As evidenced by the legend of John Henry and his heroic battle against the steam-powered drilling machine, humankind has harbored complex feelings toward their own technological innovations since at least the industrial revolution. There is an anxiety that, someday, much like the son who grows to best his father in a good-natured boxing match, our intellectual progeny will grow to be too powerful for us to control, and in a global climate that embraces competition as a motivator for advancement, it seems inevitable that our inventions will gain sentience, that they will gain self-reliance, that they will no longer need the weak meat-sacks who bore them into a world grown cold.

This idea of a singularity, of a time when our machines will outgrow us, has driven science-fiction since at least Isaac Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics, which point at the likelihood that robots powerful enough to help us will also be powerful enough to harm us, and that counting on their loyalty is naïve. Or dangerous.

The same potential for danger that drove Asimov’s creativity now drives Tucson industrial heavyweights Realize. Just like Einstürzende Neubauten and Laibach in the early days of home computers, just like Ministry at the dawn of the Internet, the desert mechs in Realize have their fingers on the speeding heart of what may eventually be called the Zoom Generation. If anyone was skeptical about our dependence on the digital world to carry on our lives, the last six months of social distance have shown that life as we know it would cease without the devices that are meant to be our accessories but may in fact be our caretakers. The time is ripe for musicians such as the three scene-veterans in Realize to embrace a technology which one day may destroy us, and synchronize with it.

It’s time for a new Industrial Revolution.

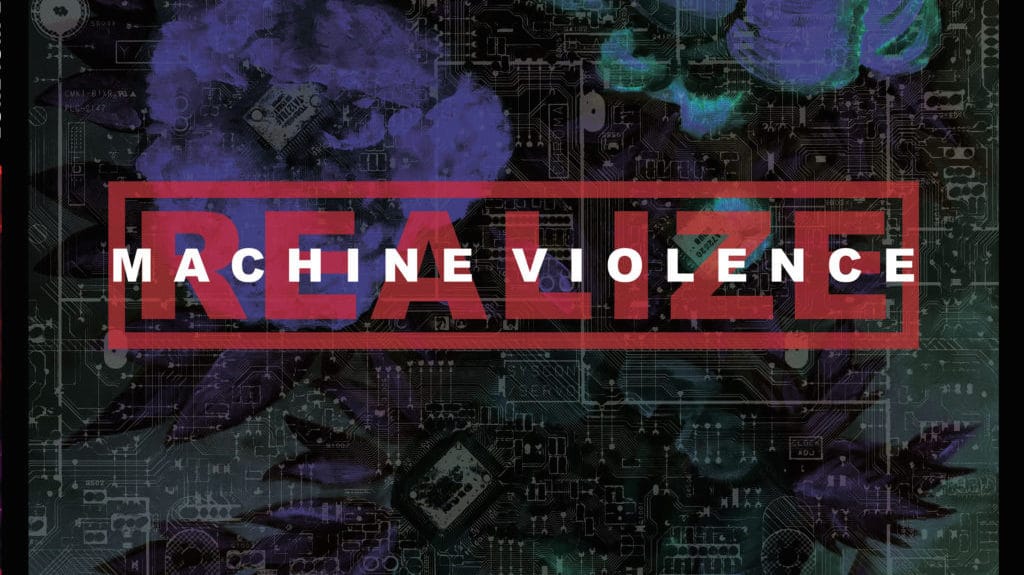

In 2018, Kyle Kennedy of Arizona powerviolence titans Sex Prisoner released the first Realize album, Demolition, on To Live A Lie and Regurgitated Semen Records. The album, recorded and mixed by Ryan Bram and mastered by Brad Boatright, immediately made the world of industrial metal buzz. Sex Prisoner–whose vocalist, Kevin Kennedy, contributes guest vocals to Machine Violence–began as a three-piece with bass as the only stringed instrument, and Kennedy’s time making driving, innovative riffs in that band prepared him brilliantly to channel early Justin Broadrick projects with the thicker, bass-heavy tone of his more recent, 8-string-equipped Godflesh releases. Now, building on the hammer-on-anvil fury of his debut, Kyle Kennedy has employed guitar giants Matt Underwood (Sex Prisoner) and Matt Mutterperl (North, Languish) to help build the sophomore colossus that is Machine Violence.

Without losing any of the heft that made the aptly named Demolition such a wrecking ball, Machine Violence adds color. As if there is now a new ghost in the machine, there is something more organic, more human about this album. While still industrial metal in league with the best of Nailbomb, Front Line Assembly, Nine Inch Nails, Godflesh, Ministry, and later My Life With The Thrill Kill Kult, Machine Violence innovates, making great use of Mutterperl’s and Underwood’s talents and exposing Kennedy’s raw vocals more. The album is warmer, and this warmth extends to its drum programming.

