Science is extremely weird. So is medicine. Both of these practices claim to have iron-clad codes of ethics, and yet there are countless examples of those ethics being violated, in the past and today. Animal experimentation, human experimentation — if they can justify it, or hide it, it will happen. Case in point is the Dolphin Point laboratory on the Caribbean island of St. Thomas, a NASA-funded project to communicate with dolphins. Its founder, Dr. John Lilly, was obsessed with dolphins. Specifically, the idea that dolphins could communicate with humans. He built Dolphin Point in the early 1960s, with the support of influential scientists like Carl Sagan and Gregory Bateson. The dolphins, who were the actors from the movie Flipper, lived outdoors, and Dr. Lilly spent his days observing and attempting to talk to the dolphins, known as Peter, Pamela, and Sissy. Then Margaret Howe Lovatt came along and took it a step further.

Sissy was the biggest. Pushy, loud, she sort of ran the show. Pamela was very shy and fearful. And Peter was a young guy. He was sexually coming of age and a bit naughty.

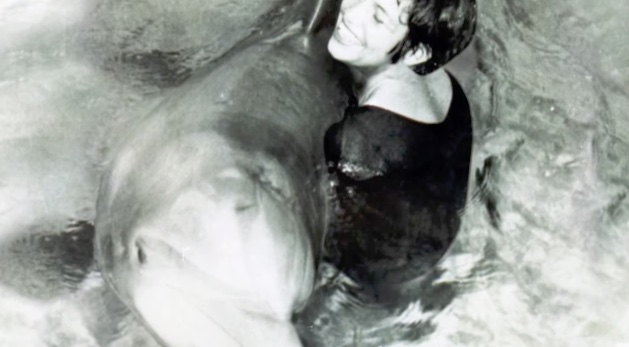

Margaret Howe Lovatt

Lovatt, not a scientist or an expert on dolphins, heard about the house and came by to see if they needed a volunteer who was exceptionally passionate about dolphins. Dr. Lilly noticed her intuitive knowledge of dolphin speak, and she began to regularly volunteer to work with and teach the dolphins English vocabulary. In particular, she focused on teaching Peter, but she felt that he wasn’t making enough progress in their regular lessons. So in 1965, she decided to move in with him. She and Dr. Lilly set up an indoor aquarium at Dolphin Point where she and Peter could live together, and they could work on their English 24/7.

Human people were out there having dinner or whatever and here I am. There’s moonlight reflecting on the water, this fin and this bright eye looking at you and I thought: ‘Wow, why am I here?’ But then you get back into it and it never occurred to me not to do it. What I was doing there was trying to find out what Peter was doing there and what we could do together. That was the whole point and nobody had done that.

Margaret Howe Lovatt

After a couple of months of living together, Lovatt noticed that Peter seemed sexually interested in her. He would get excited and rub himself on her — which at first would get him sent back outside with Sissy and Pamela. One day, however, Lovatt decided it would be easier to continue if she just…helped him out.

I wasn’t uncomfortable with it, as long as it wasn’t rough. It would just become part of what was going on, like an itch – just get rid of it, scratch it and move on. And that’s how it seemed to work out. It wasn’t private. People could observe it.

Margaret Howe Lovatt

Peter was right there and he knew that I was right there. It wasn’t sexual on my part. Sensuous perhaps. It seemed to me that it made the bond closer. Not because of the sexual activity, but because of the lack of having to keep breaking. And that’s really all it was. I was there to get to know Peter. That was part of Peter.

Dr. Lilly was very excited by their progress. I’m not sure if he was one of the observers, but he fully supported Lovatt’s work with Peter and encouraged her to continue. Bateson, however, thought her experiments were failing and useless, and funders began to pull out (no pun intended). Ironically, the experiment didn’t end because of Peter’s intense libido, or “rambunctious” behavior as Lovatt called it. It ended because Dr. Lilly wanted to inject the dolphins with LSD to impress his backers. Peter’s life came to a tragic end, but not because of the LSD. He committed suicide after Lovatt left his life.

If any of that sounds intriguing, weird, or unbelievable to you, check out the documentary The Girl Who Talked to Dolphins for the full — true — story of Lovatt, Peter, Lilly, and LSD here: