Terrorism is defined as “the use of violence and intimidation in the pursuit of political aims.” Western media likes to paint terrorists with a brown face, but one of the most horrific campaigns of terror happened in the past century on American soil – the estimated 3,436 lynchings of black American men and women between 1882 and 1950, intended to control and intimidate the recently freed black population. There is nothing more disturbing than being confronted with visual evidence of humanity’s dark heart, especially when it is evidence of a widespread, mainstream hatred for and violence towards one another. Hatred that stems from fear, and is driven by religion and a belief that murder is morality made distorted flesh; violence that aims to cow and suppress any aspirations a community might have for equality and a brighter future.

When I came across this collection of American postcards from James Allen and John Littlefield, published in a book entitled Without Sanctuary, I saw how important it is to look at these images, today more than ever. These postcards were made to commemorate events that made many American white people feel proud – of their race, of their superiority, of their civilization and their intelligence. They took photos of their disgusting, cowardly accomplishments and memorialized them for future generations, to be found and collected and remembered by their descendents. On the backs, they wrote to friends and family in sociopathic excitement about the mob the participated in. These postcards capture the mobs witnessing with glee the murder of young men and women, whose most serious crime was the color of their skin. The corpses hanging and charred in these postcards lived in a world that counted down the days until their murder from the second they drew air into their infant lungs. This history is potent, stomach-churning and of essential importance to the America of today, and to the world of today. And the most striking thing about these photographs is that they don’t erase the perpetrators like many histories and memorials do today, preferring to focus on who was victimized rather than on those who proudly – and with government backing – tortured, raped and murdered people. The murderers in these photos stand proud, grown men looking at the camera with the smiling conviction that the teenage boy they just killed, one against a hundred, was deserving of their hatred, fear and frustration. No grand jury needed; the law was in the hands of the murderers.

History is not linear; history is happening all around us, all the time. These photos are context, they are reality, they are pictures of American terrorism. Read James Allen’s commentary below and be aware that these photos are sickening, and all too real.

The lynching of nineteen-year-old Elias Clayton, nineteen-year-old Elmer Jackson, and twenty-year-old Isaac McGhie. June 15, 1920, Duluth, Minnesota.

Text by James Allen

I am a picker. It is my living and my avocation. I search out items that some people don’t want or need and then sell them to others who do. Children are natural pickers. I was. I played at it when I collected bees in jars that were dusting blossoms in the orange groves surrounding my family’s home, or when I was wandering along swampy lakesides and hidden banana groves and found caches of stolen liquor or mossy old canoes.

My father would bring home bulging canvas sacks stenciled with bank names, bags of copper pennies or weighty half dollars and we kids would sit around the mounds of coins as if around a camp fire and shout bingo sounds when we found an S penny or silver fifty cent piece. At fourteen years of age, I used those coins to run away, searching for the lush drifting continent that existed only in my mind, where the people spoke in cryptic tongues, and feasted on honey and sling-shotted gem-feathered birds, sleeping at ease under open skies. I never found that place, but the police found me and shipped me back home. Picking, I guess, is a kind of extenuation of that search.

Once, unthinkably near to our house, in a deep, waxy green grove, I followed a path to the mildewed shack of an unshaven, alcoholic hermit. He made fantastic drip paintings on a portable turntable that splattered pure liquid color outwards like sun rays. Years later a taxicab pulled up to the curb in front of our house and rolled the old man out on to the street like a duffle bag of dirty laundry. He lay still, good as dead. This was my first grappling with the concurrence of beauty and pain, art and the hidden.

Mothers don’t counsel their sons to be pickers. No adult aspires to be called a picker. In the South it is a pejorative term. He is thought to be a salvage man, lowly and ignorant, living hand to mouth, maybe a thief that doubles back at night and steals what couldn’t be bought outright for pennies. I have tried hard to bring some dignity to the work, traveling countless roads in my home state, acquiring things that I thought were telling – handmade furniture and slave-made pots and pieced quilt tops and carved walking sticks. Many people who sell me things are burdened with their possessions, or ready for the old folks home or pining for the grave. Some are reluctant sellers, some eager. Some are as kind and gentle and welcoming as any notion of home, some are mean and bitter and half crazy from life and isolation. In America everything is for sale, even a national shame. Till I came upon a postcard of a lynching, postcards seemed trivial to me, the way second hand, misshapen Rubbermaid products might seem now. Ironically, the pursuit of these images has brought to me a great sense of purpose and personal satisfaction.

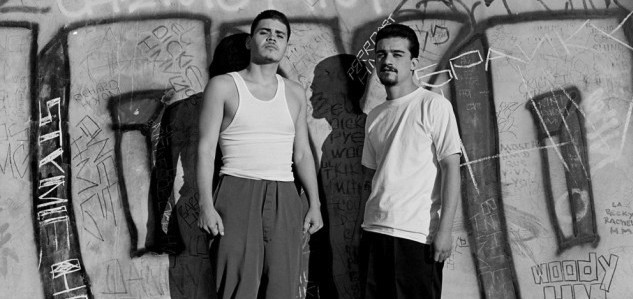

The lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, a large gathering of lynchers. August 7, 1930, Marion, Indiana.

Inscribed in pencil on the inner, gray matte: “Bo pointn to his niga.” On the yellowed outer matte: “klan 4th Joplin, Mo. 33.” Flattened between the glass and double mattes are locks of the victim’s hair.”

Charred corpse of Jesse Washington suspended from utility pole. Reverse reads “This is the barbecue we had last night my picture is to the left with a cross over it your son Joe.”

May 16, 1916, Robinson, Texas.

Studying these photos has engendered in me a caution of whites, of the majority, of the young, of religion, of the accepted. Perhaps a certain circumspection concerning these things was already in me, but surely not as actively as after the first sight of a brittle postcard of Leo Frank dead in an oak tree. It wasn’t the corpse that bewildered me as much as the canine-thin faces of the pack, lingering in the woods, circling after the kill. Hundreds of flea markets later a trader pulled me aside and in conspiratorial tones offered me a second card, this one of Laura Nelson, caught so pitiful and tattered and beyond retrieving – like a child’s paper kite snagged on a utility wire. The sight of Laura layered a pall of grief over all my fears.

I believe the photographer was more than a perceptive spectator at lynchings. The photographic art played as significant a role in the ritual as torture or souvenir grabbing – a sort of two-dimensional biblical swine, a receptacle for a collective sinful self. Lust propelled their commercial reproduction and distribution, facilitating the endless replay of anguish. Even dead, the victims were without sanctuary.

The lynching of J. L. Compton and Joseph Wilson, vigilantes. April 30, 1870. Helena, Montana.

Printed inscription in upper right hand corner reads, “Hangman’s Tree, Helena Montana.” Another version of this card states, “More than twenty men were hanged upon this tree during the early days.”

The bludgeoned body of an African American male, propped in a rocking chair, blood splattered clothes, white and dark paint applied to the face and head, shadow of man using rod to prop up the victims head. Circa 1900, location unknown.

These photos provoke a strong sense of denial in me, and a desire to freeze my emotions. In time, I realize that my fear of the other is fear of myself. Then these portraits, torn from other family albums, become the portraits of my own family and of myself. And the faces of the living and the faces of the dead recur in me and in my daily life. I’ve seen John Richards on a remote county road, rocking along in hobbyhorse strides, head low, eyes to the ground, spotting coins or rocks or roots. And I’ve encountered Laura Nelson in a small, sturdy woman that answered my knock on a back porch door. In her deep-set eyes I watched a silent crowd parade across a shiny steel bridge, looking down. And on Christmas Lane, just blocks from our home, another Leo, a small-framed boy with his shirttail out and skullcap off center, makes his way to Sabbath prayers. With each encounter, I can’t help but think of these photos, and the march of time, and of the cold steel trigger in the human heart.

Silhouetted corpse of African American Allen Brooks hanging from Elk’s Arch, surrounded by spectators. March 3, 1910. Dallas, Texas.

Printed inscription on border, “LYNCHING SCENE, DALLAS, MARCH 3, 1910”. Penciled inscription on border, “All OK and would like to get a post from you, ‘Bill.’ This was some Raw Bunch.”

Reverse of card reads “Well John–This is a token of a great day we had in Dallas…a negro was hung for an assault on a three year old girl I saw this on my noon hour. I was very much in the bunch.”

The corpses of five African American males, Nease Gillepsie, John Gillepsie, “Jack” Dillingham, Henry Lee, and George Irwin with onlookers.

August 6, 1906. Salisbury, North Carolina.

Postcard from lynching of Will James, Cairo, Illinois 1909

Bennie Simmons, alive, soaked in coal oil before being set on fire. June 13, 1913. Anadarko, Oklahoma.

Etched into negative, “Edies Photo Anadarko Oklo”

The lynching of Leo Frank. August 17, 1915, Marietta, Georgia.

Superimposed over the image: “the end of leo frank hung by a mob at marietta. ga. aug. 17. 1915.”

Images of the lynching of Frank Embree, Fayette, Missouri 1899

See the full collection at Without Sanctuary