While Demolition was clearly driven by a drum machine, hearkening not only to early industrial but also to grindcore acts like Agoraphobic Nosebleed and Enemy Soil, Kennedy’s command of his emulators has grown–as has the technology, presumably–and when the full band is in the mix, the casual listener would be excused for thinking that one of Arizona’s stalwart drummers–Matt Arrebollo, Gilbert Flores, or Zack Hansen, for example–might be on the throne. Further humanizing the mechanical assault of the songs, on most Machine Violence tracks, Kennedy utilizes a cleaner approach to his vocals, allowing more of his youthful, hardcore-hardened voice to filter through with fewer effects, creating an image of Mike Ferraro or Joe Denunzio in a cockpit of a BattleTech, commanding a fleet of mech-warriors through an alien apocalypse.

An atomic clock powered by a human heart, Machine Violence fuses man and machine. Favoring computerized amps and effects processors over their usual stacks, Kennedy and the Matts leaned into the increasingly digital world of recording, yet the songs sound raw, real, meaty. Beginning with the uneasy palpitations of synthesized drums before giving way to a dirge-like three-guitar attack, album opener “Alone Against Flames” captures the anxiety of living in a civilization on the precipice, a society on an irreversible path to its own destruction. “My lungs feel like dust turning black. I feel it burn. NO PEACE.” Kennedy’s words remind one of the ashen world of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, a world that seems more real with every day’s news cycle’s ecosystem-ending wildfires.

The album’s second track and third single, “Melted Base” utilizes a buzzsaw bass tone that recalls the grunge-sludge of Fudge Tunnel and echoed barks that invoke shorter-lived Jourgensen projects like Revolting Cocks and 1000 Homo DJs as much as Psalm 69. “Ghost in the Void” is an overwhelming wash of tone that combines the proto-djent of Fear Factory with the dissonant upper-fret accenting of early self-titled-era Korn. The song is an unstoppable wall, ever advancing, ever strengthening. One feels crushed under its weight, as Kennedy’s voice breaks through the din: “Sometimes I feel like I’m a ghost.”

“Long Stare” is a game of cat and mouse. From the opening speaking-on-condition-of-anonymity vocals, the song is all about tension and release. A perfect track to follow the army of sound that is “Ghost in the Void,” “Long Stare” plays with the listener’s expectations, most notably through the use of extended pauses, held together by the thread of a singular, synthetic hi-hat before erupting into a battery of guitars that sound like submachine-gunner stomping on bodies in a frenetic search for their lost battalion.

“Disappear,” one of the album’s first singles, combines the ambiance of an after-hours nature special with a full-gore World War II documentary. The Panzer fire of heavy bass, guitar, and drums is made more menacing by the haunting high pitches that would accompany a scene of a spider catching, envenomating, and eating a lizard thrice its size. “Simulated World Down” is a mid-tempo soundscape of a city pulverized under a gradual but inescapable avalanche of black debris, natural and man-made. Both that song and “Slag Pile,” another early single, exhibit anxiety, angst, and rage in equal measure, capturing the man-meets-machine experimentation and edge of early Godflesh, Meathook Seed, and Nailbomb.

In a creative turn as inspiring as it is surprising, Machine Violence ends with “Heavy Legs in the Mansion,” an arpeggiated acoustic piece whose poignance and emotional delicacy contrast radiantly with the armageddon that fell before it in songs like “Hypermech” and “Gateway Trial.” After nine tracks that signal the demise of humankind at the hands of its own creations, “Heavy Legs in the Mansion” is a love-song to hope. Like the sun rising to cast its rays on the sole green shoot sprouting from the rubble of a fallen age, it is the sound of a world recovering from the humans who once inhabited it.

One hears a voice, distant, say, “I feel like time is turning back, again. Old self, are you there? I don’t feel like I know this place at all, anymore.”

Photo by Kiley Kennedy.

Kyle Kennedy was kind enough to share some thoughts on Realize’s amazing new LP.

Sophomore releases are notoriously daunting creatively. Adding to that, Realize signed with Relapse this year. Did you approach writing and recording differently knowing that this release is following the success of Demolition and that you will have a larger platform?

Yeah, sophomore releases can be tricky — they’re an opportunity for bands to progress their sound, though sometimes you can get stuck and aren’t able to advance or offer anything new/interesting. Many of the song ideas I came up with directly after recording Demolition were pretty lame. It probably wasn’t until six months or so after Demolition was finished that some ideas began to stick. Stepping away and coming back with a fresh perspective can help with new releases. For the second release, I originally wanted to start small and release a 3-4 song EP, but as the writing process progressed, we figured that an LP was doable, and probably a better vehicle for a second release. We actually approached Relapse about releasing Machine Violence after everything with the record had been recorded and mastered, so the platform and potential visibility weren’t a major consideration during the writing process. We wanted to write a dynamic record as best as we could, and revive some of the industrial metal sounds from the late ’80s and early/mid ’90s, while also putting our own spin on it.

Who were some of the strongest influences on this record, in terms of music and lyrical themes?

