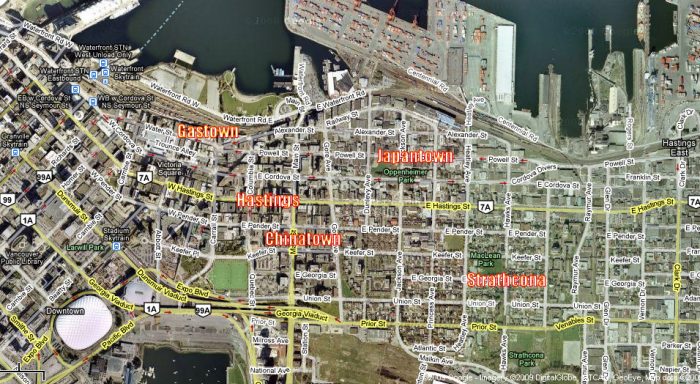

The Downtown Eastside (DTES) was once called Kem Kem a-Ley, the Place of the Maples. Since time immemorial the xwməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwu7mesh (Squamish), Tsleil-Waututh Nations would come and collect maple for paddle making, essential for sea and river faring peoples. In colonized memory, it was a mill; then Japantown; then Skidrow; and now we have the DTES. Not so much a location as a label. People who live here are considered by the general public to be addicted, homeless, impoverished – Vancouver’s needy and unwashed. The poorest, most deadly postal code in Canada outside of a forced Reservation System. I have said my sister lives in the Downtown Eastside, only to met with looks of sympathy and coo’s of, “Oh gosh, is she okay?” I realized the response showed our collective understanding of who lives in this place and what they might be doing. My sister, a teacher at a local high school, lives with her family in Railtown, and is fine, thank you very much. Multiple understandings, one location.

Pre-DTES map of Vancouver

Traditionally, addiction has been considered a lack of moral fibre, an ethical disfunction or a lack of will power. So-called moral and ethical reactions to addiction have created policies like prohibition, the war on drugs, and enforcement. The enforcement of these policies have backfired, and ended up hurting the people they were meant to safeguard. I summarize Vancouver poet-warrior Bud Osborn’s protests in “Raise Shit” – what happens when a war on drugs is waged, it becomes a war on addicts. Meaning we lose sight of an individual’s life in the virulent turmoil of trying to sort out a moral codification around addiction and who’s at fault. This code is built on social class, identity and location. A suburban opioid overdose of a middle class parent is a tragedy. A opioid overdose interurban denizen near East Hastings is an arm’s length statistic.

