As a kid and burgeoning adolescent I spent almost every weekend for a period of years longer than I’m willing to admit at the local shopping centre. When you start to measure the passage of time by shopping mall additions and renovations you know you’re in trouble. It wasn’t just that I was dragged along every week by my shopaholic mother and enabling father, although that was certainly a key factor, but that I genuinely found some comfort in that palace of commerce and all its sterile, air-conned glory. It wasn’t even for any semblance of a family outing; apart from the obligatory lunch together during which I would dread being spotted by anyone I knew, it was the parting of the ways. My father would get a newspaper, plant himself somewhere and usually fall asleep until my mother was ready to go; my mother, a small unassuming woman who came into her own each week in that maze of products and price reductions. This was her element, and in it she became a woman on a mission, disappearing into a few hours of blissful, driven consumerism. As a budding consumer and capitalist flag bearer myself I would disappear into my own day of spending, or rather, a few minutes of spending, preceded by a day of anxious decision making. At that age I was dead in the midst of a self-induction into the wider world of music, graduating from what my older brother and friends turned me on to to what I discovered for myself via the internet, and each week my pocket money went straight into a new CD fraught with possibility and risk. Risk, because in those days of low bandwidth dial-up internet and my father’s fear that the smallest flaunting of anti-piracy laws would result in the Feds breaking down our front door within minutes, I could read about a ton of new music but I couldn’t listen to it, and so the weekly expedition to pick up a new album by somebody I’d never actually heard was loaded with anxiety and excitement, and you can believe the choice between two or more different CDs was not a light one. I would spend all day staring at album covers, track listings and spine labels, trying to imagine what was inside those mystical plastic-sealed jewel cases.

As a kid and burgeoning adolescent I spent almost every weekend for a period of years longer than I’m willing to admit at the local shopping centre. When you start to measure the passage of time by shopping mall additions and renovations you know you’re in trouble. It wasn’t just that I was dragged along every week by my shopaholic mother and enabling father, although that was certainly a key factor, but that I genuinely found some comfort in that palace of commerce and all its sterile, air-conned glory. It wasn’t even for any semblance of a family outing; apart from the obligatory lunch together during which I would dread being spotted by anyone I knew, it was the parting of the ways. My father would get a newspaper, plant himself somewhere and usually fall asleep until my mother was ready to go; my mother, a small unassuming woman who came into her own each week in that maze of products and price reductions. This was her element, and in it she became a woman on a mission, disappearing into a few hours of blissful, driven consumerism. As a budding consumer and capitalist flag bearer myself I would disappear into my own day of spending, or rather, a few minutes of spending, preceded by a day of anxious decision making. At that age I was dead in the midst of a self-induction into the wider world of music, graduating from what my older brother and friends turned me on to to what I discovered for myself via the internet, and each week my pocket money went straight into a new CD fraught with possibility and risk. Risk, because in those days of low bandwidth dial-up internet and my father’s fear that the smallest flaunting of anti-piracy laws would result in the Feds breaking down our front door within minutes, I could read about a ton of new music but I couldn’t listen to it, and so the weekly expedition to pick up a new album by somebody I’d never actually heard was loaded with anxiety and excitement, and you can believe the choice between two or more different CDs was not a light one. I would spend all day staring at album covers, track listings and spine labels, trying to imagine what was inside those mystical plastic-sealed jewel cases.

A lot of the time I took home clunkers. I grew accustomed to a state of post-purchase depression, berating myself with questions: Why did I just spend all this money on another album? Why did I spend all this money on something I’d never even heard before? What if it sucked? How much money would I have by now if I hadn’t gotten into this sick game?

And then when my purchase (often) did suck, an even greater depression. And then, about mid-week, the uplifting prospect of the next weekend’s vindication at the record store.

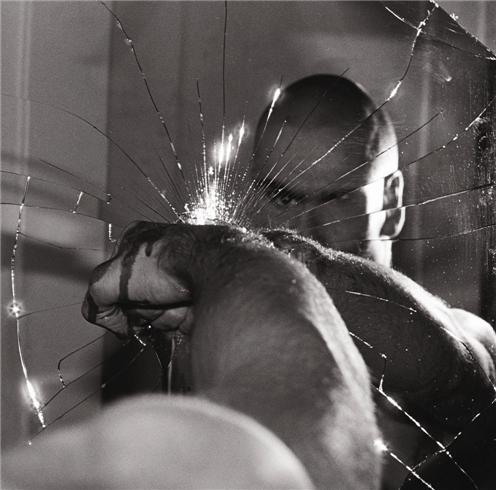

But then there were times when I hit on something great, and it was so much greater because of the risk and the ritual, and because there’s something about going into an album blind and finding something that really rips your heart out and burns it into that exact moment in time and space for the rest of your life (or youth). I remember everything about the first time I heard Damaged. I remember spending hours in the record store staring at that cover photo of Henry Rollins punching in a mirror, trying to imagine what the music inside sounded like.