Our biggest influences are Godflesh, Ministry, and Nailbomb. Godflesh songs are incredibly interesting to me, and I love the energy and riffs of Ministry and Nailbomb. The album also incorporates some hardcore/metalcore inspired song structure, riffs, transitions, and vocal patterns. We also took inspiration from Black Sabbath and Korn, especially with respect to some drumming and lead/noise guitar harmonizing. When people first listen to Machine Violence, our inspiration from Godflesh will be pretty clear. In terms of our own mark, I would say that our songs are less repetitive and droning than a lot of industrial tends to be (some people would argue that that’s a defining feature of industrial though haha). An aspect of grind and powerviolence that I enjoy is the non-cyclical music form of songs. I had that ethos when approaching songwriting for Machine Violence. With that said, there are repeating parts, we just tried to mix it up in terms of musical form. We also have a song that is only acoustic guitar, synth, and vocals, which is a bit unusual haha.

Machine Violence doesn’t have an overarching theme, but instead touches on several lyrical concepts, though they aren’t necessarily cohesive or in chronological order. Some songs are about the idea that we exist in a simulation and everything we know/experience is part of that simulation, and what happens if the mind is released from the simulation, kind of like the Allegory of the Cave. Other songs are about altered states of mind, in which the mind exists outside of simulation, however, it’s perception of events is so far removed from reality (from brainwashing, isolation, etc.) that it effectively perceives itself to be in a simulated state. Other songs are more human and are about anxiety and fear. I’m an avid Sci-Fi reader, and many of the ideas originate from various books I’ve been into. The literary ideas and music go hand in hand. I probably wouldn’t be inspired to write harsh and bleak music without contemplating uncomfortable topics

How has the addition of Matt Mutterperl and Matt Underwood affected the writing process? How has it affected the sound?

Realize started off as a solo composition project. I’ve always been drawn to industrial music; it’s very aggressive and sterile/bleak, though sonically it doesn’t have clear boundaries, which can be good for experimenting. After I recorded Demolition, I wanted to play it live, so I approached both Matts to play live guitar. Looking back, I was too isolated when writing Demolition. After we played a few shows, I wanted to write new material and have the Matts provide feedback and contribute. The Matts were great in that I could bounce ideas off them, and they would offer an outside, critical perspective that would challenge my thought process. I think that people subconsciously (or consciously) approach the creative process differently when they know someone else will be critically consuming it. Also, when we started writing Machine Violence, my drum machine programming skills were more advanced compared to when I was just starting out writing Demolition. I also wanted the vocals to have more variation throughout the record, notably with respect to echo effects, and the low demon effect.

The three members’ other projects are sonically very different from Realize. Has it been challenging to adapt to a different genre? Are the songs written for Realize specifically from the beginning, or do they start out as creative “germs” that are purposed for Realize somewhere in their development?

Realize and our other bands are distinct enough so that they don’t interfere with each other creatively. I originally started Realize as a way to explore another genre, and also to challenge myself to change up my writing style. Given that, I’ve been intent on keeping the bands separate. I was (and still am) an avid listener of industrial music, so the style wasn’t completely foreign to me when I started the band, which helps to adapt to a new style. All of our songs so far have started off as songs for Realize; there’s been no cross-pollination.

Industrial seems to be experiencing a rebirth, with bands like Realize, Street Sects, Uniform, and Author & Punisher being some of the most well-known acts in the genre today. Do you have any thoughts on what has caused the seemingly sudden rise in its popularity?

That’s a good question; this all is speculation and conjecture, but I feel like there are a few things that have caused a rise in new industrial acts. People and society are seemingly becoming more isolated. While industrial music doesn’t have clear boundaries, it is rooted in electronic music. Generally speaking, since people are spending more time alone, musicians are creating electronic music independently, or with a partner, and may not be collaborating as much with others, especially as compared to jamming with a full band. This is not necessarily specific to industrial, but perhaps a partial explanation to the rise in electronic music in general.

The draw to industrial specifically is likely due to the excellent existing music within the genre, and the fact that Industrial music is typically very bleak, sterile, and aggressive, which may be a reflection of people’s views on life and society. Industrial is also a great genre to experiment with which allows musicians a challenge and opportunity to create new and unique sounds. Overall, it’s just a badass genre haha.

What are some musical acts that excite you right now?

There’s a new industrial band called Black Magnet that just released a great new album (Hallucination Scene); I hear influences from Godflesh, Ministry, NIN, and Skinny Puppy. I’m also into Fange, a heavy and intense band from France that has industrial influences; they’ve recently released a couple of really cool albums. I’m also really into Kruelty, a Japanese beatdown/death metal band; their recent album (A Dying Truth) is extremely hard and has really interesting riffs — there’s not a bad song on it.

What should people know about Realize and Machine Violence?

We’re excited to play shows whenever society opens up again. We want to try to do a run on the East coast and a few West coast shows. We won’t have a drummer, we’ll be using our drum machine live. Also, my wife painted the paintings on the front and back cover of Machine Violence. My brother also does guest vocals on a few songs, so Machine Violence has some nice contributions from my family.

Machine Violence is Realize’s first release through Relapse Records.

Recorded and mixed by Ryan Bram at Homewrecker Studios.

Mastered by Brad Boatright at Audiosiege.

Album art, photos, and layout by Kiley Kennedy.