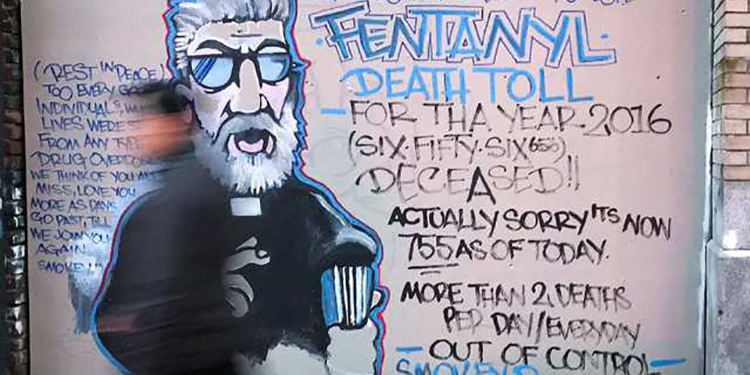

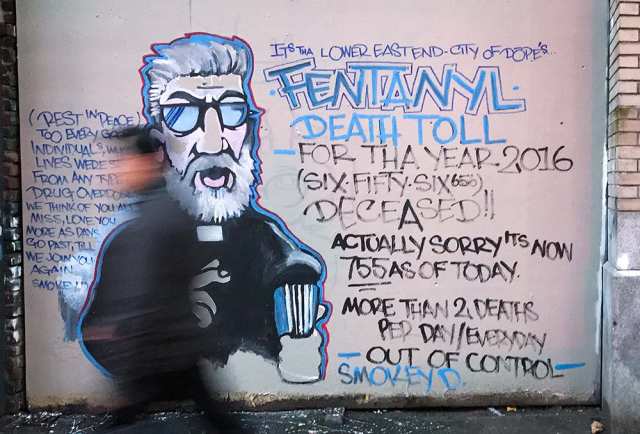

In North America, we have an unprecedented crisis. The illicit drug trade has been flooded by fentanyl. Fentanyl is a drug that being found in 67 percent of overdoses in British Columbia. On December 2, 2016, the Vancouver Police Department (VPD) stated that 100 percent of drugs tested from the DTES have tested positive for fentanyl and its more deadly cousin, carfentanyl. Drug users, community groups, community-based activists, medical and health professionals, emergency care providers are scrambling to limit the impact from the arrival of fentanyl. Saying the morgue is at capacity is an understatement.

Photo: NICK PROCAYLO / Vancouver Sun

In Vancouver, agencies like Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU), Portland Hotel Society (PHS), and Drug Users Resource Center (DURC) have worked hard for the past 20-plus years to humanize the folk who use substances. Community-based action groups and agencies work hard to address the stigma of addiction. If it wasn’t for the community engagement already in place in Vancouver, the fentanyl crisis would have a much greater toll across British Columbia.

The Emergency Opioid Summit in Ottawa had many politicians scrambling to brush up on the drug policy stances of their parties. According to many service providers, the results of the two day conference have now completely missed the mark. Across Canada, 94 percent of drug strategy dollars are spent on enforcement. And enforcement is Ottawa’s main plan to cope with the overdose deaths in British Columbia so far this year, which at the time this article was written is 730 people. 140 people in B.C. died in November, most of those were community members of the DTES. In 2016, we saw a 227 percent jump in overdose deaths from the year before. Since January 1, 2016, one person dies every 10-12 hours. Thus far, British Columbia Premier Christy Clark’s call for enforcement has done nothing to stem the tide. On the other hand, the introduction of naloxone, naloxone training, and education has made a huge difference for DTES community members and their allies. VANDU has volunteers patrolling the alleys day and night, the PHS made bike teams for alley response, DURC is now a rapid overdose response site. There are pop up tents that have been running for the past 9 weeks – seven days per week, 24 hours per day.

Overdose deaths and prohibition and are not new in Vancouver. A busy port town, Vancouver has seen more than its fair share of prohibition, prostitution, and drug trade. The first restriction from the 1850s was a prohibition against selling liquor to the Indigenous and Aboriginal peoples, eventually leading to three and a half years of general prohibition ending in 1921.

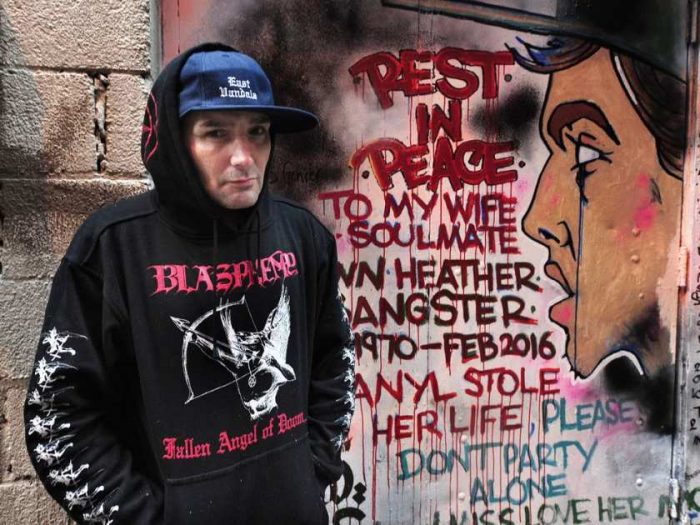

Grafitti Artist Smokey D. / Photo: NICK PROCAYLO / Vancouver Sun

Consumption of alcohol did fall at the beginning of prohibition, but it subsequently increased. Results of prohibition? Alcohol became more dangerous to consume; crime increased and became organized; the court and prison systems were stretched beyond capacity; corruption of public officials was rampant. No measurable gains were ever marked from the policy. The most salient criticism about the failure of prohibition was that it led many drinkers to switch to opium, marijuana, patent medicines, cocaine, and other dangerous substances that they would have been unlikely to encounter in the absence of Prohibition. Currently, we call this switch and its consequences The Balloon Effect. In essence, The Balloon Effect is a metaphor describing the movement from air inside the balloon from one area to another when being squeezed; usually through the path of least resistance. There are always human tolls and unforeseen consequences caused by the enforcement of drug policies.

