“After a decade of aesthetic outrages, four sides of what sounds like the tubular groaning of a galactic refrigerator just aren’t going to inflame the bourgeoisie (whoever they are) or repel his fans (since they’ll just shrug and wait for the next collection).”

August 14th, 1975: Rolling Stone blasts Lou Reed’s most controversial work, Metal Machine Music. In case you never experienced the thrill of this album, whose origin and creation is not to be discussed here, just consider that the description here above is quite effective. But there’s more to this thumbs down than just criticism of the hardly intelligible content of MMM. Known for his conceit as much as for his genius, Reed is also criticized for acting like a second-class rebel, making a lot of noise (sic.) for what the reviewer ultimately labels as a “wannabe-inflammatory” album.

So Reed was already old-fashioned in 1975? The reviewer quotes the John Cage – Merce Cunningham partnership as an eminent ancestor for MMM. Just to say: John Cage is the man behind the well-known 4’33’’, probably the most silent piece of music ever written. But we’d like to go more radically backwards in time than the Rolling Stone’s journalist did. More precisely, we’d like to go back to that epoch when “the tubular groaning of a galactic refrigerator” still had the actual power to inflame the bourgeoisie. And it had that power because it was really new. Therefore, we have to look back at Italian Futurism.

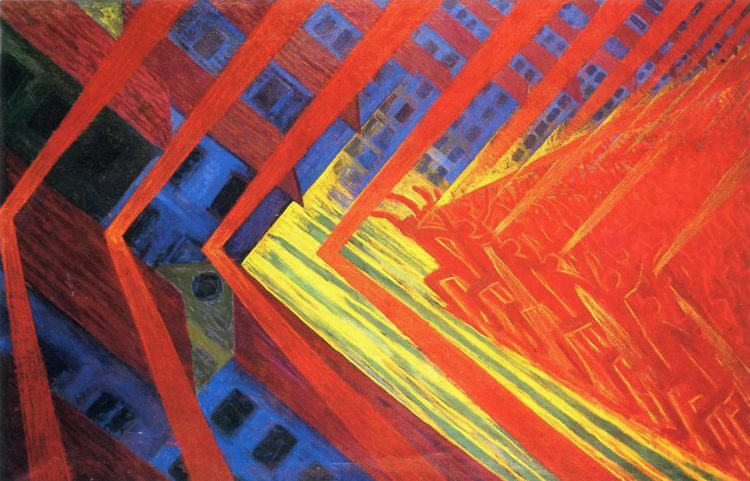

(Painting: Luigi Russolo, The Riot, 1911)

Milan, early 1910s. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti is collecting both praises and charges for his provocative opuses. Poet, playwright, all around outlandish guy, Marinetti published in 1909 the Futurist Manifesto, a statement of his philosophical conception of how art should have been created and understood from then on:

Literature has up to now magnified pensive immobility, ecstasy and slumber. We want to exalt movements of aggression, feverish sleeplessness, the double march, the perilous leap, the slap and the blow with the fist.

We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great tubes like serpents with explosive breath … a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

We want to sing the man at the wheel, the ideal axis of which crosses the earth, itself hurled along its orbit.

