via The Line Up

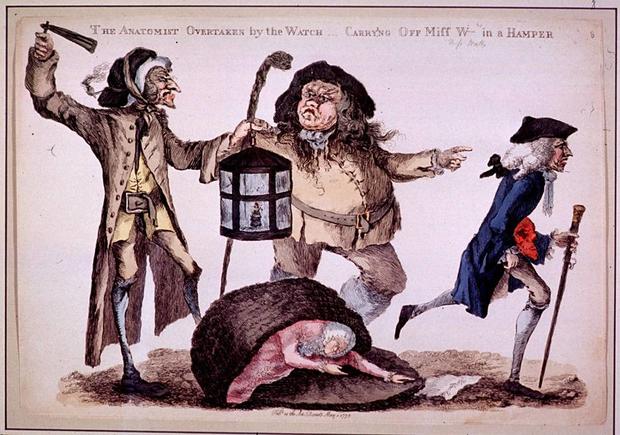

Although British anatomists often hunted for fresh cadavers in the 15th century, it was only in the 18th century that the demand for bodies boomed. An explosion of new medical schools and rising requirements for students meant that there were not enough bodies to go around. Enlightenment laws also only allowed for medical science to use the bodies of executed criminals. Soon enough, academics turned to illegal body snatching, which required skill in removing the body without taking the clothing or disturbing the ground too much.

From this need for human subjects, a lucrative and ethically questionable industry was born. Here are five grisly cases of body-snatching from the Victorian era.

1. Burke and Hare

William Burke and William Hare both emigrated from Northern Ireland to Scotland to work on the Union Canal. While Burke settled in Tanners Close with his second wife, Helen McDougal, Hare worked as an agricultural laborer before moving to Edinburgh in the mid-1820s. The two met in 1827 while working on the harvest at Midlothian, and they and their wives became fast friends. After Hare and his wife moved into Burke’s lodging house, the two soon plunged into the world of body snatching–only to become the world’s most infamous resurrectionist duo.

They first collaborated on selling the body of a deceased lodger to the desperate Dr. Robert Knox of Edinburgh Medical College. To meet Knox’s high standards, the pair turned to murder and killed 17 lodgers, prostitutes, and other unfortunates between 1827 and 1829. The West Port Murders shocked the medical science capital of Edinburgh. Luckily, Burke soon grew overconfident. On the night of October 31st, 1828, he used the pair’s trademark method of suffocation, later known as Burking, on a Mrs. Doherty after inviting her to his home. Too drunk to deliver her to Knox, Burke was found out in the morning and later executed by hanging thanks to Hare’s testimony against him. While Hare and Knox both escaped to England, Burke’s body was publicly dissected at the EMC and put on display as a skeleton, death mask, and wallet of his tanned skin.

2. Bishop, May, and Williams

Around the same time, John Bishop and his compatriots James May and Thomas Williams worked as resurrection men in London. After a dozen years of body-snatching, though, the trio decided to go from stealing corpses to making them. They specifically focused on street urchins, and made around nine guineas per body, which would translate to about $1,500 U.S. dollars today. At the same time, the ghouls boosted their profits by knocking out and selling teeth to dentists, too.

In November 1831, though, Bishop slipped up when preparing a subject for the anatomy instructors at King’s College. After he presented them with the corpse, the instructors noticed the boy’s suspicious head wound and called the authorities. When caught, Bishop and Williams confessed to the murders of a 10-year-old boy, a 14-year-old agricultural worker, and a 35-year-old woman. They admitted modeling their activities on Burke and Hare but threw their victims into a well head-first to die, after having been dosed with rum and laudanum. In his confession, Bishop declared with pride that he had sold as many as 1,000 anatomical subjects. Soon enough, though, he was just another anatomical subject, though his crimes inspired Charles Dickens to focus on the plight of beggar boys in his writings, especially The Pickwick Papers (1836).

3. Elizabeth Ross

In 1831, the body of Catherine Walsh of Whitechapel was sold to surgeons at the London Hospital. However, they quickly realized that the woman in question had been murdered. Walsh, who sold lace and cotton for a living, had been living with Elizabeth Ross and her family. Until that point, Elizabeth had largely been known for her love of gin and thieving. Upon investigation, though, Ross’ 12-year-old son and his father, Edward Cook, reported seeing the young mother with their lodger shortly before her death.

While Elizabeth was then accused of murdering Walsh and selling her body, she herself reported last seeing their lodger going off with Cook and her son. However, the damage was done, and rumors began to fly about neighborhood cats disappearing around the Ross home. In court, Elizabeth was portrayed as a large, burly Irish woman who could easily kill a man in cold blood. Yet, actual sketches showed a slight woman, and the son’s testimony seemed biased in favor of his father. Still, even despite little evidence, Elizabeth Ross was convicted and executed.

4. John Macintire

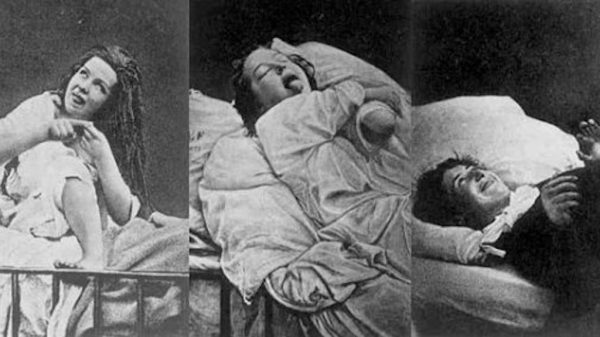

Not all encounters with resurrection men were negative. In a broadsheet from shortly before Burke and Hare’s spree, John Macintire describes a harrowing experience of being saved by grave robbers. The April 15, 1824 article starts at his deathbed, with the man mysteriously paralyzed but fully conscious. He watched in silence as his family gathered and then mourned over his coffin at his wake. Then, Macintire details what it was like to be sealed in his coffin, taken to the graveyard, and buried, with clods of dirt falling onto his wooden prison.

Silence fell, and Macintire was left to the ensuing darkness. As he imagined his ensuing death, the man heard the sound of digging. A gang of body-snatchers pulled him from the grave, stripped him of his shroud, and delivered him to a local university. There, he was laid out on a dissection table as students and doctors alike filled the room. Macintire realized he was in a lecture hall shortly before he felt the knife slicing his chest and finally woke. Once the doctors realized their corpse was not dead, they were able to fully revive him, and the man recovered.

5. The Boiling of Bones

Ross, Bishop, Burke, and Hare’s crimes all led to the 1832 Anatomy Act, which combatted body-snatching by increasing the supply for medical research. Yet, decades later in 1885, a similarly gruesome crime was uncovered in San Francisco, California. After complaints of a stench from a building in Chinatown, the city’s coroner uncovered decomposing human remains in the basement.

In one room, workers were busily boiling the bodies down, scraping the flesh off in order to speed the process. Most bodies had been taken from California area cemeteries, likely on behalf of their family members back home in China. They had paid for their late loved ones’ bodies to be boiled down to the bones so that they could be easily shipped back home. By the end of their investigation, authorities had recovered over 300 human bodies from the building’s basement.

Even during its heyday, body-snatching was an especially uncertain business. Not only were bodies not always legally obtained, but they could even be far from dead! This was the case for Robert Morgan, who was captured and tied up in a sack by hackney coachman and resurrection man John Bottomley in 1816. In other cases, the bodies of loved ones could be ransomed for cash. For instance, in 1881, the Earl of Crawford’s body was taken from his mausoleum in Aberdeen and held for ransom. Still, the profits of body-snatching were hard to resist, with an adult corpse in the early 1800s easily earning four pounds and four shillings or around 450 U.S. dollars today. As a result, even with increased regulation, the practice took quite some time to abate. To this day, people are often willing to steal other peoples’ bodies–so long as they can make a tidy profit in the process.