Text Brad Feuerhelm

Photography Brad Feuerhelm & Janie Jones

via Dazed Digital

Death and photography have always been a close collaborator in my world and in 2011, I visited the Capuchin Catacombs for the first time. I became aware of the crypts in Palermo in 1998, when I started collecting vintage photography of death rites and customs in Europe. I had bought an old photograph of the crypt from the 1880s, which featured an astonishing cluster of bodies and coffins lining the cement walls of its subterranean arches and halls. Later, I would see further photographs by Peter Hujar and Sigmar Polke of its crypt residents.

On my first encounter, I was very timid and would only document the prepared mummies with a quick snap here and there with the aid of a concealed camera. Come 2014, I decided to return with an agenda to record the crypt properly after seeing Paul Koudounaris’ excellent photography book Empire of Death. Upon seeing his work and considering the history of photography in the crypts, I did the logical thing and had a Sicilian friend arrange for me and my team to gain access through the time-honoured tradition of almsgiving.

The sum I had to pay for one hour of time with the Palermo dead was 200 euros. Paying money to the crypt is a historical tradition and much in tune with alms given in the past, though I did feel the hourly rate for this sort of private visit was a bit stiff (so to speak). Our team arrived at 12.30pm when the crypt closed to the public. We were greeted by a very affable caretaker of the crypt, who wished us well and promptly vanished upon receiving our financial contribution, locking us in the crypt on our own.

Upon a cursory walkthrough I began questioning who was winning between the mirthful covenant between life and death. The crypt holds up to 8000 bodies in its holdings and dates back to the late 16th century, when the practice of embalming and display was reserved for the founding Capuchin monks themselves. It was not until later that women and tradesman were allowed in with a special chapel reserved for virgins (brides of Christ), children, and professionals.

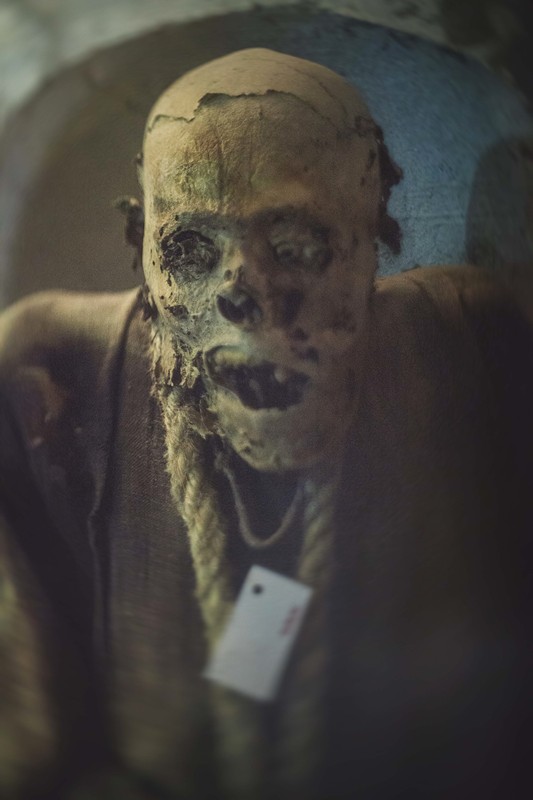

As we continued shooting, we walked through the crypt with a desire to paw and peel back the layers of flesh hanging haphazardly from various cheekbones, parchment-dry jaws and ocular sockets sliding towards the floor but held intact by time and the cool dry air. The lack of flies and sickly sweet decay of flesh were erasing the nausea that one would normally attribute to the necropsy that we were engaged with. It is only January, after all, and the distinct odour of death was palpably absent in the cool air.

The crypt itself acts as a schism between what we understand about our living tissue and its mortal decay. It is a giant sepulchre where Death glares back and in so doing, creates a soliloquy between the divide of the living and the dead. All of this would be tantamount to a similar divide between the respect one should give and the morbid feeling of being ensconced in death’s regard as it peers back from thousands of eye sockets. As Koudounaris points out in Empire of Death, these same eye sockets were left hollowed from their glass eyes during World War II – American GIs took the objects as souvenirs when they visited the site after its bombing.

Further on, one side chapel in particular has been opened for us and it is called the “straining room”. This room offers the greatest amount of trepidation for the team as we are greeted inside the small chamber by a pile of skulls, bones, and pieces of human flesh dried out like beef jerky. The remains are stacked on slats where, historically, the bodies are set to “drip” their internal organs and soft tissues into a bottomless pit for up to eight months before being washed in vinegar and having their cavities stuffed with hay to rebuild their corporeal architecture. In a corner of the chamber, the disused hay and flesh blend into what feels like an unholy mass of waxen adipose tissue and bone, feeling like a selection of missing studio props from Colonel Kurtz’s hut in Apocalypse Now. Odd reliquary fragments of children’s jawbones and ribs lie listlessly in a rusted coffee can next to the pile. I can’t help but think of these remnants as a leftover human trail mix: confusing, especially when you consider what respect for the dead is supposed to mean in a sacred place where atonement and silence, under the abject spectacle of death, are conflated with a heap of remains.

The crypt itself is architecturally designed to promote a sort of infinity of viewing, with long corridors stretching down three sides measuring perhaps forty to fifty yards, each of the longer stretches leading to the glass casket that contains Rosalia Lombardio, one of the last corpses to be admitted to the crypt. She is the Warholian Superstar of death, an incorruptible child of pristine lamentation. Master chemist and taxidermist Professor Alfredo Salafia embalmed Rosalia’s tiny corpse to near perfection in 1920. He had guarded his process of embalming in his manuscripts, which have recently been re-discovered, suggesting that Rosalia’s preparation was a near alchemical, multi-tiered process wherein the body was worked in several stages with blood and bodily fluid replaced by glycerin. This process differs greatly from the Catholic tradition of the incorruptible or saintly preserved bodies, where most of the tissue was covered in wax. The latter method makes it painfully obvious that the layers added were hiding the deteriorating flesh underneath, questioning further the ideas of the practice of the bodily preservation and its proximity to faith.

The hour spent documenting these sentinels of death was a confounding experience. It was one of slight trepidation, but overall fascination, to share such a close proximity to morbid Catholic reflections upon the body. The normal emotional rigors and mental paralysis often reserved for occupying such proximity to decay waned under the groaning heft of the job. We left exhausted from having to muster our focus and ability into one short hour surrounded by so much to see. The overall effect took its own tax from our breathing bodies, but we left ultimately with our own relics: totems and records taken back from lives that had passed decades ago… Documented for a new posterity on celluloid and memory card.