Interview by Jesse Feinman

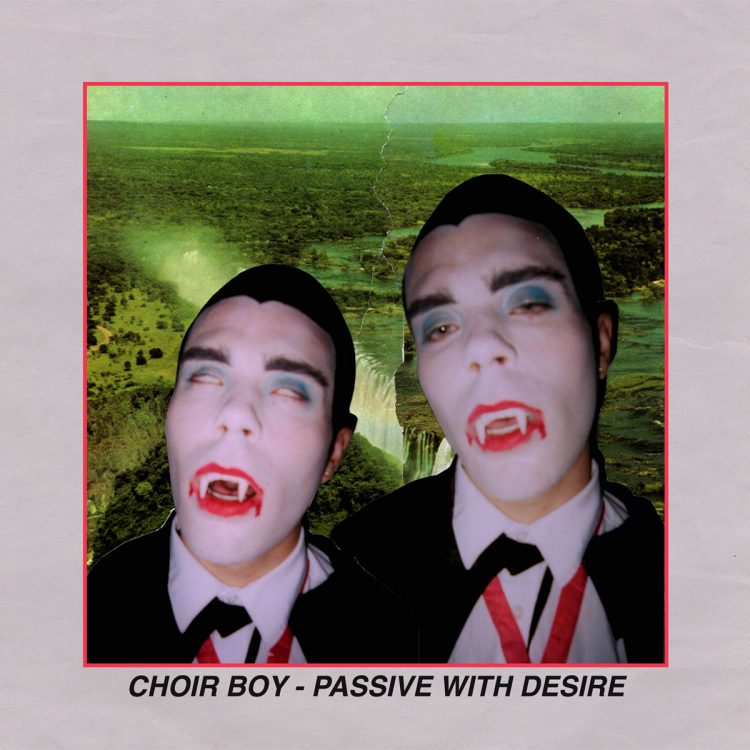

Choir Boy (Dais Records) is a synth-pop band that currently resides in Salt Lake City, Utah. They play a somber, introspective style of music not so far from the likes of New Order, The Wake, or even Bryan Ferry’s solo work. Their singer, Adam Klopp, is the brain-child and voice behind the project, penning gentle, dreamy, and romantic songs that exist as the perfect accompaniment to driving along the beach in the dark or walking home to your apartment.

I first met him in March, after they performed in Orlando, Florida to a sweaty room of fifty or so people. We exchanged a few words about the mutual friends we were surprised we had in Ohio, the place where he grew up, then gathered the band into the tour van to talk until close to two in the morning. I recorded the hour-long interview on my phone, then did nothing with it for months, as the band finished their tour with Soft Kill, then went on to hit the road again, this time supporting Cold Cave and Black Marble. I reunited with Adam for the Atlanta date of that tour, where the band performed in a much larger venue, playing somber hits as members of crowd slowly danced, either by themselves or with a close friend. That night I promised Adam, someone who I now think of as a friend, that I’d make sure to have this interview out into the world before much longer, and as such, here it is (in [mostly] its entirety):

Choir Boy resides in Salt Lake City, Utah, a part of the country not necessarily known for being prolific in regard to pop music. How has Salt Lake City affected the band, for better or for worse?

Chaz (Bass): I feel like Salt Lake may not be known for pop music, but there are surprisingly a lot of good pop acts that come from or are associated with here. I feel like our “place” may not actually affect our music as much as most people may think it does. I don’t know, the music that I write is sort of just the music that I write, wherever I am. But, that being said, I spent a lot of my upbringing bouncing back and forth between California, Arizona, and Utah, and Salt Lake has definitely been the most welcoming place. I immediately felt really welcomed in the scene and was given the opportunity to experiment with a lot of different styles and ideas.

Adam (Vocals, lyrics): Well, there’s a lot of pop music that comes out of Utah, it’s just mainstream pop. The Killers are Mormon, Imagine Dragons and Neon Trees are originally from Provo (even though they rep Las Vegas and Los Angeles) … There are a bunch of people from the Voice from Provo, too. That city is sort of like, a breeding ground for pop musicians, but not necessarily “cool” pop, if that makes any sense. I don’t know, Mormons are super ambitious, so if they want to do music of any kind, they want it to be the best, most successful version of that. We’re not necessarily trying to do the same kind of pop they are, not like Top-40 stuff, but a lot of themes in our songs do deal with Mormonism, as mine and Michael’s families are both super Mormon, and we’re all sort of navigating our lives post-faith. It’s strange, to have your trajectory completely abolished and need to start from scratch.

Utah sort of has a reputation of being an isolated state. With that in mind, and for you all personally, would you guys argue that it may exist as the opposite?

C: I’ve lived here for eight or nine years, and I’ve felt very welcomed, but there’s definitely a very unwelcoming vibe that I can’t really describe. The over-culture is, well, very stagnant, if that makes any sense.

Michael (Guitar): Most people who live in Salt Lake and Utah and participate in the music and art scene have this predisposition and eagerness to believe it’s an insular community. I know a lot music and art deal with the same themes of post-faith. What’s been cool about this tour (with Soft Kill) is that in each city, I’ve talked to somebody who’s like, “I understand that post-faith feeling,” even if it is pretty difficult to describe. Salt Lake, as a whole, does really have ties to everywhere else, though.

A: I think it’s kind of more welcoming and liberal than people may expect. Any time you have a hyper conservative or mono-culture that is the majority, the people who reject it tend to do so in a very extreme way. Mormonism is obviously super polarizing, so a lot of the people who leave it tend to do so in a very extreme form, whether it’s becoming militantly Vegan or Straight Edge or whatever. So as Salt Lake is becoming statistically less and less Mormon, even though the state is mostly conservative, the biggest city is pretty far from it.

Jeff (Keyboard): I moved to Salt Lake from Ohio not too long ago, and as I was getting ready to do so, all of my friends kind of joked around and were like, “Oh, so when are you gonna become Mormon?!” And, once I moved there, as I expected, I wasn’t really confronted with the religion that much, and all of the jokes from outsiders kind of just became really fucking annoying. It’s a far more liberal city than Columbus, Ohio, where I came from (laughs).

A: I moved to Salt Lake to go to BYU, the Mormon college. And admittedly, there is an intense scrutiny if you’re in the wrong circumstance. I was in a situation where people brutally scrutinized your behavior and morals, and your education was jeopardized to your commitment to the religion. There was a huge snitch culture. It’s really weird. If you’re trying to be a part of Mormonism, it’s definitely brutal. But, in Salt Lake, if you were never Mormon, or moved there not being one, it’d be pretty easy to never think about the religion.

Choir Boy’s music, lyrics, and even image are all laden with warm melancholy, nostalgia, and loss, all of which are very vulnerable themes. Are you ever concerned with being too vulnerable? As time passes, has it become easier for you to openly explore these personal moments in your life?

A: I think it becomes less fun to explore those themes the longer it goes (laughs). We talk about the stuff you mentioned in our songs, and it does feel a little revealing, but it’s important that it does, I think.

C: Art and music are places where I can work out things in a way I feel comfortable with, which is something I can’t always do in the aspects of my regular life. So being vulnerable in these instances, while scary, is somewhat empowering and feels more so like a positive, powerful thing. There’s never anything wrong with wanting to express your vulnerability. I think we’ve struck a great balance of being able to do that in a way that is touching to people.

Your debut LP is entitled “Passive with Desire.” Could you go into detail about the meaning of the title? As a whole, what do you feel this record is about?

A: I don’t think that has really gone on record, but Passive with Desire is a reference to a conversation with a friend of mine. They were talking about being passively suicidal, where you’re not actively trying to die, but you kind of, well, want to. And that sort of coincided with a phase I had in my life, where I was like fascinated with getting hit by trucks and tried, uh, a little bit too hard to get hit by them (laughs). I don’t know if this is too TMI, but I was a Mormon missionary for a short period in Tahiti. They wouldn’t let me go home, and that was when I really started thinking about getting hit by a car while riding my bike, wearing a nice, white clean suit. Splat (laughs). At the time, I didn’t really know it was a thing, but when I was talking to her I was like, “Yeah, whoa, I get that, I’ve been through that.” I don’t think all of that record is about wanting to die, necessarily, but a lot of it deals with not having the constitution to actively eliminate yourself from existence. I haven’t really talked about the record titles much in interviews, obviously, so it’s a little hard to articulate. In hindsight, I guess it feels pretty dramatic, but I was stuck, and didn’t see a way out, and thought it’d be a nice way to just get out.

The record closes with gentle, almost timid ballad-esque track called “Dark Room.” It doesn’t necessarily feel different from the record, but it is slower, softer, and simpler, than a majority of the record and it’s dolloped with brief moments of hope. Why did you choose to close the record with Dark Room? Is the Dark Room a physical place?

A: It is a place (laughs)! That song is about a mushroom trip, where I went to a hotdog party on mushrooms …

J: What’s a hot dog party? Like a literal hot dog party?

A: Yeah, we were eating hot dogs. It’s not a sexy thing (laughs). But I had done mushrooms before, and I thought it was such an amazing experience, so I took my leftover mushrooms and decided to take them again at the party. But, I had been really depressed and drinking a lot that weekend, so my follow up experience was really, well, depressing. I might have done them in sort of, I don’t know, the wrong way? It was still insightful, I sound like a hippie I know, but I did them in a way that made me feel kinda destructive, like the mushrooms rejected me.

So, first time, super insightful, second time, I was being reckless, and I went to a hot dog party fucked up on mushrooms. “Dark Room” refers to the room I was in when I saw all my friends like morph into these weird creatures, which made me feel insanely weird, so I abandoned ship and walked home. I was already working through so many weird things in my life, and I don’t know, it was just a lot. I know the song isn’t really psychedelic in the aesthetic sense, but lyrically and emotionally it is, considering I was literally on psychedelics (laughs). I guess, yeah, it is hopeful, like you said, because I was feeling messed up about my life, and doing those psychedelics made me face the problems that were awry. This isn’t maybe everyone’s experience, but I’m sure most people have felt like they’ve been forced to face something.

The A-Side of Passive is intentionally a little more synthy and poppy, whereas the B-Side is a little more organic and down-tempo. But, yeah, Dark Room was intentionally the closer because of the lyrical content and tone. It’s kind of a depressing record, and Dark Room is supposed to be some sort of closure for a depressing period of my life, even if it may not totally be over. At that point in time, even though it was so long ago, I was learning how to do a better job of finding a place in the universe.

Choir Boy’s newest release is a two-song single on Dais. How has it been working with them thus far? In addition, how do you feel your newest release compares to your previous work? Does it feel like a personal departure for you, or a natural continuation?

A: I think it’s a natural continuation. The songs are in line with themes and styles of the first record, but it doesn’t sound exactly the same. We’re fucking around with more disco stuff and dream-pop and whatever. The B-side is kind of like a dream-pop, waltz-y ballad. It’s the first song we’ve done that’s in three-four.

C: I feel like Dais is really incredible for giving us a lot of room to do what we want. They’re not asking us to basically write more songs off of Passive with Desire, because they are just like, fans of what we have done, and want to help support us do what we want to do, and so we can send them dreamier, slower songs, and it’s great. It feels less like a partnership and more like a friendship, where we mostly just want to eat breakfast together (laughs).

A: They’ve been really generous and come from a similar place as us. Gibby, who is the one we’ve interacted the most, used to be in a bunch of punk bands and toured and whatever, is just a believer in what we’re doing and the bands he puts out. It’s cool to feel the support from somebody that’s a curator we admire. It’s amazing to feel included in what he’s putting together. It’s equally amazing to just talk and hangout with him when we have the opportunity, too, like Chaz said. We totally trust them 100%, which I think is somewhat rare with record labels, right?

Outside of Choir Boy, you guys also play in a band called Human Leather (as well as others!) and create visual art. Why do you all personally feel the need to explore multiple mediums and presentations of music? Are there certain things you receive from your peripheral projects that you don’t get from Choir Boy?

C: I mean I’m in a ton of bands, and there’s still a ton of holes in my life (laughs). There’s just a ton of stuff I want to do. I don’t know how publicized the origins of Human Leather are, but the songs sort of came from the leftovers from the other bands we were doing (Choir Boy [which I temporarily quit], Fossil Arms, and Sculpture Club) that we wanted to mess around with. With Choir Boy, from a bass player’s perspective, I get to be a bit more melodic, creative and showy, so I can show my chops a little bit (laughs). I get to do the same thing with Fossil Arms, but I can sort of exude more energy, and with Sculpture Club, which I kind of view as a punk band, I can go more buck-wild and just let loose. It all comes from just being a fan of every aspect of music from the eras that I love and wanting to create and write things that honor that. Adam and I, surprisingly, have a lot of conflicting tastes, which translates into different writing styles and ideas. I feel like wanting to express yourself is a pretty natural thing, and for me, I guess I just use a bunch of different bands to do that in a bunch of different ways.

A: I think playing a different role in different bands can open a lot of different doors. You can learn how to do different things and learn from various people to try new arrangements and writing styles. Even if you’re playing with the same people under a different moniker, it still relieves a certain pressure to have to sound like “such and such.” Giving it a different name adherently gives it a different energy. Especially with punk music, you know, you’ll find that it’s often the same group of people in countless different bands, that do in fact sound different. Different names kind of give it a different energy. Jeff is the singer of this terrific band called 20XX. Michael has another band called Indigo Plateau. Chaz has all of the amazing bands he just mentioned. A lot of our projects exist in a similar realm of music, sure, but we all have different experiences with different configurations.

J: Michael and I both just joined Choir Boy for this tour. But outside of this, I have 20XX, yeah, and play in some “shitty” (Adam requested we removed the adjective from the article, Jeff insisted we did not) hardcore punk bands from Salt Lake. There’s an amazing label from Salt Lake called City of Dis that these two brothers run, which was actually one of the things that drew me here. They have a house called Dis House and do whatever the fuck they want which is really cool and mind-blowing. One of my biggest dreams was to be in a Dis band, and now I’m in, well four… I’m very happy about it, to say the least.

C: All of the City of Dis guys are great because they all come to our shows and we go to theirs. There’s no hierarchy or division, no “our bands can’t mix!” mentalities.

M: It’s nice and enlightening to explore different emotions through different creative voicings. It’s something you gain from playing in different projects, working with various people who have unique approaches to life and emotions.

Lastly, any exciting plans for the future? What, if anything, has helped to keep you happy and hopeful?

A: Keep writing and do an LP soon as possible. Have no clue when the ETA is, but record and release as soon as possible. We have an exciting tour along the way (which turned out to be alongside Cold Cave and Black Marble).

C: I feel good playing on stage every night with the people who are in the band right now. I love it so much. It’s a place, where no matter how frustrated or annoyed we are with one another, in which we can find 30 or so minutes of pure, blissful joy. It’s a feeling that I want to chase. For maybe the rest of my life. We have a lot of writing to do, and we want to do it as soon as we possibly can.