Let’s examine The Balloon Effect in relation to the increase in fentanyl addiction and death rates among drug users after oxycontin was taken off the market. We won’t talk about how Purdue Pharma nudged their numbers and drug descriptions around to make oxycontin seem much less addictive than it was. And we won’t talk about the FDA giving doctors permission to prescribe oxycontin to patients as young as 11 years old. We won’t illuminate the class action fraud suit and 600 million dollar payout. We won’t look the 11 billion dollars per year that Purdue made from its honey pot drug over 12 years. We won’t discuss the disregard for life or the consequences for the millions of people prescribed oxycontin. What we will touch on is the replacement of fentanyl in prescription use for chronic and severe pain. One swift balloon squeeze, and we can jump forward to a world where people who just wanted to get a high for the weekend – used to the effects of recreational oxycontin – now die, leaving their children orphaned. A world where if you use illicit or prescribed drugs, you take the risk of dying multiple times per day. A world where if you are in chronic pain, it becomes hard to find a doctor who would be willing to give you care; forcing you to find other avenues for pain relief. A world where prescription opioids are the number one cause of accidental death in the U.S., with 18,893 overdose deaths related to prescription pain relievers, compared to 10,574 overdose deaths related to heroin in 2014. A world where enforcement doesn’t make a difference in a crisis, but long term treatment planning, community-based action and public education does. Alas, community-based peers and volunteers were not invited to the government’s two day summit on the opioid crisis in Canada.

Intersection of Main St. & Hastings St. in the DTES / Vancouver Sun

Wanting to understand more, I sat and talked with nurse Sarah P., who works primarily in the DTES. She is someone who has reversed hundreds of overdoses, can prescribe naloxone, and trains community members to administer naloxone. She is a frontline expert. Sarah explained to me that the most exciting changes that have happened in drug policy in Vancouver over the past seven years is the availability of naloxone prescriptions. “Now even pharmacists can give it, which I think is beautiful because everyone should have access to it,” she says. At one time, only doctors could prescribe naloxone; then over the past many years Registered Nurses began to prescribe, and now pharmacists. Sarah sees a community that has access to and training in naloxone as a community that can begin to deal with this public health emergency. Since April 14, 2016, B.C. has been officially in a state of medical emergency. “The community can respond when trained,” says Sarah. She describes being called to respond to an overdose in the community and as she was heading toward it, people were breathing for the fallen and had called 911 by the time she had gotten there. “The difference between stage one and two of an overdose,” says Sarah, “is oxygen.” Hypoxia, or oxygen deficiency, causes brain injury, and eventually death. People knowing how to get oxygen into someone who has overdosed can be life saving.

I asked Sarah to walk me through an overdose and reversal. “Basically, opioids are a depressant that suppress the central nervous system.” She went on to say that because of the suppression, the breathing reflex is slowed down and carbon dioxide begins to build up in the body. Normally, a buildup of CO2 triggers an automatic reflex, forcing the body to breathe. “In the case of opioid overdose, it slows or stops that response.” Sarah states that sometimes when naloxone isn’t at hand, they can keep a person alive by ‘bagging them’ until naloxone arrives – a term used to describe an airway opener and hand bag apparatus. Depending on how deep the overdose, a Stage One might be revived by rapping knuckles on the sternum to stimulate the pain response, which can rouse some overdoses. Sarah said when she began working downtown, she would begin with a half a vial of naloxone. More recently people who are overdosing need three or four vials of naloxone to be revived.

The introduction of fentanyl into the DTES community has caused a shift in the way that people are needing naloxone. For starters, it is not only opiate injection users who are overdosing. Sarah says that according to the drug testing at Insite (North America’s first legal supervised drug injection site, located in the DTES), fentanyl is showing up in 90 percent of the substances tested. Fentanyl is in crack cocaine and crystal methamphetamine, as well. People are overdosing from snorting and smoking it. Consequently, more people need access and training for naloxone.

