via Dazed Digital

Dubbed Japan’s most-controversial photographer, Nobuyoshi Araki has, for nearly half a century, pushed the boundaries of respectability to near-buckling point – and beyond.

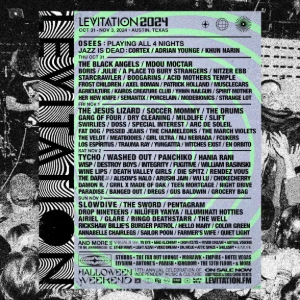

A new retrospective exhibition co-curated by Maggie Mustard and Mark Snyder at New York’s Museum of Sex celebrates the photographer’s body of work, a natural choice having spent a lifetime holding a mirror up to his nation’s complex relationship to sexuality and its censorship. Given the occasion, though, it could be easy to forget the very reason why this work is still so important.

Araki’s obsession for capturing unflinching erotic imagery that exists somewhere between the private and the public, the real and the imagined, could, in a post-Weinstein era, be pushed aside as no more than another male gaze on the female body. A reduction of a woman’s image to no more than an object to desire and obtain – if only one with the talent for capturing this abuse of power on film. But the very thing that makes this photographic master so interesting is that it’s much more complex than his simply being not just that. His work, and perhaps the man himself, is a cycle of constant contradiction in a world where the line between narrative and fiction is never clear.

It’s important for any honest reading of his work to acknowledge that Araki’s oeuvre exists at a point fairly late on a timeline of popular artists attempting to make sense of sexuality, and the uniquely Japanese understanding of what that means. More than his photographic contemporaries, Araki’s work is closely connected to a very different history, one of sex in art. From the shunga works of Katsushika Hokusai and Kitagawa Utamaro, masters of ukiyo-e, Japan’s (and arguably the world’s) first mass-produced media in the form of titillating woodblock prints, to film and literature by the likes of Ryu Murakami and Amy Yamada.

Rewind back to Japan’s Edo period (1603–1867) – which would become the Tokyo-centric modern Japanese culture we know – and society found itself in a very particular structure that goes a long way to explain this unique relationship to sex and sexuality. Where respect and respectability were key currency in the city, an ordered, socially conservative existence could happily continue because, just down the river was ukiyo (the ‘Floating World’), 18th and 19th century Edo’s pleasure district. Here, everyone from soldiers to foreign merchants and monks could engage in all manner of carnal pleasures, just out of sight.

This was no mere back-alley brothel quarter, though. What was on offer in ukiyo was as sophisticated in its set up as it was sordid. From the ethereal geishas to the drama of the kabuki theatre, this illicit playground inspired the hearts of anyone with an itch to scratch, even spawning its own tourist takeaway in the form of ukiyo-e (‘pictures of the floating world’). These woodcut prints of lurid scenes captured the chaos of what went on (and was the format that gave rise to the erotic art of shunga) – a more important ancestor to mass media as we know it than any western art history will have you believe, and a huge influence on arguably every aspect of Araki’s work.

Fast-forward to today and the lineage of this lurid world remains fairly intact, its descendants just slightly more neon-drenched than before. It is here during the mid 1980s that Araki, along with Akira Suei – the editor-in-chief of Photo Age, a magazine which had taken to handing over a generous portion of its pages each month to the photo-provocateur – would traverse the labyrinthine backstreets of Kabukichō, the city’s most notorious red-light district known rather romantically as the ‘sleepless town’.

for the full feature head to Dazed Digital