by DARIEN CAVANAUGH via Defiant

When alt-right poster boy Richard Spencer’s face ended up on the receiving end of the punch memed around the world on Inauguration Day, it raised questions among liberals and leftists about the role of violence in politics.

The debate quickly intensified following reports that an anti-fascist protestor was shot at the University of Washington as Breitbart editor Milo Yiannopoulos gave a speech there on the night of the inauguration. Then on Feb. 1, 2017, violent protests at the University of California Berkley shut down a scheduled appearance by Yiannopoulos.

The recent discussions of political violence, particularly as it relates to punching neo-Nazis, tend to center on ethical concerns and skepticism over whether or not it’s an effective tactic.

I’m not going to attempt to address the ethical question. There are reasonable arguments for both nonviolence and the use of force.

But I will say this — punching Nazis is absolutely an effective tactic. In fact, it’s been proved time and time again to be the most effective means of simply communicating with Nazis.

this is as patriotic as I’ve felt in a long time pic.twitter.com/yiVxd8semM

— young stalin(parody) (@prttybadtweeter) January 21, 2017

Violence between anti-fascist and neo-Nazis is nothing new. It’s been getting more attention since the rise of the alt-right and Pres. Donald Trump’s inauguration, but it’s been going on for decades.

Recent incidents include anti-fascist protest at a white supremacist rally in Sacramento in 2016. Several people were beaten and stabbed at the rally. Likewise, protestors at a November 2016 conference for the National Policy Institute, which Spencer heads, attacked one attendee and harassed several others.

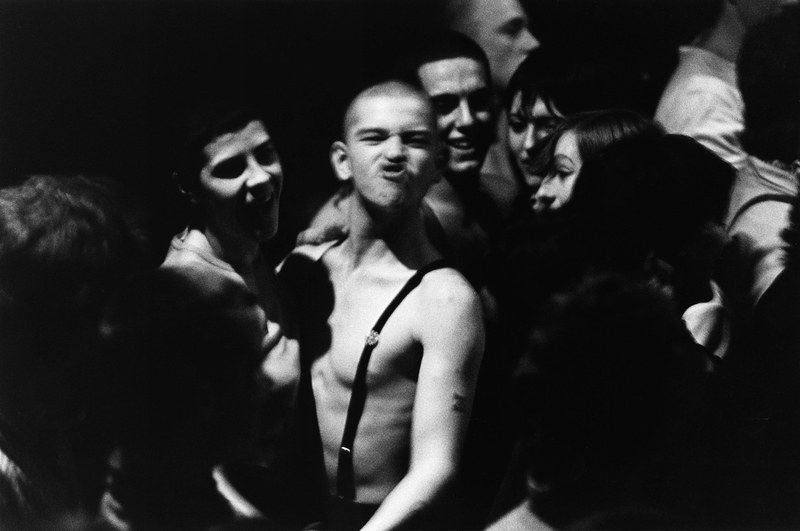

In the 1980s and ’90s, much of the violence between anti-fascists and neo-Nazis occurred in the hardcore and punk music scenes.

I started listening to metal, punk and hardcore when I was 12 years old in 1988. The first show I ever went to was DRI, Sick of It All and Nasty Savage at the Cuban Club in Tampa on March 3, 1990. I was 13 at the time.

That night, there were several hundred people, maybe a thousand, in the enclosed courtyard behind the club where the bands played. Most of the people at the show were metal heads there to see DRI and Nasty Savage, but around 50 neo-Nazi skinheads were also there to see Sick of It All.

Vicious fights broke out almost as soon as the music started.

The skinheads targeted random metal-heads for no reason — just picked one or two of them out of the crowd, isolated them and ganged up on them. Any time one of the metal-heads dropped to the ground, they were immediately swarmed by a bunch of skins who kicked and stomped them.

Eventually several police cars and a few ambulances showed up and things calmed down for the rest of the night.

It was a terrifying introduction to the hardcore/punk scene, especially since I was a scrawny teen with long hair and was probably wearing a sleeveless Sacred Reich shirt. I looked like a metal-head, and Nazi skinheads have no qualms about beating up kids.

Spread the word around. pic.twitter.com/pacj1K7Xl3

— Peter Nygaard (@RetepAdam) January 21, 2017

Several months later, my friends and I witnessed a similar situation unfold at a Social Distortion and Gang Green show at Jannus Landing in St. Petersburg, Florida. And in July 1990, six skinheads attacked an old homeless black man who wondered into a Judge show at the Star Club in Ybor City during the Bringing It Down tour.

I had just turned 14. I was still scared of everything. But when some older guys started breaking up the fight and ushering the man out the back door to safety, a couple of friends and I timidly helped them, basically by trying to clumsily stand between the man and the skinheads so they couldn’t get to him.

It was a frightening moment. But I think it also made us realize the skinheads weren’t as tough as we had thought they were. There was something about seeing these guys, who were all in their 20s, 30s and 40s, attacking a helpless old man that stirred something inside of us.

We didn’t start fighting the Nazis right away. For a while, we just helped other people break up fights — again, very timidly. I can’t recall when we quit just breaking up fights and started fighting, but we did.

Early on, most of us were kids. We were 14, 15 and 16 years old, throwing down with guys who were several years older than us. A lot of them were in their late teens or early 20s, but some of them were grown-ass men who had been fighting long enough to be fearless. Those were the truly intimidating ones.

There were rumors that years earlier some of the older skins had severely beaten a man and then killed him by setting him on fire as he lay battered in the street. One of them supposedly had a penchant for biting off people’s ears. There was one nicknamed Bam Bam who was known for dishing out knockout punches.

Several had stabbed people. There were other stories.

In other words, the skinheads we were fighting were often way bigger and stronger and meaner than we were, and we knew what would happen if they ever got us down or caught us alone. But we fought them anyway, and eventually linked up with a couple more of the older hardcore kids and a few SHARPS — Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice — who had been fighting them for years. New kids coming into the scene started joining in, too.

No Problem – Chance The Rapper (ft. Lil Wayne and 2 Chainz) pic.twitter.com/80t7vm6Rnq

— Alt-Right Getting (@PunchedToMusic) January 23, 2017

The scene still was not a safe space for anyone for some time. We knew we could be targeted on any given night if some Nazi skinhead decided he didn’t like the t-shirt one of us was wearing or if one of us looked at somebody the wrong way. People of color, women, members of the LGBT community or basically anyone who appeared vulnerable to the Nazis were at the greatest risk.

“Shows were fucking brutal for me as woman,” recalled Angela Art, who grew up in Tampa. “ I got groped, punched, and kicked all the time. I remember there always being skins at the Stone Lounge. Every damn show they’d be there fucking with people.”

Gerald Williams remembers being targeted by Nazi skinheads because of his race. “The Macabre show, I think, might have been the first show were I actually got fucked with or the first show where I really saw the skinhead presence,” Williams told Defiant.

“There were these five skinheads and one of them kept trying to start a circle pit but he would run into me in particular, five times in all,” Williams continued. “I remember after the third hit, Toby and Charlie ended up standing next to me because they noticed it too. After the fifth time, I remember turning around and he did the Nazi salute and Charlie punched him and we all started fighting.”

On another occasion Charlie got arrested after punching a skinhead in Ybor City and then chasing him down the street. The skinhead ran to a cop on patrol in the area for protection.

This was around 1993. By then we pretty much fought Nazi skinheads on sight. Charlie had seen a Nazi walking down the street, so he ran up and hit him. That’s what you did. It had become reflexive. The Nazis treated us the same way.

It was a bizarre sort of turf war. The skinheads had some loose hierarchy, but we never had any sort of organization or anything like that. We were just friends looking out for each other, and trying to help those in our community to do the same.

Jose and Ian, two Puerto Rican brothers, were the closest thing we had to leaders when it came to fighting Nazis. Those two were always at the front when things went down.

In those unsettling moments when a dozen or so of us would square off with a dozen or so Nazis, it felt a whole lot better if Jose and Ian were there. They were physically and personally unassuming, but they were also two of the best brawlers around.

“Ian never said shit, but man he could clear a room,” an old friend of theirs told me.

There were periods when we fought almost every time we went out, then the violence would ebb for weeks or even months at a time, usually because the skinheads grew tired of getting their asses kicked and stayed home for a while.

We lost sometimes — sometimes badly. In one brawl at the Ritz Theater, when I was around 16, I was beating on a skinhead my age when one of the older ones popped me with a quick one-two sucker-punch combo. One of the punches landed on the left side of my face and immediately clamped my eye shut. I couldn’t open it at all. It felt like the socket was packed with sand.

Read the full article on DEFIANT