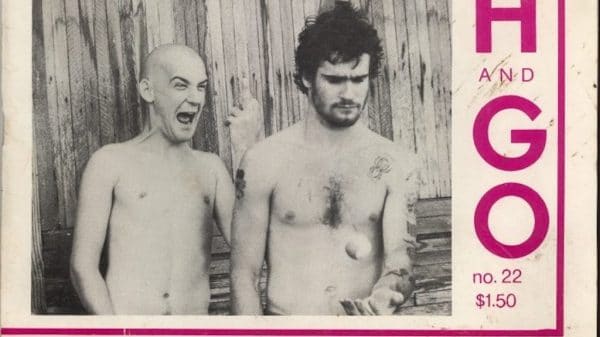

I’d never heard Black Flag before but those old familiar black bars were ingrained in my mind from every skateboard, tag and and home made shirt, and I’d skimmed over those nightmarish Pettibon cartoons of cocksucking nuns and knife wielding lunatics countless times before, before settling on something easier, something familiar. Now was the time to take the plunge, a thousand dirty punks sporting black bars couldn’t be wrong, could they? There was something there, some sort of secret club that wore those four bars as their gang sign, that I’d been noticing more and more since I’d started skateboarding and listening to a few tentative first punk records. I wanted in. I had no idea what those bars meant but for some reason I was drawn to them. I wanted to paint them on my skateboard and carve them into my desk at school and get them tattooed on my neck, but I knew I needed some Black Flag in my CD collection first or risk being branded a poseur.

But I was still hesitant. I had no idea what that jewel case held for me, and frankly, Black Flag scared the shit out of me. That photo of the exploding mirror didn’t help me at all, didn’t give any indication as to what to expect, although later of course I’d realise it summed the music up perfectly. Finally, the store clerk stacking CDs further down the aisle gave me the final push I needed with an offhand “that’s awesome” and a nod to what I held in my hands. Of course there was a member of that secret society literally metres away from me. It was like a real-world Project Mayhem.

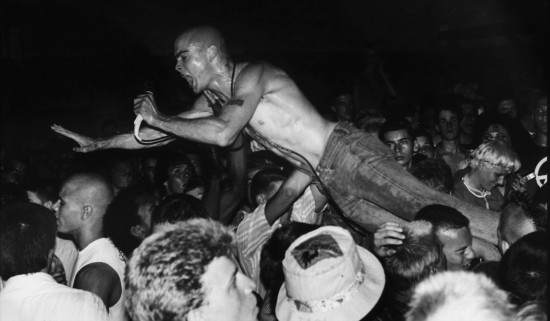

Home and headphoned, I felt the spirit of change enter my soul through battered microphones and chainsaw distortion. Piece of shit drums that sounded like the rattling windowpanes of my skull that Black Flag had come to kick in to forever fuck my brain and way of thinking. They were the sound of getting Damaged. They were the sound of the clean, precision played drums of my childhood’s favourite heavy metal and pop punk records being beaten into dust and noise by Punk Rock, calling me to Rise Above. They were the sound of skateboarding before and after it was an extreme sport. They were the animal moans of NWA actually Fucking The Police. They were the sound of the glass breaking on the illusions of suburban living.

And then with a squall of feedback Greg Ginn came in with a riff that was the sum of all the music I’d ever heard to that point turned inside out and beaten half to death in the street, only half to death so that you could still hears its screams and death throes through an amplifier that was a piece of shit before it was battered at every basement show in every city and thrown around the back of a van for the entire length of the United States, and I could hear the dirt and gravel and sweat and rage of every one of those states in the hiss and distortion that was calling me to Rise Above.

That hiss and distortion sounded closer to a human voice than whatever it was Henry Rollins threw at me next, the sound of sheet metal being shredded somehow formed into words, the sound of the mirror being shattered on the front cover, swallowed into his body to be spat back at me along with the shredded remains of his vocal cords, calling me to Rise Above.

