“Be who you needed when you were younger.” This quote by Ayesha Siddiqi is the first thing that comes to mind when I listen to Cockring’s grotesque and shimmering debut LP, Altar Call. This is an album for all the unhealed inner-children out there, all those dealing with feelings of trauma and alienation, all those weirdos and queer kids who can’t seem to find their tribe. In other words, Cockring is who we all need right now.

Brash, gritty, and inventive, Altar Call is not only musically compelling, but it is also intensely personal, fueled by vulnerability and vindictiveness. By pain and passion and piss.

With a true ear for compositional nuance, the musicians in Cockring know how to let a song breathe. Never resorting to a wall of sound to compensate for lack of creativity, they allow Cameron’s thudding, fuzzy bass to jab the listener in the solar plexus while Caleb’s drums dance and splash, complementing Jeff’s grooving and outlandish guitar riffs. Far from any of the boilerplate hardcore subgenres saturating the musical landscape right now, each piece on Altar Call feels truly ingenious, completely sincere, and itchingly catchy. With vocals that can capture the gut-felt rage of Antonio Marquez as easily as the disgruntled disillusionment of Raygun Busch and the incredulous anarchism of Delivan Oswood, vocalist Noah barks with an urgency and a righteousness that is extraordinarily rare in heavy music.

This music is moving, more than most hardcore dares to be. There is is a freedom to these songs that gives one the feeling of having been let loose after decades of containment. The emotional complexity and depth inherent to these tracks is no mystery once one explores the lyrical content of Altar Call.

An album with a coherent theme and arc similar to David Comes to Life or Crime and Punishment, Altar Call provides an intimate look at the lived experiences of Cockring’s members. Built on a narrative framework exploring the trauma experienced by queer youth in hyper-religious spaces, the album confronts themes of shame, betrayal, hypocrisy, and, most importantly, redemption. Through the specifity of their stories, the universal can be felt, as any thoughtful listener might contend with similar tensions between obedience and rebellion, between ugliness and beauty, between the sacred and the profane.

This work, as all good art, is emotionally demanding because it demands much of itself. Uncompromising in its raw musicality and in its subject matter, the listener, too, feels raw and spent by the albums end, only to feel equally drawn to spin it again to re-experience its catharsis.

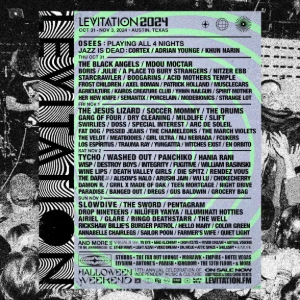

Cockring spoke generously to Cvlt Nation about their fantastic debut, Altar Call, which is out now on bandcamp and on No Time Records.

Cvlt Nation: I’d like to start by talking about the short journey from your demo to this Altar Call release. Can you share a bit about how you all came together, what made you kindred spirits, and what you think led to your rapid rise to being a well-loved band in under two years?

Noah: A story that comes up a lot—and it’s kind of funny—is how Caleb and I met Jeff. We were on a hookup app, and we ran into Jeff there. We were trying to get at him, you know? But it turned into something else. We ended up getting coffee and talking about music. During that conversation, we realized we had similar upbringings—not identical lives, but similar experiences with religion and identity. That connection brought us together.

It’s funny to think about, but when we decided to play music together, we were a bit cautious. Maybe it was catastrophic thinking, but we felt like we had to be on guard, like watching our backs. We weren’t sure how people would react to this kind of project. But especially in Sacramento, people really embraced us. The guys from Whole Hog, the people who run Cafe Colonial—they all welcomed us with open arms.

A lot of the fight we anticipated just didn’t happen. I think that fight energy got transferred into wanting to keep it going, keep making music, and enjoy the process. It’s been a much better time than we expected, and we’re just seeing it through and seeing what happens.

Cvlt Nation: It sounds like you were surprised by how little resistance you encountered. What do you think made the project more accepted than you anticipated?

Noah: For me, and I think for all of us, we’re a bit paranoid in general. Also, we’re all nearing our 30s, and when we got into punk and hardcore, it was a different scene. Personally, I never felt directly targeted, but there was this general sense of what was “safe” to talk about or express without having to defend yourself.

I think I carried that with me going forward. It’s one thing to attend a show, but playing one—especially for us since this is our first band, except for Jeff who played in a band in Japan—felt different. People always talk about how much the world has changed in the last 20 years, and I think that was the first time I really felt it. It is different now.

Jeff: Yeah, piggybacking on what Noah said, when we first got together, we were talking about pre-COVID shows, where things were way more intense. The mosh calls were rougher, and slurs like “faggot” were thrown around freely. Thankfully, things have changed. But Sacramento, for a while, was pretty intense. We wanted to create a band where people could feel comfortable being themselves, especially focusing on queer folks. We wanted to be a band for the outsiders, the outliers.

Cvlt Nation: It seems like the idea of being for the outsiders, outliers, and freaks is something punks have talked about for generations. But as you pointed out, toxic elements from the mainstream often infiltrate those spaces, and you find these punk environments increasingly resembling gym class, full of the same toxic masculinity punk has fought against for almost 50 years. Do you think this was especially true in California, or was it more of an issue before quarantine? What do you think caused the change?

Jeff: I’m personally surprised by the acceptance. I’m the eldest, and when I was in the hardcore scene, mosh pits were filled with people yelling slurs like, “Fuck you, faggots!” and “Fuck your God!” I always felt like I was in this weird in-between space. But now, it’s different. People are open to this kind of stuff. We wanted to bring the younger crowd in, and we did. The Sacramento scene has this amazing openness that really surprised me. I expected pushback, especially since 20 years ago things were so different. But the youth are queer, trans, and open, and that’s where it’s at now.

Cvlt Nation: As someone who works with youth and has helped create GSAs and queer spaces in schools for 15 years now, I’ve seen firsthand how hungry young people are for this. Not only are they accepting of it, they’re yearning for it. Back when I was involved in the scene, there were cities near me with this kind of thing, but it never made it to my neighborhood. It’s amazing how fortunate these kids are now to have it, and I think they recognize how special it is.

Noah: Yeah, I agree. We’re definitely not under the impression that we’re the first gay band or anything, but it does feel special. It’s something I’ve wanted to do since I was a teenager—not just make music, but be in a band that I wanted to see in my city when I was younger. There’s a lot of emotion in that for me. It feels like I’m putting my teenage self out there, like I’m giving something back to the universe.

When I started, I expected people to react negatively, like how it was when I was younger. I was ready for the same kind of weird vibe. But what we’re witnessing now is so different. It’s not like that anymore. Seeing that change was a full-circle moment for me. We started doing this for ourselves, but now I see kids at our shows, and I’m like, “Wow, this crowd looks so different than it did even five years ago.”

That’s been the best part—seeing everything change in real time. It’s not even just about your band, it’s like the universe is shifting.

Cvlt Nation: A friend of mine in a band once described being in the punk scene as being in “Neverland,” this sustained or suspended state of youth. That idea really stuck with me, especially as someone who works with youth. You mentioned the idea of being the band you needed when you were young, which connects with the concept of being the person you needed when you were younger. Bands like SSD were youth bands, part of the “youth crew,” and now many of them are in retirement, but that youth mentality is still so fresh. In the scenes I’m part of, they’re youth-run and youth-oriented, as they should be. What do you think is the role of a band like yours, or any band, when it comes to being for the youth or acting as role models in the scene?

Noah: What that brings to mind for me is how I grew up at odds with what the people around me wanted. I was raised in an evangelical family, with all that Southern Baptist craziness, so I felt like I had to rely on myself and create my own value system. But that’s tough to do alone. It wasn’t until I found hardcore and started meeting people that I became open to other ideas and could really develop my own values.

When I started going to shows in 2010 or 2011, bands like Punch and Loma Prieta from the Bay Area would do this thing where, between songs, they’d give these mini mission statements. It was the same thing every show, but it was important—stuff like “Be kind to your friends, be kind to strangers, care about animals, stop talking shit about homeless people.” That shaped how I interact with the world.

I think it’s important for hardcore to be driven by values and ethos. It can be cyclical—sometimes it’s not like that—but I think it’s almost cooler to stick to those values rather than regress to slurs and negativity in mosh pits.

