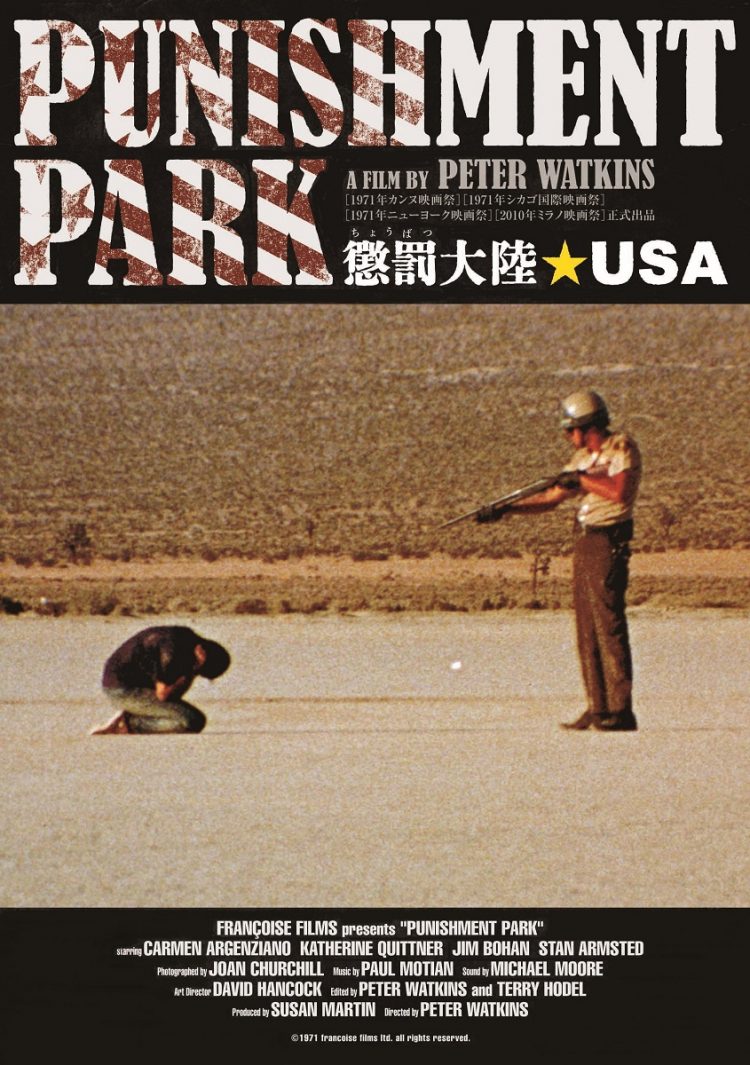

1950 and the US Govt passes the McCarran Internal Security Act, also known as the Subversive Activities Control Act. An Act that allowed the setting up of concentration camps for those accused or even contemplating subversion and dissonance within the US. It was this act in particular as well as the ever-growing social unrest, Nixon’s ‘secret’ bombing campaign on Cambodia, Kent University shootings, that led Peter Watkins to film 1970’s ‘Punishment Park,’ a film which viewed 50 years later is still prescient.

Punishment Park, filmed over three weeks, is a fictional narrative in the documentary style. Set in the searing heat of the “Bear Mountain National Punishment Park”, more commonly known as the San Bernadino desert, we follow two groups of accused dissidents, Group 638 and Group 637.

The film starts as Group 638 is driven to a military tent in the Southern Californian desert. Accused of such crimes as writing seditious lyrics, they stand in front of a biased tribunal. Upon sentencing, towards the end of the film, Group 638 is given two options. 1, serve a minimum of 15-20 years in prison, or 2, choose to enter Punishment Park. A 53 mile or three-day trek across open arid land where upon reaching a Stars and Stripes flag, freedom will be granted, if however, caught, they are set to serve the remainder of their sentence.

It is this chance for possible freedom where we follow the second group. Sentenced to spending three days in Punishment Park Group 637 are released two hours ahead of the national guard and cops who, of course, are armed to the teeth and have vehicles. The sound of screaming jets overhead, the chugging thunder of helicopters, and the distant echo of gunfire along with the ominous and at times monosyllabic percussion of artist Paul Motian adds to a tense desert escape. Filmed in a handheld style, we follow the group through the lens of a small foreign news broadcaster.

Punishment Park didn’t rely on scripts, each actor created their backstory, and all dialogue was improvised, thus adding spontaneity to the scenes. It’s this improvisation that’s pivotal to the film. For the trial scenes with Group 638 and the Tribunal Board, neither party of actors met before shooting. Instead, they were kept separated until the trial began where under the Californian heat, Group 638 were led into a windowless military tent where the accused Group, shackled and handcuffed, stood trial. The power of these courtroom scenes is both spellbinding and enraging.

Except for a handful of actors, most of the cast in Punishment Park hadn’t acted before. The dissidents were chosen for their close physical resemblance to activists and songwriters such as Bobby Seale, LeRoi Jones, and Joan Baez. The tribunal members the same, the judge, in particular, bearing a close resemblance to Judge Julius Hoffman, the Judge who presided over the 1968 trial of The Chicago 7. Other members of the board, as well as some of the cops and National Guard, had ‘previous experience,’ the young upstarts were chosen for their physical resemblance and for their energy in expressing their own opinions and political convictions.

One group member in particular, Charles Robbins, played by actor Stan Armsted, gives a vitriolic and powerful performance, which in turn leads to him being bound and gagged in a none too dissimilar fashion used on Bobby Seale during the Chicago 8 trial.

Upon release, huge controversy surrounded Punishment Park, no company in Hollywood would touch it due to fear of interference from federal authorities. Peter Watkins was derided for creating an illusion, a psychodrama, of what the United States would look like under total fascist control. Critics called him a ‘delusional masochist,’ the film itself ‘a futuristic monster.’ Some people even believed ‘Punishment Park’ existed in real life, which says a lot about the film’s strength and realism. When Punishment Park first aired on Danish television in 1972, the Danish Press reacted in anger towards the US, not realizing that this perceived documentary was merely constructed fiction.

This approach, this blurring of lines between fiction and non-fiction, is what makes Punishment Park such an exciting film. Soon after the release of Punishment Park, The McCarran Internal Security Act was repealed; however towards the end of 1971, under Richard Nixon, 13,000 political prisoners were still incarcerated. Even today, concentration camps within the US do exist; we only have to look to the many inhumane ICE detention centers to see this is blatantly obvious. In 2004, post 9-11 and post-Patriot Act, Peter Watkins himself said, “Punishment Park was a film about tomorrow, yesterday or five years from now,” an outlook and a reality that we are all living today, we are in the constructed fiction of Peter Watkins.

– Howard Matil