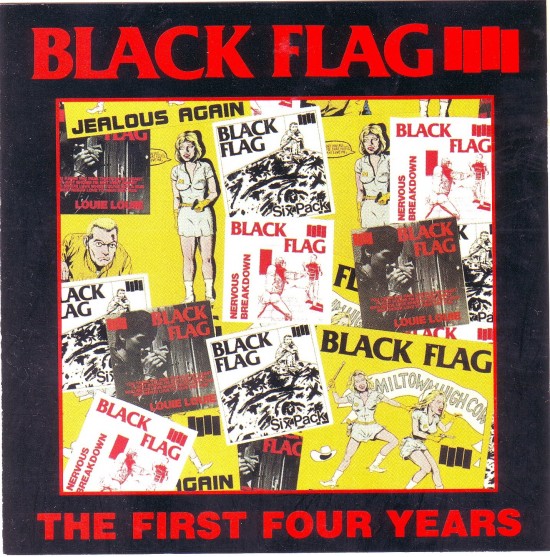

Calling me to Rise Above, calling me to Get In The Van. So what could I do? I was Damaged, and I still had fourteen and a half tracks to go. I finished that album and immediately listened to it five more times before going out to get everything else I could find by Black Flag and from this amazing new world of thrashed guitars and slashed vocal cords. I wanted The First Four Years because I’d heard it was even better, but I could never find it, and since I had to take home something by Black Flag on my next buying trip I opted for The Process Of Weeding Out instead.

That album blew my mind almost as much as Damaged had. Was this even the same band? There was no screaming. There were no vocals at all, for that matter. No one- and two-minute blasts of hardcore fury. Instead I was blindsided by an album of near ten-minute jazz instrumentals. Who the fuck was this band? I eventually also found a copy of Get In The Van, Henry Rollins’s tour diaries from the Black Flag years, in a local bookshop, and it cemented my total surrender to this new world I had just discovered, and the resolve that I had to do something with my life. Punk rock fed the fires of teenage possibility.

Weekly visits to the record store constituted my real teenage education, and I knew I was on to something really good when the store actually had to special order certain albums in for me. Those IMPORT stickers were like little seals of approval and promises of magic within. I did my research online and slowly worked my way across a virtual America, regional scene by regional scene, trying to visualise what these places looked like through clues I gleaned from lyric sheets and the sound of the guitars on a given record. I tried to decide where I would fit into these different worlds; was I more New York hardcore? D.C.? Boston? Dischord Records or Revelation Records? Faith or Void? Minor Threat or Youth of Today? Straight edge, left-wing, anarchist, vegan, Hare Krishna, youth crew, or skinhead?

Hardcore espoused the destruction of all other musical styles, but it really opened me up to more musical worlds than it tried to let on. Black Flag were the ultimate in hardcore mentality by giving the middle finger to the hardcore ethos itself and playing whatever kind of music they wanted to, like the metal of My War and the mind-bending jazz of The Process Of Weeding Out. Punk and hardcore weren’t about a sound but about the shedding of pretension. Whatever I wanted to do and whatever music I listened to was punk, as long as it was true.

In interviews I’d comb for influences and recommendations, bands would admit to guilty pleasures that became my guilty pleasures, then just my pleasures, and finally my all out loves. The jangling guitars, echoing drum machines and romantic synthesisers of New Wave were the aural antithesis of hardcore, but I found them just as earth shattering. The Cure, The Smiths, Joy Division, New Order. An older guy at my high school would hand me some new, mystical burned CD every morning and tell me “Listen to this”. That was all it took. The Velvet Underground & Nico, Psychocandy, and Loveless were among the treasures he bestowed upon me.

The Smiths even came to rival my Black Flag obsession. Henry Rollins and Morrissey sounded like polar opposites but they both spoke to the same electric currents of teenage life. The Smiths were one of the only bands that I had to own everything by, even the compilations and foreign versions that were basically the same albums, bar maybe one or two songs. I had Singles, Louder Than Bombs and The World Won’t Listen. The Queen Is Dead is probably still the most perfect forty minutes of music I’ve ever heard, and ‘I Know It’s Over’ maybe the single most beautiful song to grace these ears. I would listen to that song on repeat after numerous break-ups I felt should have affected me more, trying to force some emotion to justify the seemingly unnatural amount of love I had for the song. Every time I hear that album it takes me back to endless afternoons spent listening on repeat while tracing the progress of a spider across my bedroom ceiling and thinking about the normal kids outside in the sun and that girl who was definitely not inside listening to The Smiths and thinking about me.

I eventually did find Black Flag’s The First Four Years, and those early recordings were phenomenal, some of the best punk rock ever put to tape, but for me Black Flag is, was and forever will be Henry Rollins, and Damaged. Hearing that album for the first time was like finding the magic sunglasses from They Live that let you see the world the way it really was. Five minutes of Damaged and you started noticing sinister subliminal messages everywhere you looked, brainwash banners telling you to CONFORM, BUY, SUBMIT, REMAIN PASSIVE, DON’T QUESTION. Five minutes of Greg Ginn slaughtering his guitar and Henry Rollins slaughtering his throat and you started seeing aliens and evil overlords in every business suit and pair of spit shined shoes. Punk rock was an alchemical equation, an occult potion that stripped away the illusions of suburbia and the lies your teacher told you.

Teenage thrash and burn. Our band will be your life.

(taken from the book Electric Dreams)

http://danielvandenberg.bigcartel.com/product/electric-dreams