Caleb: I think it’s important not only that we set a good example as elders, but also that we give younger people the resources and enthusiasm to keep the scene going. It’s one thing to put on shows and project the values we want to see spread, but that won’t last if the youth don’t keep participating. Like you said, this is a youth-driven thing. Kids need to want to start bands, go to punk flea markets, and respect the venues so they don’t get shut down. It’s about adapting to the privilege of being able to enjoy these scenes and keeping them alive. I hope that makes sense.

Cvlt Nation: Perfect sense, absolutely. In one interview I read, you made a distinction between punk and hardcore. Often in interviews, I use the terms “punk” and “hardcore” interchangeably, but you pointed out that you generally identify more as a punk band than a hardcore band. Can you unpack that?

Noah: Sure. I think that distinction comes from the experiences I had growing up. 10-15 years ago, there was more of a clear divide between punk and hardcore shows. At hardcore shows, I always felt more on edge, like I had to be on high alert. But at punk shows, it felt like nobody cared about that stuff. There’s a difference in energy for me when I think about punk versus hardcore from back then.

I don’t necessarily think it feels that different today, but I do think your entry point to hardcore influences that distinction. For example, we recently played a show with a beatdown band. Sound-wise, it was the kind of music that would’ve made me feel nervous in the past—like, I’d be looking over my shoulder. But then the band got on the mic and talked about trans rights and dedicated songs to people struggling with mental illness. It was just different from what I would’ve expected back then.

Jeff: Usually, beatdown is like, “kill everyone,” but that one band—we know exactly who we’re talking about—was so sweet. They were the hardest band, but they were like, “This is for your mental health. Let’s go!” It was so cute, and I was like, “Oh my God, this is the best band ever.”

Noah: Yeah, they were total sweethearts. And it’s not that stuff like that never happened before, but it wasn’t common. I think there’s been a bleed over from a general modern ethos that isn’t confined by genre or style anymore. It’s just not that black and white.

Caleb: I also think these labels are pretty fluid and subjective. One person might label a project as punk, while another might call it hardcore. They’re overlapping umbrellas, really. Ultimately, these labels exist to help us find music we like through comparison. I’m more comfortable letting others describe what we’re doing because everyone’s coming at it from different angles in terms of what they listen to and their experiences with music. For me, I’m so deep in it that I can’t accurately label what we’re doing. I think it’s subjective, and I’m open to hearing what others have to say about it rather than relying on my own monologue.

Cvlt Nation: Perfect. Noah, you mentioned your religious upbringing. I read through the zine you prepared for this release, and I really connected with it. I grew up in Catholic education from kindergarten through 12th grade, going to church multiple times a week. We weren’t allowed to start a GSA on campus, so we kind of started a pirate one in the hallway because we wanted to. The theme of religious trauma and hypocrisy seems to be a through-line in this album, especially in the lyrics on certain tracks. That kind of vulnerability is powerful. Can you talk a bit about how that became a focus for this work and how it’s influenced your songwriting approach?

Noah: Yeah, so I think it’s been there from the start. One of the things we all connected on originally was how Jeff, Caleb, and I all grew up in different forms of pretty extreme religion. Since I wrote the lyrics for the album, I wanted to give Jeff the opportunity to tell a story that a lot of people could relate to. And after reading the words Jeff wrote for that zine, I realized that even though our stories look different, it’s the same kind of hero’s journey.

The theme of religious turmoil really clicked for me when we were writing songs for our split with Fastcase. We wrote “The Cage,” and the lyrics just came out of me so easily. It hit me then that I was still carrying this weight with me. Over the past few years, I’ve also been experimenting with sobriety, going back and forth. Part of that journey has involved wrestling with concepts of a higher power, which led me to deconstruct my own history with spirituality and what that could look like for me now.

When we started writing the songs for this record, I asked myself, “What if I stayed in the church? What if I wrote an actual gospel record?” I thought, “What if these songs were like genuinely Christian metal?” Funny enough, I got into hardcore shows through catching Christian metalcore bands at a church in Sacramento, so I thought, “What if I had kept doing that?” This process has done a lot for my own spirituality—disconnecting from it, then reconnecting and recontextualizing it.

At the same time, I didn’t want the songs to be too specific to my personal experience. All four of us wrote our individual parts for this record, and I wanted to convey all of our collective experiences. That’s where I was coming from in writing this, and hopefully, that comes across.

The moment it really fell into place for me was when we were working on the song “Gospel.” It was originally going to be conceptually about giving up faith, and then I realized…

Noah: Yeah, I think “Gospel” started out as something that was going to be darker, almost like a rejection of faith. But then it morphed into this idea of rejecting a version of faith and finding my own. When I wrote it, it kind of hit me like, wow, it’s actually so sick that I’m queer. Like, by having this intrinsic part of myself, I get to meet people who share similar experiences, and that’s something powerful. At first, being queer felt like a deformity, but now it’s my faith. That’s where the song came together for me—like, I’m embracing my identity, and that’s where my faith lies now. It’s hard to explain, but that’s the essence of it. I’d actually be interested to hear what Jeff and Caleb have to say about it too.

Caleb: I think a lot of what Noah said resonates with me too. It’s like we all hang out together and share these experiences, so of course, we’re on the same page. For most of us, growing up in environments that were hostile to an intrinsic part of who we are—like being queer—that experience is always simmering just below the surface. So when we get the chance to express it, especially in something like music, it’s naturally going to come out. It’s part of who we are and what we’ve been through.

But what really strikes me is what Noah touched on—embracing spirituality. I remember this one band practice where Noah was super excited, almost with a wild look in his eye, talking about how we were now a Christian rock band. At first, I was shocked because my gut reaction was to pull away from anything spiritual or religious, given my background. But then it hit me: if punk has always been about rebellion, what’s more rebellious than rebelling against the rebellion? Instead of running from spirituality because it’s what you’re “supposed” to do, what if you actually confront it, inspect it, and form your own relationship with it?

For me, that embrace of spirituality is more punk than rejection because it’s terrifying. And moving toward something that scares you, instead of away from it, is one of the most powerful, empowering things you can do for yourself.

Cvlt Nation: I love that. It really resonates with the way drag often recontextualizes religious iconography. That experience of religious trauma for queer folks can manifest in ways that almost feel satirical or subversive, but deeper down, it’s part of a healing process. When you mentioned the hero’s journey, it made me think of that idea where you leave a place, find your way back, and then reinterpret what “home” means to you with all the new knowledge and understanding of yourself and the world around you.

For me, the track “Gospel” was pivotal. It’s the one where the album’s narrative arc really clicked. I thought I knew where the album was going, but then I realized it was more of a cyclical journey, a callback to where things started—but with this new sense of empowerment. There’s definitely something deeply therapeutic about that.

Noah: Yeah, writing this record really did feel like therapy, to be honest. I kept joking that going to band practice was like our weekly therapy session. But honestly, I wasn’t even joking that much.

Jeff: It’s true, though. Like every week, we were getting closer as a band, but also as people. We’d talk about our week, or life in general, and just say, “This is what I went through.” And because we know each other so well now, it felt therapeutic to channel that into the music. It’s almost like we were voicing each other’s traumas in some way. This is family now, whether anyone likes it or not.

Cvlt Nation: Not long ago, I had a conversation with a friend about how there just didn’t seem to be any good queercore bands anymore. We were like, “Do we really need queercore bands anymore?” because, honestly, what good band isn’t queer right now? This was in 2020, but it still holds true.

To Jeff’s point about youth culture, I think almost all young people today can identify with punk identity in some form. Because of that, the term “queercore” has become broader and less specific. It used to frustrate me because I’d search for bands like Limp Wrist and end up finding anything with openly queer members being labeled as queercore. I’m like, “This doesn’t sound like Limp Wrist at all!” I like most of those bands, but you can’t throw Pansy Division, Limp Wrist, Space Camp, and The B-52’s all into the same category and call them all queercore. Some of these bands are self-determined queercore, while others don’t really fit that mold. So, I’d love to hear your thoughts on this, especially about what it means to be a queercore band today.

Jeff: For me, I’m just so excited to see younger folks of all gender expressions coming to our shows and getting stoked about music. I always tell them, “Yo, start your own band!” I’ve even given out two guitars to young kids to encourage them. To me, that’s what really matters—if you’re a young kid starting a band, that’s fantastic!

Noah: Yeah, I think we all share that sentiment. Especially when we started this band, we felt like the term “queercore” was pretty much obsolete. It’s not necessary anymore, and that’s for the same reason you mentioned. It doesn’t help you find the music you want to listen to; it becomes more about who you are rather than the music itself. I remember how frustrating it was when I was looking for something fast and aggressive, only to end up with some acoustic guitarist. No hate to acoustic guitarists, but that’s not what I wanted at the time!

So when we started this band, I wanted to make it clear that we’re a hardcore punk band. I didn’t want there to be any question about that. And it’s interesting because the times have changed. We’ve also become close with someone who was really active in the original queercore scene, and hearing their stories has shifted my perspective. Back then, it meant something different than it does now. I think for a queercore band to be taken seriously now, you can’t separate yourself from the larger scene. I’m not against queercore at all, but that’s where I’m coming from on the topic.

Cvlt Nation: Yeah, I think the Bandcamp and Spotify algorithms just don’t know what to do with terms like that. That was almost exactly my experience too—just a lot of solo acoustic stuff. Not even folk punk, just…

Noah: Singer-songwriter stuff.

Cvlt Nation: Exactly, which I love. I mean, sad girl music is my favorite. I listen to it when I’m not writing about a band. There’s plenty of it out there. I mean, Julien Baker is more hardcore than most hardcore musicians, honestly, but she wouldn’t label herself as queercore.

In another interview, you mentioned the bands that inspire your sound. You’re kind of basing your sound on the music that got you started, like Scorned, and I assume early Ceremony and Saber Tooth Zombie. On this most recent album, I hear a lot of what I would describe as power violence, especially in the song “Altar Call.” I also detect some noise rock influence, kind of like Pissed Jeans- style noise rock. So, I was hoping you could share who your musical influences are on this one. And if your favorite bands are all defunct, who do you like now?

Jeff: All Beat Up is the best band in the world, and they influence us a lot. They’re like our tour siblings. They’ve become family, and we love them. Their album that’s coming out—Mercy Thirst—is the best thing in the world!

Caleb: Yeah, I mean, that band is incredible and so inspiring. To me, it feels like they do everything that I want to do with Cockring. I have immense respect and love for what they do, and I think you can hear that inspiration on this record. I also drew a lot of influence from Greyhound when I was writing a couple of the riffs.

Jeff: But I do feel like for us as a band, we tour, we play shows, and then we fall in love with our friends and the bands we play with. We pull influences from that experience. Like, “Oh my God, that part of this band and this part of that band.” I feel like that’s what’s happening with bands like Greyhound and All Beat Up. We love those bands, and we kind of take different parts from them.

Noah: Yeah, I feel that too. I think originally when we were just jamming and writing our first songs, we focused on what bands we all liked in common, like Saber Tooth and Hoax. The more we’ve been active, the more our songwriting has evolved. I feel like we play a show or go to a show together, and when a band gets off stage, we’re like, “We have to do that!” It’s kind of funny, but it really comes from a place of celebrating the things we enjoy.

Jeff: Celebrating Northern California hardcore!

Caleb: Yeah, let’s go—Bay Area, Sacramento, let’s do it!

Noah: I like that you brought up the noise rock influence, too, because that’s maybe a more subconscious influence we’re all channeling. When we first started the band, and even now when I’m writing drum parts, I often copy and paste from early Bauhaus stuff. It has that very clockwork, rigid rhythm with lots of call-and-response kind of tom patterns.

Caleb: For sure. I think there are bands in Sacramento doing the noise rock thing that inspire us. _BLOUS3_ just released a record, and it’s really good. It reminds me of some of the stuff we were doing in the studio when we were recording this album. That band also shares members with Quinine, which is another very good and inspiring band.

Cvlt Nation: Beautiful. Well, I guess that covers everything I hoped to address and more. I’d love to ask my usual ending questions: What should people know about Altar Call?

Noah: This record acts as a time capsule of our journey as a band. It feels like a slideshow of all the amazing people we’ve met, the cool places we’ve been, and the things we’ve done. I just want to express a big thank you to everyone we’ve interacted with over the past few years.

Cvlt Nation: Is there anything else you wanted to say?

Jeff: Free Palestine.