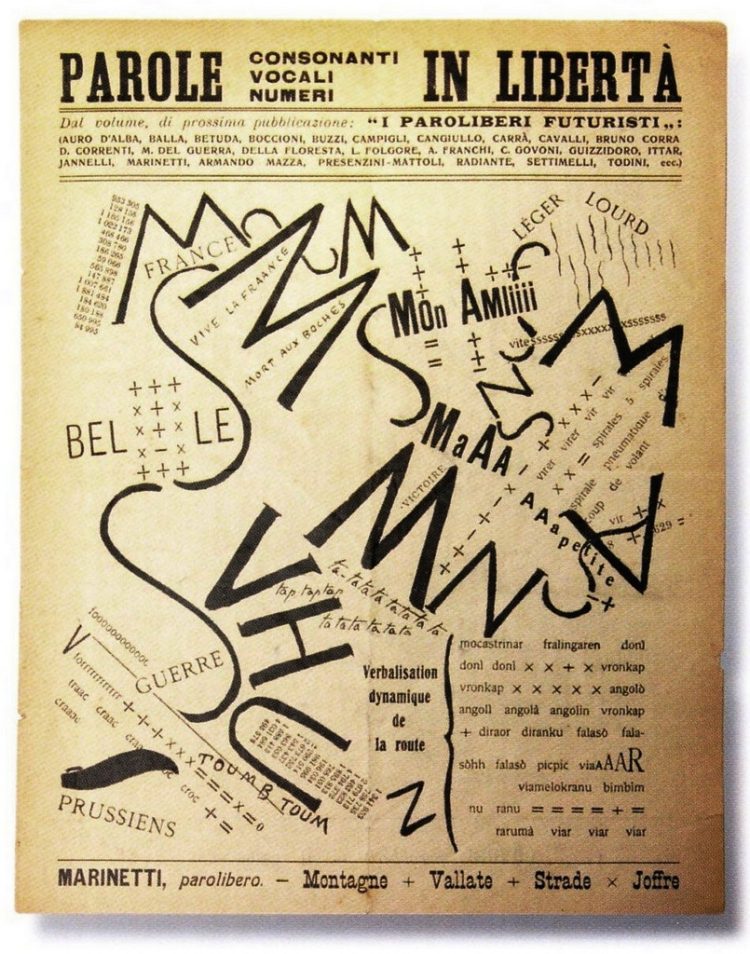

This point of view resulted into Marinetti’s so-called “parole in libertà,” a combined form of poetry and visual art. i.e, this example here below or this audio.

The work of Marinetti quickly inspired a passionate community of young artists, who gave birth to the Futurist movement. Beyond the charismatic figure of its leader, a handful of painters, poets, writers, designers, directors and even chefs began to stand out and mark new borders of artistic expression. Luigi Russolo was one of these budding innovators –and likely one of the most talented ones.

Born in 1885 near Venice, in the small town of Portogruaro, Russolo was the son of a clockmaker. He moved to Milan in his twenties and soon became one of the most valued young painters in the city. Curiously enough, at the times he was more famous than Umberto Boccioni and Carlo Carrà, whose works are now considered the highest peaks of representational Futurism.

Besides his inclination for painting, Russolo was an avid music lover since his very tender age. In his childhood, he used to spend hours and hours exercising on an ramshackle keyboard in his father’s shop. Therefore, it makes no surprise that when he decided to explore new incarnations of Futurism, music was his first choice. But what should Futurist music sound like, according also to Marinetti’s Manifesto?

The answer came in 1913 – a fundamental year in Russolo’s career and in the history of noise music. It was in early 1913, in fact, that Russolo’s Intonarumori (we can translate it as ’noise-tuners’) made their debut. The Intonarumori were experimental acoustic instruments designed to produce a specific noise or dissonant sound. Each instrument consisted in a wooden box containing a cardboard or metal speaker and a specific sound generator. According to the sound they produced, Intonarumori were more specifically named racklers, gurglers, rumblers, buzzers, bursters, hissers, howlers and rubbers. By varying string tensions inside the box, it was possible to actually tune the noise and control its volume.

Russolo composed several songs, serenades and actual orchestral pieces for his Intonarumori. Some of them involve also traditional instruments and even human voices:

It’s important to keep in mind that this seminal ‘noise music’ project was anything but fortuitous, and far from being a mere provocation. It leaned on a specific philosophical and artistic statement, which Russolo described in his pamphlet The Art Of Noise. In his visionary perspective, the so called “noise-music” was a physiological product of modern time, where silence is no more usual and human ear has grown more and more accustomed to machines and their “voices.”

This new way of conceiving music was quite sensational and brought his creator under the spotlight of avant-garde appreciators. Russolo died in 1947 having held concerts in Milan and Paris, where his Intonarumori were lately kept. And it was in Paris, during the bombing of the French capital in World War II, that most of his instruments were destroyed or stolen.

But not everything was lost.

Russolo’s sketch for his Intonarumori were preserved and in 2009, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Italian Futurism, a team of experts tried to reconstruct them. The experiment was made possible thanks to the cooperation between EMPAC, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, academic Luigi Chessa and luthier Keith Cary.

One test of these new Intonarumori has been held no less than by Mr. Mike Patton:

Ever since, many other copies of the original Intonarumori designed by Luigi Russolo have been made and some artist still compose music for this peculiar instrument (like Dutch musician Wessel Westerveld).

So…how about Machine Metal Music?