Via Megaphone

I asked Sarah what risks are associated with using naloxone. She said unequivocally, “Not using it is really the main challenge to an overdose reversal … It is so easy to reverse having narcan [naloxone] and oxygen on hand.” She goes on to let me know that people cannot abuse naloxone. Naloxone binds to the opioid systems in the brain, “it has a greater affinity than the opiate … it bumps the opiate from acting on the pathway … the opiate is there, it just stops from working.” So basically, it is an anti-opiate that wears off quicker than the life of an opioid, so people need to be careful once they have had a reversal. They might experience withdrawal and try to use again right away, which causes another overdose once the naloxone wears off. Simple monitoring and support can help people through that transition more safely. Sarah stated that if I, as a non-opiate user, was to attempt taking multiple doses of naloxone, the only thing that would happen to me is my liver and kidneys would have to work harder, but my brain chemistry would not be shifted in any way.

In Vancouver between November 17th-18th, 2016 – in less time than the Emergency Opioid Summit took place in Ottawa – frontline staff at shelters, housing projects and Insite report reversing over fifty opioid overdoses. On Sunday, November 20th, frontline staff, volunteers and peers reported over 90 overdoses in one day. Community-based activists are being told they are exaggerating. However, the people on the street say there hasn’t been a break in the sound of sirens. They say the wailing and flashing lights are constants. People are literally dropping onto the cement. Insite is working at full capacity. But they can’t cover all consumption routes, either.

Photo: NICK PROCAYLO / Vancouver Sun

As a human rights reaction to this unprecedented death toll, community-based, unsanctioned, peer-supervised consumption tents have ‘popped up’ in the back alleys of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES). The VPD have issued a special report stating that substance users should access harm reduction services as there is a life threatening risk from the carfentanyl and fentanyl. Fentanyl is already 50-100 times more toxic than other opioids. Carfentanyl, an elephant tranquilizer, is 10,000 times more toxic than morphine, 100 times more potent than fentanyl, and is also making it onto the streets.

In November, simultaneous to the warnings being posted about drugs, the police were telling consumption popup tents they are in violation of fire lane codes. In November, the VPD were threatening to tear them down. Vancouver Coastal Health had admonished the popups, stating they are against the law and that there is no support or funds available to help the volunteers running them. In Novemeber, VCH was waiting for their licensing on three new supervision sites, which had not yet been approved.

December, 12, 2016: the leash is finally off. That week, the Federal government tabled Bill C-37, which essentially gives permission for Health Authorities to take action without reprisal. Vancouver Coastal Health has brought their emergency tent and staff to a freshly paved lot next to the original Portland Hotel building on Hastings. All Community VCH staff will be able to administer naloxone after being trained. There are plans for three new consumption sites to be up and running before January. Everyone I spoke to who has been working amid the crisis is grateful for the reprieve and support. Very few are willing to critisize the progress, but as an observer of this crisis, it is too late for so many.

Photo: NICK PROCAYLO / Vancouver Sun

Over the past 20 years in Vancouver, grassroots, community-based action has been the only effective answer to extending life in the DTES and raising the quality of the lives saved. The research and work that people have done in this area had lead to influencing life saving protocols across Vancouver, B.C. and beyond. Access to services and a spectrum of care are key. Community education, multi-directional approaches and long term treatment plans can help unsettle the moral codification which barriers the minds of and consequently their policies. The code words are addiction, addict and recovery. Health Care, Addiction and Mental Health.

My best friend died of an opioid overdose. She was a vibrant and passionate person. Dichotomous, she was alive to the world and she suffered greatly. She had an intolerance to pain that made numbing by opioid appealing; heroin, if she could get it. One day, she took too much. She died alone in her locked apartment. I was on the other side of the locked door and couldn’t convince the emergency responders to act fast enough, according to my count of time. She was a person in a complex situation, not a junkie, not a criminal. Law enforcement did little to help her in that moment she clung to the edge of breath. If we knocked the ‘shame’ of addiction off the table, if she wasn’t isolated. Instead, if she had a person with her and naloxone, she might be here today — maybe. If we could see people in her position as people and not labels, what a different way we could be approaching this North American epidemic.