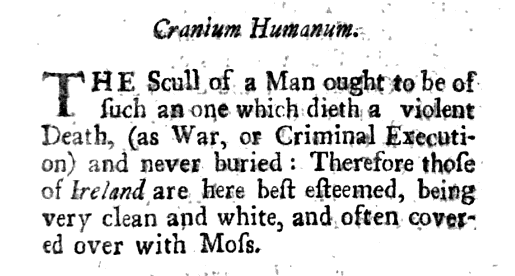

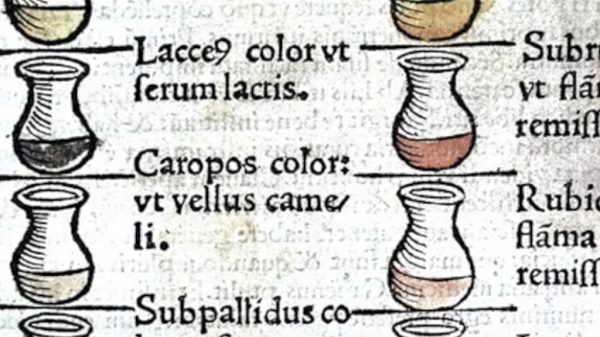

First off, it’s worth stressing that, historically speaking, there is nothing particularly bizarre about eating people. Perusing one of my favorite early modern drug manuals, John Jacob Berlu’s The Treasury of Drugs Unlock’d (London, 1690) makes it plain that a certain form of cannibalism was widely tolerated in Europe. Berlu’s guide to drugs is not at all exotic or show off-y – on the contrary, it’s a practical handbook aimed at working drugs merchants who needed to know basic facts about the wares they sold. Most of its entries involve relatively prosaic substances like tamarind, sassafras, cinnamon and elk antlers. But there are a few entries, like the one for “Cranium Humanum” shown below, which stand out to a modern eye: