A brutal murder is reported in a quiet West Midlands village. Local authorities are unable to come up with a suspect or motive, so Scotland Yard sends its best detective to help crack the case. It could be the plotline to any number of classic English murder mysteries. However, the investigation into this particular homicide would soon take an unexpectedly strange turn. Hushed rumors of witchcraft, spectral black dogs, and ritual sacrifice would surround the case as it became entangled in the dark folklore and history of the region. Was this the work of a lone madman… or something far more sinister?

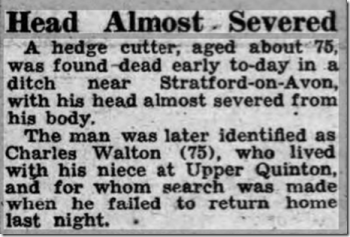

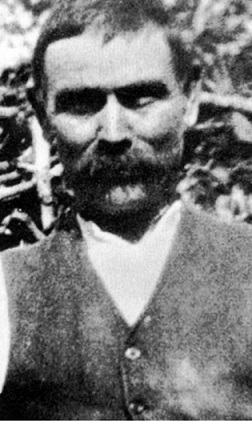

On the evening of February 14, 1945, in the small Warwickshire hamlet of Lower Quinton, the mutilated body of Charles Walton was discovered in a field he had worked just below Meon Hill. A lifelong resident of the area, the 74-year-old Walton was known to be a quiet man and something of a recluse. He shared a small cottage with his niece but otherwise spent most of his free time alone. Despite suffering from rheumatism he was physically active and earned his living as a farm laborer. By all accounts, he was described as honest, hard-working, and mild-mannered. Why would anyone want the old man dead?

Even more puzzling was the savage, and downright bizarre, nature of the crime.

Walton’s throat had been cut three times with his slash hook, a sickle-like tool that he used for hedging. The wounds were so deep that they nearly severed his head. He had also been brutally beaten, leaving his skull split, three ribs broken, and heavy bruising on his body. And as a gruesome final act, his pitchfork had been skewered through the lower part of his face. [1] This was done with such force that it left his corpse firmly pinned to the ground in what appeared to be a deliberate position, with the head forced back, almost as if to drain the body of blood. Some accounts further claim that a crude, cross-shaped symbol had been carved into his chest. [2]

With no immediate leads, it soon became apparent to the local authorities that outside assistance would be needed. Detective Chief Inspector Robert Fabian, the foremost police detective of his day, and his partner Albert Webb were soon dispatched by Scotland Yard and tasked with bringing Walton’s killer – or killers – to justice.

THE OCCULT CONNECTION

Lower Quinton is a small rural village with a population of a few hundred. In reality, it is no more than a village green surrounded by some old thatched-roofed cottages, a church, a local pub, and some outlying farms. Surely someone would know something about the murder.

To the surprise of the Chief Inspector, not a single person came forward with any information. He and his partner personally interviewed nearly five hundred residents from the Lower Quinton area during their investigation, only to be left with more questions than answers. “There were lowered eyes, reluctance to speak except for talk of bad crops – a heifer that died in a ditch,” Fabian noted. “But what had that to do with Charles Walton? Nobody would say.” [3] Even more baffling, no one seemed to fear for their safety. An elderly member of this small community had been violently butchered in broad daylight and there was little concern of a madman on the loose.

Whether frightened, suspicious of outsiders, or bound by some oath of secrecy, Fabian was convinced that the residents of Lower Quinton were hiding something. [4] Left frustrated by his interviews and with few clues that could help bring light to the case, he began to look into both the personal life of Charles Walton and the history of this peculiar region.

To better acquaint him with “the ways” known to the people of rural Warwickshire, Fabian was given a book entitled Folklore, Old Customs and Superstitions in Shakespeare Land, authored by a local clergyman named J. Harvey Bloom in 1929. [5] The book chronicles various folk stories and superstitions unique to the region, many of which seem to tap into a broader sense of darkness that permeates the area. For centuries, the county was known to be a hotbed of witchcraft and paranormal activity, and, to some degree, continued to be steeped in these beliefs at the time of the Walton murder.

Given the unusual, almost ritualistic, nature of the killing, Fabian began to consider the possibility that witchcraft had some role to play. He also openly wondered if there might be a broader conspiracy at work in the village. The theory seemed far-fetched at first, but there were certain details that would continue to point the case in this direction – including the background of Charles Walton himself. From what little information locals offered up, a curious assessment of his character started to emerge. Most described him as an eccentric and solitary old man. However, there were some who spoke of him in a fearful way and claimed that he possessed “certain powers.”

It was said that the old man was gifted with a unique ability to communicate with animals. As a young man, Walton was alleged to have been an accomplished “horse whisperer” – someone able to control horses through hand or eye motions. He could also speak with birds. According to one witness account, “Walton had been seen on many occasions imitating the songs of the nightingale and chirping to other species of bird. He openly professed to be conversant in the Aeolian language of his feathered friends, for they seemed to obey his requests to refrain from eating the seeds sown in the fields of his little plot.” [6]

There was also talk of Walton being a clairvoyant and seer of spirits. Interestingly, a childhood example of this “second sight” is documented in Bloom’s book of local folklore. He wrote of “a plough lad named Charles Walton [who] met a black dog on his way home nine times in successive evenings. On the ninth encounter, a headless lady rustled past him in a silk dress, and on the next day he heard of his sister’s death.” [7] This paranormal encounter “stained Walton’s soul” according to his superstitious-minded neighbors, imbuing the already strangely gifted child with even darker powers such as “the evil eye” – the ability to place a curse through the hypnotic gaze. Some villagers even came to believe that he was a witch.

If true, this might explain the toads.

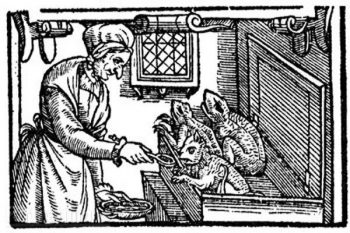

During a search of the Walton residence following the murder, it was discovered that the back garden was overrun with large Natterjack toads. Rumor had it that the old man was breeding the creatures for nefarious purposes. The Natterjack, or walking toad, figures prominently in the annals of British witchcraft. In fact, during the sixteenth century, they were even collected and burned as “familiars of witches” and “emissaries of the Evil One.” [8]

Among a witch’s spell-casting arsenal was the practice of “blasting” – the power “to interfere with or destroy the fertility of man, beast and crop” – which, in some cases, saw the use of Natterjack toads. When the infamous Scottish witch Isobel Gowdie went on trial in 1662, she confessed to, among other crimes, fastening small plows to her toads and setting them loose in the local fields, leaving the soil sterile and unable to produce crops. [9]

Despite decent weather, the region’s crop season had been exceptionally bad the year prior to the Walton murder. People even complained that the beer brewed from that wheat harvest was bitter and undrinkable. Lower Quinton was hit especially hard and a few villagers alluded to the possibility that Charles Walton may have blighted the crops through witchcraft. One of Walton’s former employers, a farmer from nearby Long Compton, may have actually witnessed the blasting ritual firsthand. “Old Charlie,” he claimed, “used to catch a toad and tie a toy plough to its legs and have it run along towing the thing across a field.” [10]

Behind the wall of silence encountered by the Chief Inspector, were there area residents who believed that Charles Walton had hexed the land and sickened livestock with his bewitched toads and powers of the evil eye? Could he have been the victim of some brutal form of folk justice carried over from the area’s past witch-hunting traditions? According to the official case files, there was no direct occult connection. However, off the record, Fabian believed this to be a real possibility.

A LAND OF DARK ENCHANTMENT

The Cotswolds region, and the county of Warwickshire in particular, has been steeped in a strong belief of the supernatural since its earliest days of settlement. The brooding rural landscape has always provided fertile ground for tales involving witches, phantom coaches, headless horsemen, a ghostly woman in white, mysterious black dogs, faeries, and various demonic entities. It’s also a region where the outdated folk beliefs and traditions long since discarded elsewhere in Britain have persisted.

In his memoirs, Robert Fabian incorporates local legend into his description of the Walton crime scene. “On the hilltops around Lower Quinton,” he wrote, “are circles of stones where witches are reputed to hold Sabbaths, and it was under the shadow of Meon Hill, not far from the stone circle of whispering knights, that on Valentine’s Day of 1945 a rheumatic old man was found murdered.” [11]

Meon Hill, a circular mound at the edge of the Cotswold ridge, is located in an area dotted with Neolithic and Bronze Age burial mounds and the remnants of various Iron Age and Roman encampments. From the time of these ancient inhabitants, and throughout the ages since, the entire area has been associated with dark, supernatural forces – an evil place, where even the birds won’t sing. Some say it’s a gateway to Hell. [12]

The Celts believed the hill was the resting place of Arawn, lord of the underworld. [13] Accompanied by a pack of spectral hounds, Arawn would embark on nightly hunts to gather the souls of the departed. Night travel could be a dangerous venture in Old Britain, as a hapless encounter with Arawn’s nocturnal hunting party was considered a death-omen. [14]

In later times, the Devil would take up residence at Meon Hill, using it as his earthly base to launch attacks against the newly established Christian population. Enraged by the construction of nearby Evesham Abbey in the eighth-century, local legend describes how the Devil kicked a massive boulder down the hill in an attempt to destroy it. However, as the story goes, the village faithful managed to divert its course through the power of prayer. The boulder missed the Abbey and came to rest on Cleeve Hill, near Cheltenham, where the villagers carved it into a giant stone cross to ward off further attacks. [15]

Another devilish folktale took place in a nearby field called The Close, which stands on top of an ancient earthwork site of unknown origin. Drawing a circle on the ground and reciting the Lord’s Prayer backward, a young man from Long Compton signed a pact with the Devil. In return for his soul, the man was given twelve imps as his own personal servants. He would later cause a scandal at Banbury Fair when he summoned a demonic spirit that appeared in the shape of a black rooster. [16]

The “stone circle of whispering knights” mentioned in Fabian’s memoirs refers to a section of the ancient megalith site known as The Rollright Stones, located a few miles from Meon Hill, which dates back as early as 2,500 BCE. Three separate elements make up the site – The King’s Men, a circle of seventy-seven large stones that was built for ceremonial purposes; The King’s Stone, a single monolith that stands to the north of The King’s Men; and The Whispering Knights, which lie to the east, are five upright stones that lay inwards towards each other as if they were whispering behind the king’s back. [17]

According to legend, The Rollright Stones are the cursed remains of a Viking king and his army. While marching through the Cotswolds, the king, intent on conquering all of England, had run afoul of a local witch named Mother Shipton. The angered witch – who, in some versions of the story, is portrayed as a representation of Sovereignty, the goddess protector of the land – transformed the invading army into stones and herself into a nearby elder tree that eternally guards over them. [18] The curse is briefly lifted on certain nights of the year when, at the stroke of midnight, the stones come to life. Some of the king’s men leave their place on the hill to drink at a nearby spring, while others join hands and dance. In some versions, the faerie folk who dwell in caves underneath the stone circle come out to join in the late-night festivities. [19]

The Rollright Stones are believed to be charged with supernatural energy, and a special significance is placed on the King’s Stone. Regarded as a potent phallic symbol, imbued with the power of fertility, tradition has it that if a local woman is unable to conceive after marriage, she visits the site on a full-moon night and rubs her naked breasts against the King’s Stone – always resulting in a healthy baby nine months later. [20]

The ancient stone circle has also traditionally provided a place of gathering for witches. In the sixteenth century, a witch-hunting commission was assembled in Oxford to investigate reports of coven activities at the site. A century later, “a witche” from Little Rollright was charged with attempted murder through black magic means. At her trial, she was accused of having attended sabbats at the Rollright Stones and Boar Hill (outside of Oxford) and sentenced to hang. [21] It is even claimed that as a child, Charles Walton would “steal out to the mysterious Rollright Stones nearby and watch witch rituals.” [22]

Recently, in August 2015, the 1,400-year-old skeletal remains of a Saxon woman were unearthed near the stone circle. She was found buried with a large amber bead, an amethyst set in silver, copper pins, a spinning wheel, a decorated antler, and a patera – a ladle-like ritual instrument used to make burnt offerings to the gods. Based on these items, experts believe her to be a woman of high spiritual status, or else a witch – Mother Shipton?. [23]

BLACK DOG CURSE

Arawn’s night hunts may have faded with Britain’s pagan past, and it would seem that the Devil has kept a much lower profile in recent years, but an unspoken dark presence still surrounds Meon Hill. Likewise, ritual activity continues at the nearby Rollright Stones. Gatherings of cloaked figures, mutilated animal remains and evidence of nightly bonfires have all been reported at the site. However, as far as lingering local legends go, it’s the black dogs that residents fear most.

English folklore is full of tales involving phantom black dogs. Nearly every county has its own variant. Whether sighted along a lonely stretch of highway, the outlying hills surrounding a village, or lurking the local cemetery grounds, there are various theories as to what these spectral canines represent. Some say they are witches’ familiars or demonic entities, possibly a manifestation of the Devil himself. Others identify them as the ghosts of murdered or executed individuals who haunt the area of their demise. Regardless of the paranormal back story, popular superstition casts them as cursed entities – the black harbingers of death and misfortune. [24]

Black dogs would feature prominently in the Walton murder case. As already mentioned, a young Charles Walton was haunted by a black dog in the days leading up to his sister’s death. A lifetime later, during the investigation into his murder, another mysterious black dog encounter would take place.

While he was in Lower Quinton, Chief Inspector Robert Fabian’s investigation would bring him through St. Swithin’s Cemetery and into the fields surrounding Meon Hill. On a nearby stone wall, he noticed a peculiar black dog following his movements. A moment later it was gone. When he left the field, a boy was walking nearby. Fabian asked him if he was looking for his dog. The boy seemed confused, so he specified (“the black dog…”). On hearing this, the boy turned pale and fled in a panic. Word soon spread throughout the village that the Chief Inspector had seen “The Ghost.” [25]

A series of strange incidents would happen in the days following this phantom black dog encounter.

The next morning began with the discovery that another cow had dropped dead in one of the grazing fields around Meon Hill. Never a good way to start a day. Later that day, as Fabian attempted to conduct more interviews, he noted that the entire atmosphere of Lower Quinton had changed. In his memoirs he writes, “when we walked into the village pub that evening silence fell like a physical blow. Cottage doors shut in our faces, and even the most innocent witnesses seemed unable to meet our eyes. Some became ill after we spoke to them.” [26]

A few days later, a black dog was found dead and hanging from a tree near the spot where Charles Walton’s body had been discovered weeks earlier. This was likely a sick prank played on Fabian by some locals following the news of his sighting. However, it may have been a warning. It was at this point in the investigation, Fabian would later write, “[that we] realized for certain that we were up against witchcraft.” [27]

A SOIL THAT THIRSTS FOR BLOOD

A popular theory is that Charles Walton’s murder was some form of ritual sacrifice – “the ghastly climax of a pagan rite,” according to the Chief Inspector. [28] Margaret Murray, a professor from University College in London who had written extensively on the history of European witchcraft, took a great interest in the Walton case. She claimed that the murder was likely a ritual act, performed for the purpose of replenishing the soil with the old man’s blood. “The belief is,” according to Murray, “that if life is taken out of the ground […] it must be replaced by a blood sacrifice.” [29]

Not much is known about “the old ways” as they were practiced during Iron Age Britain. What little information there is has been pieced together from the accounts of Roman historians and various archaeological discoveries – both of which point to the importance of ritual sacrifice within the ancient Celtic magico-religious system.

Sacrifice was the means by which the balance of nature was maintained, with offerings made to the governing divine forces in exchange for their blessings. Most consisted of animals, food, wine, incense, weapons, or jewelry. However, the ritual murder of humans was not unusual. It was an extraordinary form of sacrifice made during particularly critical times; to avert a famine or epidemic, provide victory before a battle, promote fertility, or guarantee a successful harvest. [30]

Victims would be selected from across a wide spectrum of candidates that included criminals, kings, menopausal women, adolescents, rival clan chiefs, social outcasts, and witches. [31] Witches in particular are thought to have been a sacrificial favorite. As it was widely believed that they possessed the power to disrupt or manipulate the natural order, a witch provided the ideal scapegoat offering to appease the gods and restore essential balance.

Celtic Druids are most infamously known for burning people in large wicker effigies. But they also strangled, drowned, poisoned, stoned, beheaded, dismembered, and buried them alive. The sacrificial act could vary, with different means of dispatching used for different ceremonial purposes – and sometimes the gods called for a bloodbath. One particularly gruesome Druidic ritual shares certain similarities with the Walton murder. Known as “the threefold death,” multiple killing methods (such as strangulation, head injuries, and throat-cutting) would be used in an act of ritual overkill to either appease multiple gods or ensure maximum bloodshed. [32]

As an agriculturally-based society, blood was particularly important to the Celts when it came to maintaining a healthy crop cycle. During the winter months, when the land had frosted over and the sun hung low in the sky, it was believed that the world had reached the end of its life-cycle. In order to “reawaken the earth” and usher in a new season of rebirth and revitalization, the soil needed to be symbolically replenished with life-giving blood. [33]

If the Walton murder was indeed some crude form of human sacrifice, the date when it took place may hold some significance. He was killed on February 14th. Going by the old (pre-Gregorian) calendar, which was twelve days behind, this date would correspond with the Celtic Midwinter festival of Imbolc. As a celebration of new life, Imbolc rituals centered around ensuring a successful growing season and the health and fertility of local livestock. [34] If rumors are to be believed, Walton was to blame for the failure of the previous year’s harvest and the unexplained death of a cow. To break the hex he was believed to have placed over the community and restore a sense of natural order, it may be no coincidence that his blood was spilled on this day.

The use of a pitchfork may further reinforce the ‘ritual murder theory,’ and is also not without precedent in the region. Following the Anglo-Saxon settlement of the area in the fifth-century, new traditions of witch-hunting would take root. Differing from later medieval Christian beliefs, the Anglo-Saxon concept of witchcraft centered on specific acts of (perceived) sorcery, rather than some broader diabolical conspiracy. The practice itself was not considered a crime; however, if it were used for criminal purposes, the punishment could be harsh. One crude investigative method used was called stacung (“sticking” or “staking”), where the bodies of the accused would be pierced with iron spikes, pins, or large thorns. If the wounds festered and turned black, it was considered proof that they were practitioners of black magic. [35]

Similar to the original stacung practice is a more recent (beginning in the 1500s) Cotswold hill-country belief that a witch’s powers could be drained through “blooding” – that is, to draw blood by a non-lethal stab wound (“be it but a pin’s prick”). William Shakespeare, the area’s most famous native son, even made reference to the practice in his play Henry VI, Part I (“Blood will I draw on thee, thou art a witch.”). [36] A number of blood-letting assaults against suspected witches would take place in the Warwickshire village of Tysoe in the later nineteenth-century. In one such attack, an elderly woman was seized by area residents, who used a corking pin to puncture her hand in an attempt “to nullify the effects of the evil eye she had cast upon them.” [37]

KILL THE WITCH

As with most murder mysteries, the facts surrounding the Charles Walton case would become murky and sensationalized over time – admittedly, even some of the “evidence” presented in this article is based on unsubstantiated rumor or secondary sources. One controversial detail is the claim made that he was found with a cross symbol carved into his chest.

If true, this would be strong support for the claim that it was a witch-killing. For centuries, Christian folk superstition has held to the belief that ‘the sign of the cross’ could be used as divine protection against malevolent forces or spell-casting, particularly in defending against “the evil eye.” During Warwickshire’s witch-hunting past, a more overtly religious form of “blooding” involved carving a cross directly onto the body of a witch in order to nullify their diabolical powers (or else ensure that a dead witch could not return from the grave). [38]

The problem is that none of the official police reports, autopsy documents, or contemporary newspaper accounts mention a cross being carved on Walton’s body. [39] So how did this detail enter into the popular mythos surrounding the case? It may have started as a local rumor. But more likely it is based on a previous area murder that shares eerily similar characteristics to, and has since become intertwined with, the killing of Charles Walton.

Seventy-five years prior, in the neighboring village of Long Compton, an elderly woman named Anne Tennant (some accounts name her as Ann Turner) was attacked and killed with a pitchfork by a mentally unstable farmhand named James Haywood. According to court records, Haywood believed Tennant was one of sixteen witches who lived in the village, that she possessed the power of the Evil Eye, and that she had “bewitched the cattle and land of local farmers.” More directly personal, he also blamed her spell-casting for a death in his family and severe cramping that prevented him from working in the fields. [40]

Haywood defended his actions to the court, explaining how he felt it to be his duty to protect the community from Tennant’s black magic. “It’s she who brings the floods and drought,” he argued. “Her spells withered the crops in the field. Her curse drove my father to an early grave!” The excited man detailed how he “pinned her to the ground with a pitchfork before slashing her chest with a billhook in the form of a cross.” [41]

To prove the righteousness of his cause, he insisted that the judge dig up the old woman’s corpse and “weigh it against a Church bible” to confirm that she was indeed “a proper witch.” [42] The judge declined this request and instead charged Haywood with manslaughter. He was later found to be criminally insane and lived out his remaining days at the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum.

Although James Haywood was ruled to be a man who suffered from delusions, his belief in witches was in fact shared by many people in the community. Reporting on the trial at the time, one London newspaper would note, “there is [still] a general belief in witchcraft at Long Compton and in other villages of South Warwickshire, among a certain class of the agricultural population.” [43]

Years later, just prior to the Walton murder, these regional folk beliefs would once again enter the media spotlight when another seemingly occult-related killing was discovered in nearby Worcestershire.

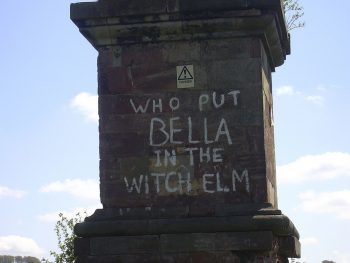

On April 18, 1943, four boys were walking through the forest near Wychbury Hill when, to their horror, they discovered a skeleton staring at them from inside a tree hollow. They reported their grisly finding to their parents, who immediately alerted the authorities. Police determined that the remains were of a female and the cause of death was concluded to be “likely suffocation.” Judging by the decomposition, it was estimated that the murder had taken place eighteen months prior, and it was obvious that someone went through a lot of trouble to place the corpse in the tree. A severed hand from the body was also discovered buried in the ground nearby. [44]

Dental records failed to reveal the identity of the woman, and there were no local missing persons who fit her description. Police were at a loss. With a considerable passage of time since the murder had taken place and the limited resources available during wartime Britain, the ‘Tree Riddle Murder’ case soon went cold. It was at this time that cryptic graffiti began appearing around the West Midlands – “Who Put Bella in the Witch Elm?” Detectives involved with the case believed that the chalked messages, carefully written in three-inch-deep capital letters, were all written by the same hand. Whether this was the killer taunting police or someone who knew the victim is anyone’s guess. [45]

There are many theories regarding the true identity of “Bella” and the details surrounding the case. But given the region’s history, it came as no surprise when the rumors of black magic began to circulate. Margaret Murray, who would later be consulted during the Walton investigation, speculated that perhaps “Bella” had run afoul of a local witches’ coven and was ritually murdered. “The cult of tree worship is an ancient one and is linked with sacrifices,” Murray would explain to news reporters eager to make sense of the crime. She also believed that the buried hand may have had some ritual significance. [46]

Ultimately, it will never be known who put Bella in the Witch Elm, or why. The case was officially closed in 2009. Curiously, when the files were donated to the Worcestershire county archives, it was discovered that the woman’s remains had gone missing. After an initial examination by James Webster, a forensic expert from the University of Birmingham, they simply disappeared from record in 1943. This has led some people to believe there may have been an official cover-up. [47] Regardless, without the help of modern DNA testing, both the woman’s identity and any possible explanation for the strange murder remains a mystery.

CONCLUSION

So, was Charles Walton “England’s last witch-killing,” as many have claimed? We will never know for sure. Like ‘Witch Elm Bella’, Walton’s killer (or killers) and the motive behind the grisly murder would never come to light. Initially, there was some suspicion placed on his employer, a farmer named Alfred Potter, who owned the land where the murder had taken place, but he was soon cleared. Further rounds of questioning also provided no new information – before slamming his door on the detectives, one elderly villager shouted: “He’s been dead and buried a month now, what are you worrying about?” [48]

The Walton case would be Chief Inspector Robert Fabian’s single unsolved murder throughout his long career with Scotland Yard. “Maybe somebody in that tranquil village off the main road knows who killed Charles Walton,” lamented Fabian. “Maybe one day somebody will talk? Not to me, a stranger from London, perhaps – but I happen to know that in the offices of Warwickshire Constabulary the case is not yet closed.” [49] No one ever has. It’s a mystery that still lingers on after seventy years, and to this day the case continues to be the oldest unsolved case on record with the Warwickshire police.

In one final mystery, Charles Walton’s corpse would also eventually go missing. It’s known that he had been buried in St. Swithin’s Cemetery, in the churchyard directly across the road from his cottage and a short walk from the field where his mangled body was found. But there is no longer a gravestone that bears his name and no one can seem to remember exactly where the plot was located. It is assumed that the villagers of Lower Quinton had become tired of being associated with the infamous “occult murder” and removed the marker to discourage bothersome legend-trippers from disrupting the peace of the cemetery grounds. They could also have been lost during some churchyard renovations that happened fifty years after his death. Or else his remains may have been removed altogether and transferred to some unknown location. [50]

With no surviving family, Charles Walton’s memory will simply live on as another dark chapter in the annals of Warwickshire legend and folklore, and whoever spilled his blood on that fateful February day will remain forever lost to the shadows of history.

Mark Laskey

http://illuminating-shadows.blogspot.com

——–

FOOTNOTES

1. Simon Read, The Case That Foiled Fabian: Murder and Witchcraft in Rural England (Gloucestershire: The HIstory Press, 2014), 17.

2. Anthony Masters, The Devil’s Dominion: The Complete Story of Hell and Satanism in the Modern World (Edison: Castle Books, 1978), 159.

3. Gerald Gardner, The Meaning of Witchcraft (Newburyport: Red Wheel Publishing, 2004), 235.

4. Read, 83.

5. Neil Mitchell, “The Pitchfork Murder: Is This England’s Creepiest Unsolved Crime,” Real Crime Daily, August 5, 2015.

6. Read, 159.

7. Gardner. 234.

8. Gary Varner, Creatures in the Mist: Little People, Wild Men and Spirit Beings Around the World (New York: Algora Publishing, 2007), 138.

9. Read, 160.

10. Read, 160.

11. Read, 50.

12. Rupert Matthews, Haunted Places of Warwickshire (Newbury: Countryside Books, 2005), 87-88.

13. Neil Mitchell, “The Pitchfork Murder: Is This England’s Creepiest Unsolved Crime?,” Real Crime Daily, August 5, 2015.

14. D. J. Conway, Magickal, Mystical Creatures: Invite Their Powers Into Your Life (Woodbury: Llewellyn Publications, 2001), 147.

15. Read, 11.

16. Michael Howard, “The Witches of Long Compton,” The Cauldron Online, 3.

17. Read, 50.

18. Read, 51.

19. Debra Kelly, “10 Legends of Ancient Megaliths and Stones From The British Isles,” Listverse, March 30, 2016.

20. Howard, 1.

21. Howard, 2.

22. Read, 51.

23. Mark Miller, “Skeleton of a High Status Spiritual Woman Unearthed Near Rollright Stones in England,” Ancient Origins Blog, August 9, 2015.

24. Bob Trubshaw, Explore Phantom Black Dogs (Marlborough: Heart of Albion Publishing, 2005).

25. Read, 127.

26. Read, 128.

27. Read, 127.

28. Read, 133.

29. Read, 160.

30. Miranda Aldhouse Green, “Human Sacrifice in Iron Age Britain,” British Archaeology, Issue 38, October 1998.

31. Ibid.

32. John Haywood, The Celts: Bronze Age to New Age (London: Routledge, 2004), 43.

33. Bob Curran, Mysterious Celtic Mythology in American Folklore (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 2010), 200.

34. Patricia Monaghan, The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore (New York: Checkmark Books, 2008), 256.

35. John Thrupp, The Anglo-Saxon Home: A History of the Domestic Institutions and Customs of England (London: British Library, Historical Print Editions, 2011), 271.

36. Gardner, 234.

37. George Morley, Shakespeare’s Greenwood: The Customs of the Country (Charleston: Nabu Press, 2010), 69.

38. Matthews, 87.

39. Read, 25-26.

40. Howard, 4.

41. Masters, 160.

42. Howard, 4.

43. “A Curious Murder Trial,” The Times, January 8, 1876.

44. Read, 135-36.

45. Strange Remains, “Who Put Bella Down The Wych Elm?,” Strange Remains Blog, April 24, 2015.

46. Read, 141.

47. Strange Remains, “Who Put Bella Down The Wych Elm?,” Strange Remains Blog, April 24, 2015.

48. Read, 128.

49. Devin McKinney, “Black Dogs on Meon Hill,” The Face At The Window, February 14, 2006.

50. Michael Watkins, The English: The Countryside and It’s People, (London: Elm Tree Books, 1981), 241.